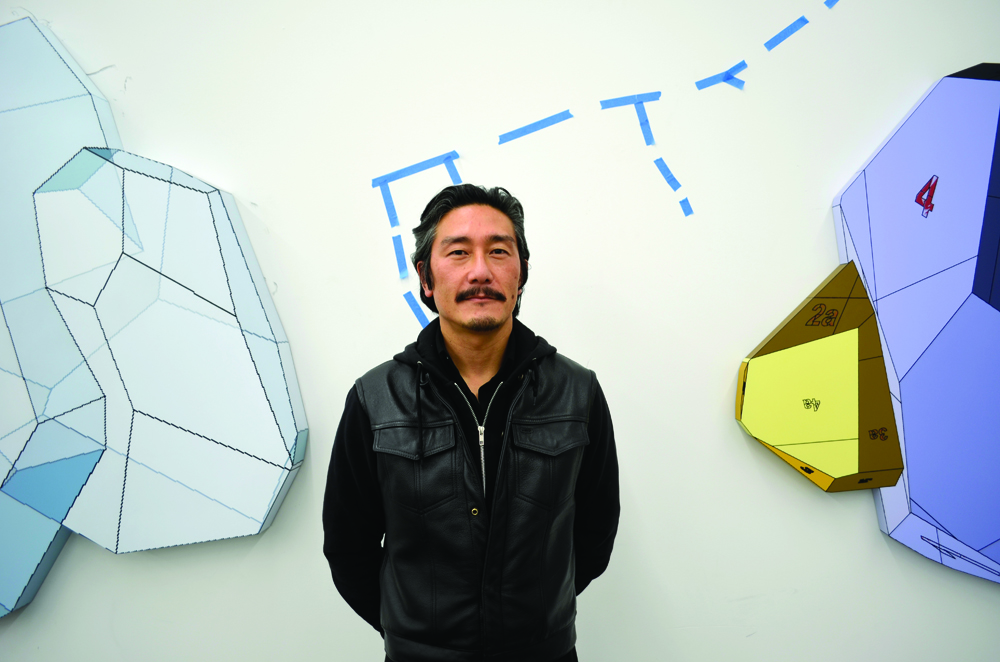

Michael Joo is a rare artist who’s practice intersects multiple disciplines from both the core and periphery of art history’s framework. His body of work is often difficult to sum up due to its vastness. For the past two years, Michael has been a mentor to me, and has opened the door to artistic discourse during our many studio visits. Today we will be talking about his work.

Interview by: Korakrit Arunanondchai

So when you entered the Yale MFA program – you knew you wanted to be an artist for a living. When did you start there again?

I started in ’89.

I saw “The Tripod”.

Oh yeah, way back. That was undergraduate.

And “The Dog”.

Yeah, I was doing a lot of things with prosthetics and [calories] back then.

So who were you looking at? I just feel like back then people were really confused? Because your work is very scientific, you know?

I was looking at artists like Hans Haacke, or Robert Rauschenberg who was doing collaborations with Billy Klüver in Sweden and Experiments in Art and Technology; 1960’s Haacke works involving environmental concerns, water purification pieces, which are amazing. I was also looking at Barry Le Va, and Oyvind Fahlstrom, mostly his paintings in the 60s, some of his installations… Jana Sterbak, Rebecca Horn.

Let’s talk about your art practices because from then to now, your body of work is just so wide. I feel like you have four or five things developing at once and they just kind of get pushed forward. Let’s start with the installation “Yellow, Yellower, Yellowest”. The piece contains three beakers of yellow liquid, labeled as the urine of Ghengis Khan, Benedict Arnold and you – the Artist.

