For more than four decades, Lita Albuquerque has been on a diversified yet aesthetically and conceptually cohesive mission, making installations, ephemeral environments, performances involving the artist alone or hundreds of participants, large-scale public commissions, paintings, drawings, and sculptures. Born in Santa Monica, she was raised in Tunisia and Paris before returning to California. In the 1970s she was associated with the Light and Space movement, creating poetically fleeting pigment pieces in the desert; the beginnings of a lifelong quest to map personal identity in the face of the universe’s infinitude; a humanistic investigation of what it means to be one person, alone, yet simultaneously connected to the unfathomable vastness of both outer and inner space. This grappling with the enormity of boundless expanses and eternal time is not mere rhetoric. In Albuquerque’s case it is the basis for a heartfelt sifting through of the multiple meanings of what that entails, and she remains an embodiment of unflagging curiosity, vibrant and vital, and very much active in the now. The latest manifestation of that is a dream turned creative reality, a vision of a future astronaut crash-landed in Mali six millennia before Christ. 20/20: Accelerando, her new multimedia space and time travel epic, will make its debut at USC’s Fisher Museum of Art, opening January 24, 2016.

This might seem like an odd start, but this quote of yours reflects on an extremely important aspect of what you do. My sense from an art historical perspective is that people shy away from talking about this, but it appears to be essential to everything you do, so why not begin there. To paraphrase, you’ve said, “Consciousness is the prize of life.” What does that mean exactly?

I love that you are starting the interview with that question. I couldn’t be happier because it really is an integral part of my thinking and what I mean by that is that, in the end what we have left, what we take away from life, is just that: our consciousness, the development of our consciousness. And I believe it goes beyond life—it is the gift of life, that’s why I said that. I believe that.

Beyond the corporeal.

Yes, beyond that and, therefore, the most important thing to do is to develop that consciousness. And I don’t know why I have such a belief in it, but I do.

Does this consciousness, after the lifetime of one individual, still exist in some form?

Yes, and it did exist before. I’m on the core faculty of the Fine Art Graduate Program at Art Center College of Design, and I took my students to Mexico and to the Yucatán. Do you know what Cenotes are? They’re caves that are 30 feet under the surface of the earth and full of water. The Mayans have built ladders down to the water and I took my students there and had this experience: I was in the water lying down, I’m focusing on the time and location and I’m looking up the root of an aloe tree 30 feet up—the roots are hanging down from the surface of the earth—and then thirty feet up through this hole to the sky, and I couldn’t help but think in terms of seeing the horn of the Yucatán as if I was looking from outer space, and here I was way underneath the earth, and all of a sudden it was like I really got the connection between—well, what I saw was a robe of thousands of galaxies and way, way, way down there was the Milky Way Galaxy, so it was this kind of relationship of where we are in the grand scheme of things.

So light that eight billion years ago left a star and arrived at Earth and through photosynthesis gave life. Is it at that level of literalness? That this energy of light in particular, which I know you talk about a lot, came here—is it the essence of energy through light that comes through to you or me?

Yes, it’s very much about physics, it’s that. But also what I got at that moment was the relationship of all these galaxies to the soul, and the correlation between time and space, between the cosmos and the individual. The immensity of the cape was like the immensity of all the lives and that my lying in the water under the earth was just one of my lives, almost as if the millions of galaxies were also the millions of lives?

A transcendence of time. Obviously those are traditional religious concepts, but this has a more scientific aspect to it, a synthesis of the religious and secular, if I understand correctly. And matter doesn’t get created or go away, it’s always transformed, and energy is perpetually there in some shape or form. I’m not a physicist, but that’s the way I understand it. I wanted to ask you that to start because there are other possible interpretations.

Your consciousness is really what you take away from life.

I think of it being an awareness of the other, and an awareness of what is around you, not just taking it for granted. Which I think is often what people do, which is kind of understandable. It’s easier.

Yes, the other way is really hard and there are no maps. That’s a heavy-duty start to the interview! But just to continue that—there’s no such thing as completion, it is about understanding and perceiving the body in space and time.

You also said that you want to “develop a visual language that brings the realities of time and space to a human scale.” Does there need to be a translation of the realities of time and space? Is that what your work is about on some level?

Exactly, that’s what I’m interested in—the visualization. What I’m trying to do as an artist is on the one hand, create an emotional response with material and color which brings us to the body (or perception), and on another to utilize a more scientific way and visualize some of these concepts through geometry and these concepts always start out as an image.

