Tino Sehgal

June 28 – August 8, 2015

Martin-Gropius-Bau Berlin

Niederkirchnerstraße 7, 10963 Berlin

Exhibiting at Martin-Gropius-Bau is a challenge. The majesty of the renaissance interior can easily distract from the viewing experience of the art. This summer, however, the ground floor atrium has become the stage for Tino Sehgal’s work, which does not suffer from the surrounding grandeur, by virtue of being theatrical, immaterial, and adaptable to its setting.

Martin-Gropius-Bau, Lichthof

The five works that are featured in the exhibit are not objects, but choreographed events performed by 80 actors who work in shifts. As the press release points out, Sehgal makes a point in distinguishing his work from performance art, by referring to his pieces as situations, social sculptures, or interaction architecture. In this exhibit, the spectator is not as involved in the performance as in other works of the artist, where at times it is not immediately clear whether one is witness to a staged performance or to a real life event. Here, with no other exhibits around, there is little ambiguity. The performers are clearly performing and the museum-goers are clearly there to watch them.

Ann Lee (2011) presents a little girl that tells the story of how she started out as a manga character named Ann Lee, but wanted to become 4-dimensional. She asks the audience: “Would you rather be too busy or not busy enough?” There are various responses, but Ann Lee invariably replies: “Why do you say that?” “Hmm.” “Interesting.” and then continues her story. This character would certainly fail the Turing test, but she might get people to briefly think about the way they live their lives.

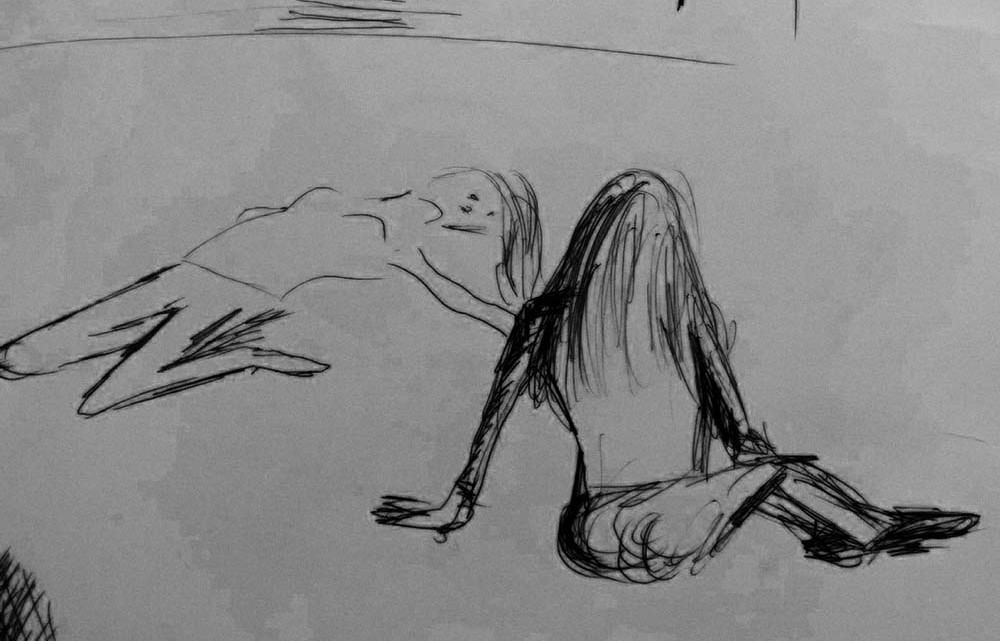

Johanna Thompson. Visual Notes for “The Kiss,” by Tino Sehgal (2007). Courtesy the author, 2015.

The Kiss (2007) has a couple reenact famous kissing scenes from art history, bringing to life sculptures and paintings ranging from Rodin to Koons. Interestingly, this work has less impact when performed in the atrium than in the side chamber, where it is enacted in absolute darkness. There, the museum visitors enter carefully, tentatively, until their eyes get accustomed to the dark, and the shapes of others become visible. In this setting of heightened attention, one suddenly becomes aware of a presumably naked couple making out, changing poses in the dark. The art history lesson is lost without lighting, but the experience of witnessing an unexpected secret shrouded in darkness more than compensates for it.