One of the themes in my work I’m concerned with is the notion of transformation, and how we perceive that transformation; in a very loose way it relates to our preconceptions about spirituality, the S-word… terms like that—it’s like the impossibility of the idea of setting out to be subversive. As soon as you utter the word, it’s gone. In “Yellow, Yellower, Yellowest,” I was interested in playing with the meaning of the color yellow. I had taken color theory classes that had traumatized me. The repetition of trying to reproduce color… and so I worked with this color yellow for awhile and tried to extend some of its meaning. In this piece I was just basically asking, could you get to the root or essence of that color in a more immediate way? So I pissed in three different beakers at three different times of the day. I thought that would be my scientific control, the time of day, and then I let it evaporate to crystals to see what happened to the color. The samples that they denote were listed as Genghis Khan, Benedict Arnold and Michael Joo — in that order. I thought that it could be seen as another way of determining through language how the color yellow was assigned to identities. The tray that they sat on, engraved, Yellow, Yellower and Yellowest, to throw in the idea of value, or hierarchy. It smelled very bad.

Michael Joo, “Yellow, Yellower, Yellowest”. 1992. Engraved aluminum shelf, glass beakers, urine, preservative, vinyl. 156 x 96 x 48 inches. Photograph by Tim Lloyd. Courtesy of the artist.

This was left in the gallery?

It was just left to evaporate over time.

It’s interesting, like coming into a laboratory—starting with something pretty out there, like spirituality, then incorporating a poetic internal thinking, and in the end the final product. I’d actually like to talk about “Salt Transfer Cycle”. That seems like a really important piece.

There’s a lot to be read in between the lines of information. Scientific language can be precise and exact, and reek of authority, but can also be extended to comical proportions with, say, ingredient listings. I was really obsessed with the concrete poetry, for instance, on the back of a candy bar – something with all of its artificial ingredients, none of which you really knew, but was something named, something verifiable. If you’re standing in line at the checkout counter reading ingredient and caloric information, it could be seen as a tiny moment of alternate reality – when you read all this information and you try to project what you’re going to do with all that stuff, what it means to you, there’s a little hidden meaning inside of that moment, too.

It goes kind of unnoticed.

Yeah, I think we get completely conditioned to ignore that part of day-to-day information upload.

Do you think this is how science and information works, the way it parallels modernism, as a metaphor for truth? These are all the ingredients, this is truth, but in the end it’s still not understood. Even in truth – it’s a lie, it misrepresents itself as something accessible or supposedly useful: the label.

Definitely, but it seems authoritative. You don’t always know whether science and “information” are one and the same. But science is used typically as the language of authority, coated in specialized knowledge and fields of study. It has naming in its core, identifying and naming.

With “Salt Transfer Cycle”, you’re talking about performance. As an Asian man, using yourself within the performance draws questions of identity and how it can be perceived as “ready-made.”

Yeah, that’s a great point. I like you saying that, that an identity could be “ready-made”, that identity is already made based on physical appearance. This long-haired Asian guy.

Because always, it’s weird, in the Western World an Asian man using his body to do a performance is different—there’s a difference in that, the cultural and political baggage that comes with it.

That was definitely a concern of mine, confusing that identity and its complexities. Playing with assumptions of essentialism.

Michael Joo,“Headless”, 2000. Urethane foam, pigment, vinyl plastic, styrene plastic, urethane plastic, stainless steel wire, neodymium magnets, 66 x 336 x 216 in. Courtesy of the artist and Sonje Museum, Kyungju, Korea.

Do you want to unpack for us the role your identity plays in terms of your body of work?

I think that it’s related to the difference between adaptation and assimilation, or intuition and instinct. I will set up conditions or parameters for encounter and then go along with them and react to the set-up. The body’s reaction to these new conditions might be seen as analogous to how our perceptions of identity are continually in flux. In “Salt Transfer Cycle” I wanted this Asian protagonist to go from east to west by going west rather than going towards the east. So I started in Chinatown, which I thought was appropriate, and had dumped 2,000 pounds of MSG into my studio with cranes and such. Then I did a performance of swimming through the MSG.

So there was an audience?

