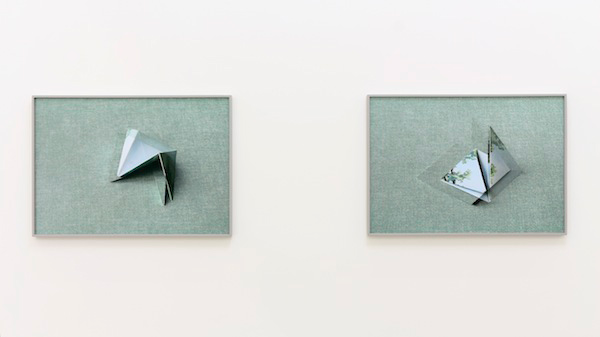

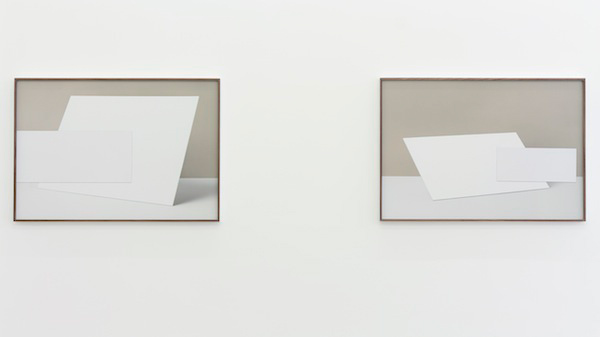

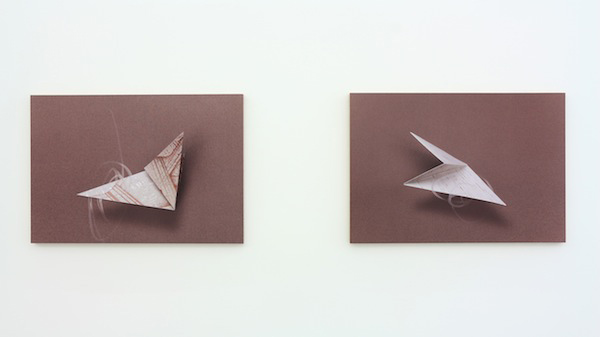

Miriam Böhm takes a photograph of something banal, prints it, alters it (re-sizes it, folds it, tilts it, or turns it into an accordion book), and re-photographs the altered photograph against the initial photograph’s background. The work is clean, but it isn’t beautiful. Three to five photographs of the altered photograph are lined up in a row. There is so little going on, coupled with the repetition of an image that wasn’t that great the first time, that experiencing Böhm’s work is a meditation. As with all art, what the viewer meditates on is mostly a reflection of the viewer. Art critics on Miriam Böhm tend to flail, grasping for something tangible and easy to summarize.

Many critics evaluate Böhm’s work by referencing optics in an attempt to seem intelligent or to be exclusionary with vocabulary, but wind up demonstrating their own ignorance by misusing it. Lea Feinstein described Böhm’s and Shannon Ebner’s work as “about photographic vision and the monocular eye, the illusion of three-dimensional space subverted by the reality of a flat surface” in Art Practical. Böhm’s work appears very three-dimensional, but yeah, it’s two-dimensional—that’s not subversion, that’s a photograph. A “monocular” single eye, or camera’s lens, reduces depth-of-field, and opens up field of vision; however, since Böhm resizes the photograph object within the photograph, there’s no illusion that we are seeing a wider perspective of the same picture. Artforum’s Brendan Fey also deserves the pretention prize for “parallax in potentia.” Oy.

The disorienting nature of the work is used as an excuse for an equally shaky interpretation. In ArtSlant, Andy Ritchie wrote:

the doubling of imagery can be a bit confusing to the senses. (…) When the source photo’s bubble wrap aligns with the bubble wrap beneath it, I sense an unreliable reflection, like deja vu in a way.

This is a lazy mimicry of profundity, in a way. Nothing about Böhm’s work is bewildering. Shadows give everything away.

On Böhm’s conceptually similar work “Inventory” from 2010, both The San Francsico Chronicle’s Kenneth Baker and Brendan Fey incorrectly label her photographs of photographs as recursive. Recursion is an infinite phenomenon, like the endless repeating reflections of two mirrors held up to each other; recursive art has the same incomprehensible monumentality as fractals, man. Christine Wong Yap got it right in Art Practical, writing:

she utilizes only one level of re-photography here, thereby avoiding the temptation of nihilistic recursion and trite statements about endless reproducibility.

Böhm’s work is, in fact, self-referential; think “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.”

The most literate analysis of Böhm’s photographs is Franklin Melendez’s comparison to “Barthes’s critique of a world become object” in Artforum in 2010. Roland Barthes’s critique focuses on Dutch still lifes, and argues that foodstuffs are stripped of their functionality and reduced to their adjectives, e.g. the twinkle of juice in a cut lemon rather than the scurvy-fighting nutrition of a lemon. In the same way, Böhm’s initial photograph is stripped of its function as an art photograph in the traditional sense when it’s folded into a plane or turned into an accordion book. Further, the second photograph of the altered photograph object deprives the object of its function; the tangibility of the accordion book would have use and a greater presence as an art object than a photograph of it. Luckily, the final photograph of Böhm’s on the wall and Bathes’s rhetoric are brought full circle with his idea of structuralism:

Creation or reflection are not, here, and original “impression” of the world, but a veritable fabrication of a world which resembles the first one, not in order to copy it but to render it intelligible (1128).

By thinking about Böhm’s object within the context of a photograph, we are giving it meaning and making sense of it. Böhm’s works are a way toward a thought process, and the banality of their subject matter is like training wheels. They are a mental exercise to get you ready for works where the paradigm is the same, but more difficult to see.

“Miriam Böhm: Before in Front” is on view at Ratio 3 through December 14.

-Kendall George

Citations:

Baker, Kenneth. “Odd spatial shifts carefully placed in Ratio 3 space.” San Francisco Chronicle Apr 2010.

Barthes, Roland. “The Structuralist Activity.” Critical Theory Since Plato. Ed. Hazard Adams. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971. 1128-1130.

Feinstein, Lea. “They Knew What They Wanted.” Art Practical Jul 2010.

Melendez, Franklin. “Critics’ Pick: Miriam Böhm.” Artforum.com April 2010.

Ritchie, Andy. “Böhm at Ratio 3.” ArtSlant Mar 2010. Wong Yap, Christine. “Inventory.” Art Practical Mar 2010. Image Citations: All images are from “Miriam Böhm: Before in Front” via Ratio 3.