In another pitch-black room, we hear an acapella choir in the dark. Again, in This Variation (2012), the experience of being so vulnerable and unsure who and what is around you heightens the sensation. When the acapella choir rotates into the atrium their song and dance turn into a show that feels a bit like a plotless musical that seeks to cover topics ranging from labor rights to philosophy and the general state of society.

“Welcome to this situation” is the greeting extended to the visitors by a group of people who, in The Situation (2007), are discussing ancient quotes that may or may not be relevant now. The pattern by which they switch positions (while moving backwards) makes the transitions look like a dance. It is unclear if the audience is invited to participate. No one does, as contributing to the conversation feels like the equivalent of touching the art object.

Ausstellung Tino Sehgal, Interpreten, Juni 2015 © Mathias Völzke

Sehgal catapulted to celebrity in just 10 years, taking the international art world by storm. He has become the guru of interactive performance art, a form that he will not allow to be documented nor advertised. Yet, his work is sold for enormous sums, by verbal contract only. Whether the refusal to document or advertise makes the art any more profound is debatable, but it certainly helped raise curiosity and elevate the artist to cult status.

Sehgal is not the first artist to use the museum as a venue for performances, nor the first to delegate performing to performers, nor the first to involve the audience. These methods have been explored in performance art and fluxus happenings since the 1960s, but his work is clearly distinct from this history. His show is a crowd-pleaser and an entertaining mix of choreography and interactive theater, but it also raises questions about what makes an artist with such a seemingly challenging and unconventional approach to art so instantly popular.

Of course, the way for time-based and immaterial art has been paved by the avant-garde of the last century, but that is not the only explanation for his success. When comparing Sehgal’s work to other types of immaterial art, there are fundamental differences. For one thing, unlike performance art, happenings and conceptual art, his work seems informed more by choreography and theater than the history of visual art, which is no surprise, given that his education is in choreography and economics rather than fine arts. Tino Sehgal himself acknowledges the influence the Berlin theater culture of the ‘90s has had on his work. Also, while performance art was born out of protest against established structures and the desire to break away from the old and venture into the unknown, Sehgal does not rebel, but instead uses the infrastructure of the establishment in which his work lives. The gallery venue, the art market, and the museum-goers are all vital to the operation of his works.

Ausstellung Tino Sehgal, Interpreten, Juni 2015 © Mathias Völzke

He refers to his art as “situations,” bringing to mind the concepts of the Situationist movement, which is rooted in Marxist Theory and anti-authoritarian ideas. The Situationists believed that in a Society of the Spectacle (Guy Debord, 1968), where representation and consumerism have replaced actual living, art should no longer consist of objects but rather of the creation of situations in order to return to unmediated living, to living life directly. The press release for Sehgal’s exhibit hails his art as radical and new, due to its absence of objects and its performative nature, but does not acknowledge those who have come before him. What is truly new about his work is how, under this guise of radicalism, Tino Sehgal has created situations that are marketable and profitable commodities, easy to consume, and do not oppose or criticize an art world based on capitalism, but instead fortify those structures.

His eponymous show at Martin-Gropius-Bau is beyond a doubt entertaining and spectacular, but it is neither radical nor subversive. These situations that entertain the crowds and are sold for substantial profit would make Guy Debord turn in his grave. On the surface, the lack of objects in combination with politically infused content make his work look novel and insurgent. But Sehgal is only formally employing devices of the radical practice of the avant-garde, and he is using them with very different intentions. His brand of “immaterial art” is not about the dematerialization sought by those who coined the idea and wanted to oppose the creation of commodities in a capitalist system. With his version of immaterialism, he has managed to create a new type of commodity that is highly sought after in the art market and, by doing so, has apparently filled a void.

And this is where we find the real merit of Sehgal’s works. He has truly brought innovation to contemporary art by successfully exhibiting and capitalizing on the non-commodity, and this is where he deserves credit.

Ausstellung Tino Sehgal, Juni 2015 Tino Sehgal © Mathias Völzke