No, it was just the camera people. It wasn’t so important to me that it was open to an audience at the time. I knew that it was going to be documented, and in a way the fact of doing it was enough—the one take was part of the whole point of it. It wasn’t an endurance test, but it had to do with completion of a task, I guess. And then seeing what it looked like.

I understand—that much MSG, does it do something to your body when you’re swimming in it?

It’s always debated, but I’m pretty allergic to it and I grew up with it in the household all the time. After the performance, there was a cloud of broken MSG crystal floating in the air, and I had fallen down, I think, that day and gotten a cut, so I was getting it in my blood. Yeah, it definitely made me feel a bit dizzy…

At which point did you realize that you had to address the fact that you’re Asian in your work?

That was something I was very conscious of from the beginning. That’s why I thought of putting the image of myself back into the work, even though I had done other live performances for closed circuit. I had done installations that were based upon the residue of a lot of activity, but I still wouldn’t feature my own image which I felt was adversely affecting the perceptions of the work itself.

Because of the label: Korean-American?

Sure, yeah. And that knowledge of it, even if it wasn’t said.

But I feel like you can’t escape it, right? Your work is always going to come with a label.

Sure, but you can avoid it to some extent. And at the time I was taking advantage of some of it: Pan-Asian stereotypes. I grew up as a relatively isolated member of that “group” in the Midwest, as a kid with very few role models in popular culture, so I grew up kind of obsessed with rejecting all those things. When I did my first show in ’92 and work before that, through grad school, occasionally it would touch or play upon things I was exposed to, which had a lot to do with some of the naming, or shallowness of naming in the Pan-Asian sphere. So when I did this piece, it was very much about giving people what they were asking for. It was putting this primal Asian character, naked and everything, right out in front of you. And I don’t think I really thought about it too much at the time, but my hair happened to be very long, so there was a bit of a slippage between identities, whether it was indigenous—people thought I was Native American, or whatever it might have been. That kind of slippage interested me too. It’s grossly generalizing based upon its physical nature.

Michael Joo, “Smokescreen”, 1996. Video Projector, Vinyl. Dimensions Variable. Courtesy of the artist.

This concept of slippage is interesting. The body as an image – the crossovers between gender, race and identity. Aspects of the body itself perceived as labels for identification.

I was dealing a lot with the actions and ramifications of making sculpture, and thinking about what happened along the route from conceptualizing an artwork, initiating the process of its development, and what happens before it becomes something, or in a way, what’s in between concept and process, and what happens before it gets to residue. In the case of this particular work, it was a question of what happened with calories and energy expended during its making. What happened to what was invisible. Salt was used as a stand-in for energy, or sweat, and MSG was the artifice. In the three parts of the video I swam through a ton of MSG in my studio in Chinatown, ran across the Salt Flats in Utah, accumulating salt on my body as the residue of the activity. Finally, I waited on a hillside in South Korea as a human salt lick for local elk. I thought I would enact a transformation of artifice (or concept) in the studio, and follow that idea’s gradual transformation into salt that was licked off of my body by animals; into something that was so real, it got into the blood stream of the elk and fabric of reality.

Was this the point when the natural world came into your work?

No, it had come up often before, but this was the most direct instance. I still thought of the natural world as a 24 hour factory. A foil for thoughts on production and manufacturing; producing ready-made artifacts like antlers continually.

So is the elk a ready-made or is the cycle that the elk fits into a ready-made?

A bit of both perhaps. I think that the cycle that the elk undergoes from mating impulse to rutting to the dropping of the antlers might be seen as a kind of manufacturing cycle.

So it’s almost like Warhol using the soup can; the can representing the final product of an industrial process. When objects are assembled and placed, each one contains its own cycle. Does that make sense? When you pull in the elk’s antlers, that’s the icon, the image as a representative of the cycle. And this piece is just wow too, spanning from Utah to Korea.