Like the stranded astronaut from 20/20: Accelerando, which we’re going to talk more about.

Yes, like the astronaut waking up and just seeing herself, and then she realizes—actually another influence is Egypt. I don’t know if you’ve been to Cairo?

No, I haven’t.

The Museum of Cairo is one of my favorite museums. I don’t know if you’ve heard about it. It’s, well, a mess.

Like the state museums in China: they’re dusty, drab, dirty, and neglected, and that’s why I like them.

Me too! So in this one huge room in Cairo are all these sarcophagi and they’re all looking up. I’ve always been fascinated with that upward gaze and what that implies. I also heard that schooling initiates had to go inside the sarcophagus with the lid on top. So I imagine my astronaut like that.

What’s compelling is that your work doesn’t have a stereotypical science fiction look at all, though there is a science fiction element. A very familiar trope is the traveler in a suspended animation pod that opens up like a sarcophagus and they wake up and groggily emerge after a journey of hundreds of years. What you are describing has a correlation to things that have been visualized in movies and novels, but it doesn’t look like that. It’s more fundamental.

From space to Earth, related, I know you were quite young, but you spent time in Tunisia, and then you ended up doing work in the desert, and again, the desert is a big part of the science fiction imagination, as in Star Wars and Dune. When you started doing work in the Mojave was there a conscious connection to the Tunisia of your childhood?

It was all historical. It’s interesting, you would think there would be that connection, but really it was seeing earth art, and friends of mine who actually had gone—John Gordon and John Sturgeon, video artists we were in school together—and they went to the desert and did their work. And I was thinking, “Whoa, what if I just put color out there in this minimalist space!” It was the minimalist space that fascinated me.

The blank geological canvas. Were you aware of Michael Heizer at that time?

Yes, of course. At that point I had very little outside influence besides my circle of friends at UCLA. Even with Yves Klein, my friend the artist Susan Kaiser Vogel started using blue which may or not have been influenced by him, and I started using blue inspired by her, but I did not know of him. So it was this indirect lineage.

Let’s talk about Malibu Line, a blue line leaving the beach. The water is leaving the water, the basin of the ocean, up on to the land, and then presumably to the sky. That’s the ocean, and the desert is the opposite of the ocean.

Well, Tunisia has both. So does California.

Malibu Line, 1978. Pigment, 41 feet x 14 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Kohn Gallery.

Those transitory works like Blue Rock, where the pigment on the rock gets blown away, there’s entropy, and that’s part of the universe winding down. And this is back to consciousness—is that piece a small version of that overall degeneration?

Yes.

You’re making artwork and you want people to see it and experience it, but it’s temporary and disappears.

Totally.

You made Rock and Pigment Installation in the Mojave the same year. Is that a landscape painting? They remind me of Yves Tanguy, particularly his The Furniture of Time. Do you think of those installations as painting landscapes?

I certainly wasn’t thinking of Yves Tanguy or surrealists, but when I applied the pigment to the rocks it was a move from painting to sculpture, it was about time, too, about a gesture. It was the idea of, in a way, a painterly gesture, but also the gesture of a body’s relationship to either the horizon line or the sky. Malibu Line had to do with the horizon line; Rock and Pigment Installation was the first installation where I did a reflection of the stars. Man and the Mountain #2 was the relationship to the horizon line, how the body is situated almost out of the Earth’s plane, but still on the Earth. A gesture in relationship to the horizon, the sun, or the moon. It’s very elemental.

People were painting on canvases and, to make a gross generalization, many of them simultaneously in different parts of the world decided to leave the canvas behind. There was something in the air, it seems.

Completely in the air.

What was your personal motive? Was it conceptually really thought out, or was it more an inchoate feeling?

I was really intrigued with moving away from the wall and using the land as a two-dimensional drawing surface. The first one was what I just said in terms of the relationship of the body to the landscape. I was taking dance and I lived on this property, an artist’s colony called Coffee House Positano, which had 132 acres of land overlooking the ocean. I really grew up and developed as an artist there. I really became aware of location and space.

To get into painting, your desert pieces started off as what most would consider abstraction. They’re abstract paintings in the landscape.

I don’t think of them as abstract paintings in the landscape, I think of bringing color to the landscape and making marks that would be gestures in relation to the space around me.

