William Corwin and Neil Greenberg

The Great Richmond: Find Yourself a Borough

Staten Island Arts Culture Lounge, St. George Ferry Terminal Station

Silver cities rise

the morning lights

the streets that meet them

and sirens call them on with a song

—Carly Simon “Let the River Run”

Melanie Griffith’s teased hair quivering in the morning breeze on the Staten Island Ferry, staring longingly ahead into glittering Manhattan, commuting into the city with professional and social aspirations. We all know the odds are against her (Her clothes! Her accent!) but nevertheless we’re rooting for her to succeed—that’s Lady Liberty looking on, and Carly Simon, backed by church choir, singing “let the river run, the new Jerusalem.” This scene from Mike Nichols “Working Girl” (1988) came to me riding the Staten Island ferry back from seeing William Corwin and Neil Greenberg’s “The Great Richmond” in the Staten Island ferry terminal. Both are dreams of futurity, fantasies of dealing with the struggles of the city in an American way.

Neil Greenberg, Urban “What If” Map, 2013. Crayon, ink, and colored pencil on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Staten Island Arts

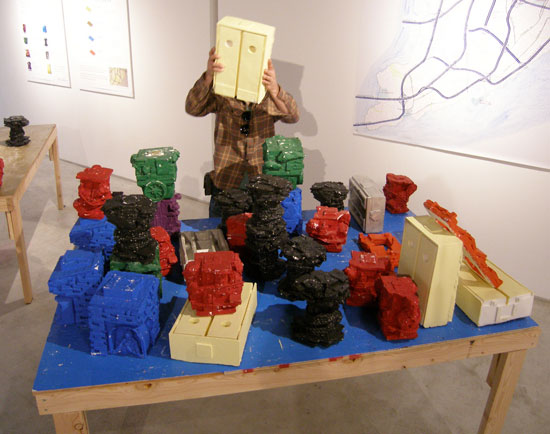

“The Great Richmond” is sculpture as provisional game. In the Ferry Terminal’s “culture lounge” there are four platforms representing possible directions for Staten Island’s development (urban, suburban, agricultural, “secession from NYC”) and eight types of hand-sized sculptures by Corwin stacked on shelves, symbolizing specific attributes (infrastructure, housing, government institutions, etc.) which can be arranged on the platforms. Neil Greenberg, the experimental urban cartographer, made four “What If” map sketches for the walls, illustrating possible forms that these futures might take, but ultimately in “The Great Richmond” the island’s fate is turned over to the thousands of commuters that pass through the terminal every day. Visitors are encouraged to stop and move the pieces as they see fit, constructing their ideal vision of Staten Island,with each subsequent arrangement shifting or obliterating the previous one. Corwin carefully documented this process, generating hundreds of photographs of people playing and making temporary sculptures of their dream society.

Installation view, “The Great Richmond,” at Staten Island Arts, 2014. Courtesy of Staten Island Arts

Like most of Corwin’s recent work “The Great Richmond” uses the structures of games to engage serious subjects. In this case it looks at the most pressing question for New York City: how do we create and maintain a space for rich diversity and social democracy in the face of overpowering private interest? As David Harvey argued in “The Right to the City”: “the question of what kind of city we want cannot be divorced from the question of what kind of people we want to be, what kinds of social relations we seek, what relations to nature we cherish, what style of daily life we desire, what kinds of technologies we deem appropriate, what aesthetic values we hold. The right to the city is, therefore, far more than a right of individual access to the resources that the city embodies: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city more after our heart’s desire.” In this light, the playful proposition of “The Great Richmond” takes on greater meaning, opening a pocket for the collect envisioning of our shared future. For, as Harvey says, “the freedom to make and remake ourselves and our cities is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet neglected of our human rights,” and here Corwin and Greenberg present us with such a potential, using art to remind us of our radical ability to reconstruct life.