The middle point of that, after swimming through 2,000 pounds of MSG, was to get to a place where it was very real – where the MSG, the artificial flavor enhancer became this bed of pure geologically produced salt. So I went to the salt beds of Utah and found by coordinates the place where they actually raced the speed record cars from the 70s and I ran along that path, parodying evolution. Something that was really linear, but linear in the way that it was futilely cyclical, like land-speed record runs, expending all this energy to set a record that would only stand to be broken. Those perversions of cyclical and linear elements are something I think of as a play between Western and Eastern motifs.

Michael Joo. “Mongoloid-Version B-29 (Miss Megook Painting #1)” 1993-2003. Aluminum aircraft fuselage, stainless steel, enamel paint, urethane varnish. 88 x 72 x 24 in. Photograph by Tom Powel Imaging. Courtesy of the artist.

I want to talk now about “Mongoloid Version B-29 (Miss Megook Paintings #1 and #2)”, because it kind of connects your bodies.

It’s still a continuation of that group of work. I was putting myself, my image, back in the work, and trying to address different perceptions about reality. “Salt Transfer Cycle”, I think, was concerned with present tense. We’re going to take this salt off my body and put it in their blood stream, you know, and you can shit and piss it out, or sweat it out. It was a metaphor for reality. In “Miss Megook…”, I wanted to work with something that dealt with the past to distort reality. I started collecting parts from airplanes that flew over Korea or China during the Korean War; that shared the same air-space, and in effect the same social, political, and historical space as my parents.

So I went to the desert in Arizona and started combing some of the airplane graveyards and hooked up with this old Air Force fellow who let me cut out old parts of old cargo planes that flew over Korea in the war. I was interested in this particular plane called “Miss-Megook”, which would literally mean “miss me gook”, aimed at the North Koreans or Chinese, you know, Miss This Plane. So it was kind of a derogatory challenge, and then in a way, I liked the confusion that “megook” in Korean means “American.” So that kind of play, is a fairly conscious Duchampian gesture. I was also interested that an image was used to give the plane identity.

Right. “Salt Transfer Cycle” was specific, but it still kind of passes the parallel, the human cycle. Then “Miss Megook” is going further into a specific “event,” it happened and it’s extremely political. Really like, addressing a political aspect of history and playing with that, as you did in “Smokescreen.” Would you like to talk about that?

Many of my works are concerned with the idea of fragmentation and reunification, or a kind of reassembly or reconstruction. “Smokescreen” is a video work that I shot at the immigration and naturalization building at the World Trade Towers in the early 90s. I shot the flag from behind, from the backside and then re-projected it through smoke. I thought that the artificial smoke that made an extrusion of the video projection light would be a way of bringing together a two-dimensional icon and three-dimensional reality and space.

So you were writing the names with a laser in between that space?

That’s right, I was writing the names of all the countries I could remember that the US was involved with commercially or militarily. It was basically every country I could remember, and I was writing it with a laser pen and watching out simultaneously for guards.

So now let’s talk about some earlier work like “Headless (Mfg. Portrait)”, your use of Buddha and your relationship with Buddhism. I think it comes up in a few pieces, your use of the Buddha sculpture.

I grew up in a household with both Christian and traditional Korean Buddhist practices. The Buddhist was eventually pushed out and only remained as books and texts. Buddhism occupied a space for me that was kind of esoteric and intellectual. I found out more about it in texts because it wasn’t so much in practice. My mother was very Christian. At the time we used to have a lot of Korean practices, ancestor worship and such things, as well as some practices that were a direct offshoot of Buddhism. But the temples in the house all disappeared over time. Shadows of some kind of past. It seemed real. It seemed about space. Christianity pushed Buddhism out, so it seemed to be something that was lost.

You’re talking about the “Bodi Obfuscatus”, so the camera abstraction, you’re saying it’s lost, is that action to reinvestigate the loss?

