In a remarkable photograph from 1926 in the Security Pacific National Bank Collection at the Los Angeles Public Library, two workers dressed in dapper hats, slacks, and shirts, plant fully grown, slender Mexican fan palm trees into the soil along Wilshire Boulevard, between Western and Wilton. In the background are the perfectly regimented rows of palms they have already installed to line the street—as they do today, but perhaps not for much longer.

The bizarre botanical history of palm trees in Los Angeles is hardly a secret. In 1931, an ornamental planting frenzy introduced more than 25,000 imported tropical trees to the Southern California landscape. Most of these alien species became ubiquitous almost overnight, and are now the region’s most cliché icons, instantly associated with good times, good weather, and vacation vibes. A palm tree is the ultimate in easy aesthetics: pretty, finely shaped, and exotic.

Palms are, however, essentially useless. They promise a lot, but they offer very little, providing barely any shade from the pounding sun; they suck up copious amounts of water, which is a contentious ecological issue in a desert city. They’re also dying. Many of the palm varieties planted 100 years ago are now nearing the end of their natural lives. They were brought to the US to be decorative, but now they are a reminder of displacement and of the brutality of man over nature, a kind of ecological imperialism. Walking around Echo Park Lake, they look eerie, waiting, so it seems, to act out some Day of the Triffids-style revenge as you contemplate a ride on a paddleboat.

The irresistible illusionism of LA’s palms has kept them in fashion for decades, with appearances in Art Deco posters, David Hockney’s paintings, to Kahlil Joseph’s film, Double Conscience (2014), presented at MOCA last year. For many artists who have lived, worked or passed through the city, the palm cliché inevitably finds a way into their work, ensuring preservation in the public subconscious. The more something is repeated, the safer it is to copy it. Ed Ruscha’s iconoclastic 1971 photo book, A Few Palm Trees, uprooted the urban palm once again, planting them into the contemporary art’s intellectual and visual discourse. His deadpan document of the varieties of trees found across the Los Angeles landscape, is, as Joan Didion put it in her catalog essay for his show at the 2005 Venice Biennale, a distillation: “the thing compressed to its most pure essence.” The palm cliché is Los Angeles. In an email, I asked John Baldessari why he likes to dapple his work with palms. He wrote back, “I like palm trees because they’re unlike any other tree in their shape, and also because they’re a cliché for Southern California.”

As a synecdoche of West Coast culture—and a part of near-universal pop culture aesthetics—palms are naturally great material for artists. Yet they’re not appealing only for their omnipresence. Their dark past and equally glum future—where the artificial and the natural have been horribly reversed—given them a subtle political resonance. The cliché is turned back on its audience.

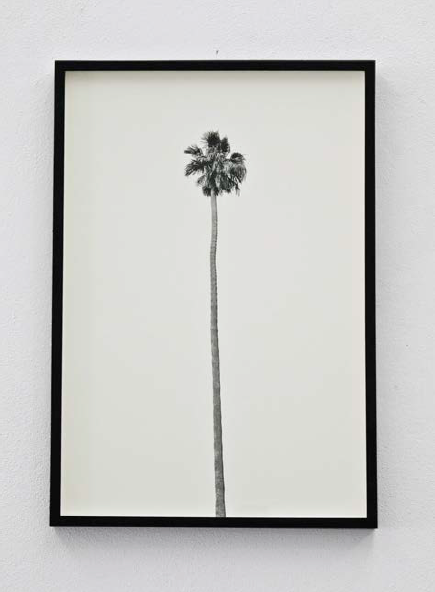

Adrien Missika, A Dying Generation #4, 2011. Black and white laser prints, 49 x 39 centimeters. Edition of 5. Photograph by Martin Argyroglo. Courtesy of BUGADA & CARGNEL.

Ruscha’s artist’s book inspired Paris-born, Berlin-based Adrien Missika’s photo series A Dying Generation (2011), presented in front of a giant wallpaper backdrop of waves at his solo exhibition at Galleria SpazioA in Pistoia, Italy. Like Ruscha, Missika is interested in the language of advertising and its exchange with the modern imagination: Do we really dream up the tropical vacation idyll all by ourselves? Ruscha’s typology is rooted in the region while Missika—who looks at LA from a distance and was initially draw to the city by its seductive image—considers the nature of representation of foreign things once they are removed from their context. For his series Missika, in direct reference to Ruscha, revisited and rephotographed the Los Angeles palms that Ruscha captured 40 years before. Hanging solemnly, the artist’s photographs show the trees in the 21st century, inviting a laconic reflection on environmental change and the fragility of nature in the Anthropocene and the equivocal nature of images in capturing that reality when seen abroad. In 1971 and in 2011, both Ruscha and Missika give us pretty pictures that slowly turn into an ugly truth.

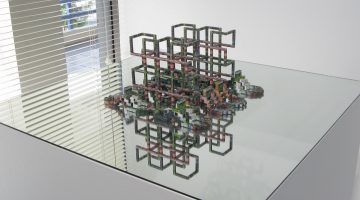

Installation view, Laura Poitras, A Way to Leak, Lick, Leek, 2016. Vinyl tiles, resin, various electronic items, paper sheeting, iPads, iPhones, tablet screens, foliage, metal, plastic, wood, cables, polyester seats. Courtesy of the artist and MOT International. Commission: Fahrenheit by FLAX. (Background) Lick in the Past, 2016. Video, Duration 8:23 min. Courtesy of the artist and MOT International. Commission: Fahrenheit by FLAX. © Jeff McLane.

For artists who spend time in Los Angeles—the need to confront the palm tree cliché is inevitable, a way to question the way the city has been constructed and the way it continues to be perceived. Following her residency in Los Angeles last year, Laure Prouvost’s installation at Fahrenheit—titled A Way To Leak, Lick, Leek—drew out the darker roots of the flora and fauna of Los Angeles. In a 360-degree installation, inspired by the surroundings and substances she encountered while in the city, the plants created a post-apocalyptic atmosphere, sinister and plastic, overbearing rather than protective. Their leaves glowed thickly in a twilight ambience. Similarly, LA resident Evan Holloway presents the charm of the palm as both alluring and fake. His Plants and Lamps (2015), a sculptural installation made out of steel, cardboard, resin, fiberglass and sandbags presented at David Kordansky in the spring of 2016, carried connotations of a distorted Californian ideology—the paradox of neoliberalism that begs for biodiversity and sustainability, yet feeds from an artificial, polluting light. The mystifying, terrifying, and pathetic tale of the palm tree, as shown to us in the art of Los Angeles, is the guts of what Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron refer to in their 1995 essay, The Californian Ideology, as the “West Coast’s Extropian cult”—the hell-bent desire to improve human life with technology. As the last palms of Los Angeles sway in the desert air, I can’t help but wonder what will happen when they’re gone forever, and exist only in images? In another hundred years, if the palms disappear from the landscape, the cliché will shift to the status of idol. Or perhaps, this immigrant community of trees will resist their fate somehow, reemerge, and like so much life that has passed through LA, survive.