That’s intriguing. Prior to written language, symbols—going back 40,000 years or however long—might have developed from trying to mimic the body’s correspondence to the Earth. Maybe this is sort of obvious, but in Man and the Mountain I, also from 1978, you look at it and there’s the shadow and to me it looks precisely like primitive drawings.

Isn’t that amazing!

Was that intentional?

No! My friends went up there, and I was like, “Oh my God, you look exactly like the petroglyphs.”

So you noticed that, too. And I was talking about science fiction, but those figures, which are found in petroglyphs all around the world, have a frightening scarecrow-like quality that reminds me of seeing the first Planet of the Apes as a kid.

Yes, it’s odd.

Man and the Mountain #1, 1978. Death Valley, California. Courtesy of the artist and Kohn Gallery.

There’s something foreboding about them. They’re simplified, menacing stickmen.

And it comes from shadows.

Primitive man or woman saw another man and his shadow. Is that the beginning of representation? Wanting to express the idea of the other person or the animal, but not having a tool to do so, and then realizing that shadows could give them a way?

It could be. It would be interesting to find out if it’s been written about. And if shadow is the beginning of representation, that’s really interesting, because of what shadows symbolically represent, and the relation to the sun.

There’s an ironic feature of ephemeral artwork and land art, and specifically with your Sol Star installation at the Great Pyramids of Giza, which are in a way the ultimate in land art.

And permanent.

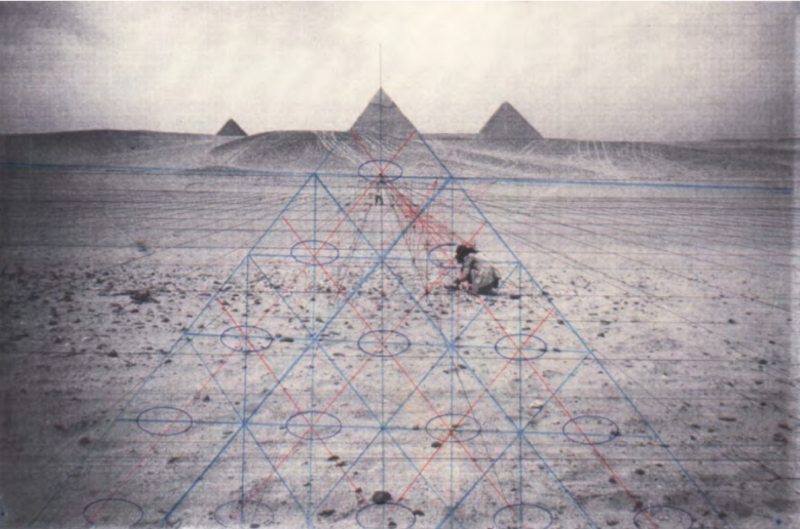

Sol Star (Triangular Grid), 2013 (from preliminary study for the Sixth Cairo International Biennale, 1996). Pigment print on silver paper, 16.5 x 13 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Kohn Gallery.

You talk about entropy and impermanence and though the pyramids won’t last forever, they’ve survived longer than almost anything else humans have done. Were you conscious of that at the time? That you were doing something deliberately that wouldn’t last next to massive constructions that have?

It was not conscious at the time, I’ll be honest, but it’s pretty great, the two.

Circles, squares, and triangles. Underlying geometries.

Yes, I was interested in underlying geometries and how the pyramids would fit exactly in an imaginary hexagonal pattern in the sky. I almost got kicked out of the country because originally the piece was going to be this hexagonal pattern in front of the pyramids, and they thought it was a Star of David. But what is fascinating is if you do a hexagonal pattern—which Pythagoras made his students meditate on every day—if you do that over the pyramids they fit into the hexagon.

Again, associated with painting or just modernism overall, the geometric 1920s international avant-garde use of basic shapes—was that at all on your mind? Malevich and the rest?

I love Malevich; I just think he’s an absolute champion of art history, but also that entire period. I went to the opening of the new Whitney and on the eighth floor they have some early Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley and Stuart Davis, and it’s something I really love, but really it had more to do with ancient man using these very primal shapes. The cross, the spiral, the circle, and the square.

Which are repeated in all cultures.

Everywhere. I was also studying sacred geometry quite a bit at that time.

With the original Spine of the Earth in 1980 the participants were in a circle, and in the 2012 iteration at Baldwin Hill in Los Angeles, it was an unfurling of the circle, an unspooling. They walked straight down the path on Baldwin Hill as if the circle turned into a line.