The Buddhist iconography for me in any of the sculptures that I use, they’re always headless. They’re always more like the leftovers of Angkor Wat, and I always see them as sculpture that’s been desecrated. So there’s something that signals incompletion, as well as a sort of misleading stereotypical profile of an identity. Because it looks like the Buddha, but it’s just a body, no face and there’s no head. The position of the body of Buddha often means something, but really the visage, as far as that it’s sculpture, means almost everything. So it’s always missing to me and replaced with something technological, American, or western, rather.

Right, “Headless.”

Yeah, I mean “Headless (Mfg. Portrait)”, they were 64 casts of Nerf-foam bodies sculpted to look like those of a seated Buddha figure and hand-colored with actual terracotta mixed with pigment. Then I inserted neodymium magnets into the bodies and heads, keeping these toy heads from 100 years of American manufacturing suspended over the bodies. So those things are an identity that was designed in America, made in Asia and brought back to America over a hundred years of time. I think of the collection of heads as a self-portrait of manufacturing.

It’s interesting that the heads of the original Buddha usually come here.

Yeah, as art artifacts bearing testimony to colonial times. The bodies are left behind.

Lets talk about what the sculpture “God II” relates to—does it relate to “Circannual Rhythm (Pibloktok)”, the piece you did at the List Visual Arts Center at MIT?

“God II” is a sculpture cast in resin that was clothed in a mix of my father’s clothes and used clothing given to me by Inupiaq hunter friends. The sculpture is placed on a super-refrigerated base that transforms the viewers’ breath, perspiration etc., into a mass of ice that slowly envelops and obliterates the figure. I guess it could relate to “Circannual Rhythm” if you see it as a work that questions the center… That piece is a three channel video, with each channel made up of three individual frames, all projected in a fifty foot long composite of images. So set of nine, so three sets of three, and each of these veins, to me, deal with different perceptions of time and space. The first part, which is the central part, depicts a journey north along the Dalton Highway in Alaska, following the Trans-Alaska pipeline. I liked the idea of walking this roadway up to the north where the land is actually disappearing and which becomes a sort of seasonal landscape of ice. I thought of it as strangely parallel to transformation over time of organic matter to fossil fuel, and was further interested in the small amount of human energy or calories you’d expend walking against the flow of some millions of years’ worth of fossil fuel. So transformation is another theme common to both works. In other parts of “Circannual Rhythm”, I outfitted a taxidermied caribou sculpture with infrared cameras in its body cavity, placed it in the Denali Park wilderness and videotaped from the sculpture’s perspective from a quarter mile away for ten days. A final aspect of the work involved an Inupiaq whale hunter having a seizure on the frozen edge of the Arctic Ocean.

I guess I’m interested in this piece because it seems like a progression or related to the “Salt Transfer” piece, and also I was trying to relate it to “God II.” Was it in the same show?

Yeah, it was. But I had made “God II” previously, actually. I had made “God II” before that. But at the time I had been exploring Alaska.

Your work has been called “hermetic philosophy”? That’s an interesting phrase. I don’t know if I totally agree with that. Is it too much for one to assume it’s “hermetic”?

If by hermetic you mean, possessed of its own internal logic, then it might apply. But not in an obtuse or inaccessible way. Understanding is a bit overrated because sometimes it means encapsulating and being categorized. I don’t know if that’s always the right thing. The hermetic practice implies kind of hieroglyphic signs, and fragments, parts of a campfire to try to put together the story of how those bones got there. More recently I have trained fifty live surveillance cameras on the visage of a 3rd Century BC statue of the Buddha, dispersing the fragmented images throughout hundreds of mirrors and monitors surrounding the space. I have also been casting molds of sculptures as the final work, and destroying the originals or trying to replicate the gestural paintings made by protestors onto police riot shields during clashes over economic policies. They deal with the idea of simultaneity. Nothing is hidden in these works. They are the shadows of their former selves and selves to be. The evidence and logic is contained within them and right in front of you.