Yes. From a circle to a line. It was like that. And people actually told me they could see it from the freeway! I had called it Spine of the Earth when it was flat, and then the 2012 version was literally like a spine.

Spine of the Earth 2012, 2015 (from Spine of the Earth 2012, performance for the Getty Museum Pacific Standard Time Performance and Public Art Festival, Baldwin Hills Overlook, Los Angeles, 2012). Inkjet print, 50 x 60 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Kohn Gallery. Photograph by Marissa Roth.

So you grew up—

I grew up Catholic.

Oh, I wasn’t going to that ask, but did you grow up, after Tunisia and France, in California?

Yes, I arrived in 1957. We actually arrived in New York December 31, 1956. We then went to Scottsdale. My mother only had one contact in the United States. She was a playwright, and her contact was a designer for Frank Lloyd Wright, and we met Frank Lloyd Wright.

You met the leader of the cult.

We ended up in Scottsdale for six months, and then we came here. I actually lived in Malibu right over there. I lived on the beach.

Were you into the whole nature scene, hiking and being outside?

I was really solitary. I thought I was going to be a poet, and I loved the beach.

How was the beach?

It was great. I loved it and I loved bicycling.

So you were active, out and about. California in the 1950s might have been as close as you could get to a certain kind of suntanned paradise.

It was golden, it was Gidget. I lived next to James Arness.

Really?

I hardly spoke English at that time, I was just learning. So it was like the United States and TV!

That immersion in wilderness, maybe “earthy” is not the best word to use, but what you do certainly reflects an essential physical connection with the Earth.

I go swimming every day.

You’re not an armchair nature person. And you’ve done art in Antarctica and the North Pole, places of extreme climates at the opposite ends of the Earth.

When I did Stellar Axis: 90 Degrees North, I lay down on my stomach and lapped the water—the sweetest water I’ve tasted in my entire life. Just amazing. If I fell in there and died, it would be okay.

There are worse ways to go. You mentioned Yves Klein and your feeling of connection to him. Klein is well known but there remains a mystique even if he’s become entrenched in the canon. There’s the sensational, naked-women-as-paintbrushes, the Anthropometry series, but also varied and arcane territory in the fairly short span of his life. One of those “the light that burns twice as bright burns half as long” situations, to use a cliché from Bladerunner. Obviously, people must ask you about the blue you use, a very deep hue, since it’s so similar to International Klein Blue.

Sidi Bou Said and Carthage in Tunisia are very much like Greece, all whitewashed with blue. The Mediterranean, the landscape, the white and the blue, and Klein was from Nice, across the Mediterranean from there. The relationship to the sky is what I was interested in more than anything, to unite the Earth and the sky. And then later on I read about Yves Klein and Arman and how in their twenties Yves claimed the sky, and Arman claimed plenitude. And I wondered, “What am I claiming?” And I made a claim—claiming the relationship between the Earth and the sky.

Bringing them together. So then there’s not just the color, obviously.

In his case, it comes from not only the Mediterranean, but also Klein’s involvement in Rosicrucianism, Judo, the body, the physicality of it, but more than anything he was able to visualize the Earth from space before we even had that capability, which is extraordinary. A lot of his imagery comes from Rosicrucianism. I didn’t know much about Rosecrucianism so I decided I’d better learn about it to understand him, and interestingly the internal exercises I have created over the years bring me to that same place, though it’s not necessarily scholarly.

Rosicrucianism is Gnostic, cryptic knowledge, but your work is less scholarly, as you said.

It’s less from somewhere external; from something learned and less from specific spiritual or religious practices; it’s something experienced.

With Klein the connection is about internality?

Yes, it is about interiority, it comes from within, and I have trained myself through various practices I have developed over the years to sense myself in the now in the now of the space time continuum. It may sound . . . but in actually, in terms of physics, it is what is happening in a very objective sense. We just never really think outside of our 3D reality, but we exist in a much vaster and complex system, I am interested in visualizing this, so the viewer can actually get there just by experiencing the work, a tall order I know, I think it is achieved subliminally.

I’ve done all these practices like automatic writing and going running on the beach while doing these intense breathing exercises. Maybe it’s because I was put in a convent for school when I was three—so I was very solitary and I had to go internally, and I also had the whole Catholic pageantry and symbolism. I think all of these more scholarly or more esoteric groups are about—initially it came internally and then started to get passed down from the originator, becoming externalized. And the Rosicrucians talk about blue; they talk a lot about color.

Your pigment paintings are predominantly blue and red. Is it a coincidence they look like those Hubble Telescope pictures? They have that milky galaxy in space look that you get in these photos, or the Aurora Borealis, I’m sure people say.

Or the wind.

Yes, and to extrapolate, solar wind. But those paintings, they have the tie-in with the cosmos and the macro and the micro.

Those paintings come from the wind, but I do think a lot in terms of supernova explosions and the beginning of everything. I’m not surprised that we have violence in us because we come from violence.

The Big Bang was really violent.

Yes! We’re completely from violence.

Everyone is in favor of stopping humans from being violent but on a cosmic level violence is a basis of life.

The charcoal drawings from 2005 also look alien, though in that “ancient mysteries” sense, like the Cerne Abbas Giant in Dorset holding a big club and with a really big penis.

Those came from my energetic meditations: You start out running, and inhale from the sun to your heart, and exhale from your heart to the sun ten times. As you do this at different times of the day. It’s like living geometry. The next one arms extended, head thrown back, you do 33 breath of fire into the sky. Then you exhale, and when you have completely exhaled the breath, you inhale and spiral the breath clockwise around all the chakras, then you go back and you do it the other way around, and repeat it three times.

That’s what’s in those drawings?

They’re describing that. Another connection that I’m interested in—we are in space.

Yes, we are flying around through space.

We are in outer space, and that’s what I love. We really never—we don’t think that way, right? It’s so interesting to me, how we perceive. If we could see it, we’re just one of those little dots out there that isn’t seen because planets—we’re not a star, so we’re not visible. The only way we’re visible actually is if we get in front of a star, just this little blip, right?

Yes, a negligible speck in the immeasurable sweep. So coming up at the Salar de Uyuni salt flats in Bolivia, for 20/20: Accelerando, the crash-landing in Mali six thousand years ago, that’s what you are working on now?

What I am working on now is 20/20: Accelerando which will be exhibited at the Fisher Museum at USC in LA. I am hoping to shoot part of the project at the Salt Flats. My going to Bolivia was originally going to be this 24-hour performance with hundreds of people, but it’s 12,000 feet high so possibly not too feasible. I just received a Santa Monica Artist Fellowship grant for my writing and performance work, and now I am thinking of going there to shoot part of 20/20: Accelerando. So it certainly won’t be the whole performance, or it may even be Part II, but it will give me images that I need for this project and I’ll be able to understand what I need to do there for the extended piece.

You said you had the origins quite a while ago.

Yes, I wrote the original narrative in 2003, and I did not use it in my work until 2014 with Particle Horizon exhibited at the Laguna Museum of Art. But first I want to show you something called An Elongated Now, which I did at the Laguna Art Museum in 2014 which served as a prologue to Particle Horizon. The original idea was for hundreds of people dressed in white to go on the arc of the beach in Laguna and point to the sunrise, all watch the sunrise, so they would be all pointing, and then at noon, and then at sunset, and then come back. But it was impossible.

An Elongated Now, 2014. Documentation of performance for the Laguna Museum of Art, Art and Nature Festival. 300 performers dressed in white parallel the arc of Main Beach, Laguna over 3⁄4 of a mile. Laguna Beach, California. Photograph by Eric Minh Swenson. Courtesy of the artist and Kohn Gallery.

Logistically?

Logistically it just wasn’t realistic, so I thought, “Okay, I’ll just have them come at sunset.” They were to stay there and stand there from sunset until nighttime and then go into the museum to be part of Particle Horizon. It was quite a feat.

20/20: Accelerando is a development of that work which is about a 25th-century female astronaut who crash-landed in what is now Mali in the year 6,000 BC, and her mission is to show the inhabitants of planet Earth about their relationship to the stars. But when she enters earth’s atmosphere she forgets everything and forgets her mission. So she does all these overlays of maps and tries to figure out what is what. The performance begins with the naming of the stars sung in the space as well as on a video that will be projected. In Stellar Axis: Antarctica, there were 99 stars that were aligned to 99 blue spheres on the ice of the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica, so I wanted to have singers do that which would also serve to contextualize her character and her mission. I’m collaborating with video artist and composer Robbie C. Williamson and there’s an alien language with English subtitles sung by Cassandra Bickman. it’s how the stars are being spoken, which is kind of wonderful. This is going to be a performance with musicians, singers, and dancers. This part I’m showing to you, with the audio, so you can hear the sound of the stars.