The circumstances were perhaps special on the early afternoon of May 31st, 2013 in central Istanbul, when disproportionate use of violence by police forces, in response to an environmental protest, escalated into one of the major popular uprisings in the history of Turkey, a country not particularly skilled at handling dissent peacefully. Yes, the circumstances were exceptional, as the reality of violence brought Turks from all walks of life together in an episodic moment of participatory democracy, albeit only in the form of contestation and not of agreement, which turned the country upside down. The complex set of relations dictating contemporary urban life means that a protest movement for the environment today is also about architecture, about housing, about inequality, and ultimately about the public and political domain.

Journalistic comparisons to Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring or May 1968, did very little to clarify what this moment of transition was or could have been. How do you address a moment of transition when you are profoundly immersed in it? This question haunted Turkish artist Didem Pekün, observing the uprising from London as a distant spectator, and then arriving back in Istanbul to take part in the protests that lasted for months and that still echo profoundly in the political consciousness of the present moment in Turkey, marred by increasing political uncertainty and the possibility of next door’s war in Syria penetrating Turkey’s porous border. Where do the borders of reality meet the horizon of what is visible to us?

These moments of convolution that all those involved in the protests remember to a degree now seem further than they really are, as if they were part of a political cosmology erasing all previous histories yet so deeply embedded in them. The protests spread quickly nationwide, and in the unexpected solidarity that is born as a consequence of losing the objective world, very few people in central Istanbul slept that night and witnessed the hundreds of protesters marching from one side of the Bosphorus Bridge to the other at 4 AM, as we broke into tears from both shock and excitement. And that was only the beginning.

Didem Pekün had begun her ongoing project Of Dice and Men, already in 2011 during an anti-austerity demonstration in London, two years before the events of Gezi Park. Upon returning to Istanbul, the artist’s lens was met with raw footage from iconic moments of the Gezi Park protests, juxtaposed by a pre-existing visual monologue, staged between London and Istanbul, in which the artist reflects on the possibility of the everyday, existing alongside so many different forms of violence. Referring to a cultural unconscious, the momentum of Gezi is not an interruption by the final episode of a cycle of accumulation: global tension and uncertainty. The work is executed, albeit poetically, in a radical social realism operating a suitable model to subvert the possibility to dismiss this historical accumulation merely as apocalyptic fiction.

Didem Pekün, Of Dice and Men, 2011. Video Loop, 29 minutes. Courtesy of SALT and the artist. Photography by Baris Dogrusoz.

To live in the moment or to document the moment? A strange seamlessness foams up in between the truly cinematic and the more intimate descriptions of the everyday: a tram in London, or a window view from Istanbul. As cosmic background waves, the grandeur of the temporal ruptures; the intoxication of the future breaks through the sewn patches of the here-and-now. Passing through a number of different adopted positions, Pekün doubles and triples into persons and voices, into moments and eras, into histories and telltales. But Of Dice and Men is not a filmic essay about a protest movement somewhere, which sounds very ubiquitous today and not particularly incisive. The anxious loop between the everyday and the sublime and the artist’s question of whether we are able to move back and forth between them, and how, is not something specific to Gezi or Istanbul or Turkey but related to a profound moment of change and global transition of which Gezi is only a late symptom.

It is then not surprising that Of Dice and Men is the work at the core of A Century of Centuries, the exhibition curated by November Paynter that took place this year at SALT Beyoğlu, which was marked by the hundred-year commemoration of the Armenian Genocide in Istanbul, to this date not recognized by the government of Turkey. As in 2013, when the Gezi Park protesters battled the police and the clouds of tear gas, so it was in 2015 when demonstrators marching in recognition of the centennial of the genocide were followed closely by Turkish nationalists separated only by a very thin police barrier as they passed the Siniossoglou Apartment building that today houses SALT Beyoğlu. Paynter was primarily interested in works imbued with the memory of temporal transformations that continue to shape our present moment here and elsewhere.

But “transformation” is not strong enough a noun to denote the temporal gaps being addressed here. A transformation is merely a conversion from one symbol or function into a different one of similar value, whereas a transition implies a change in morphology, a crossover. A moment of transition is one in which the validity of certain concepts or symbols that guide us through the structure of reality begins to fail, thus we are expected to build new concepts based on knowledge of the past and wild guessing about the future. The transition is not a temporal unit but a leaped second; an adjustment that corrects time.

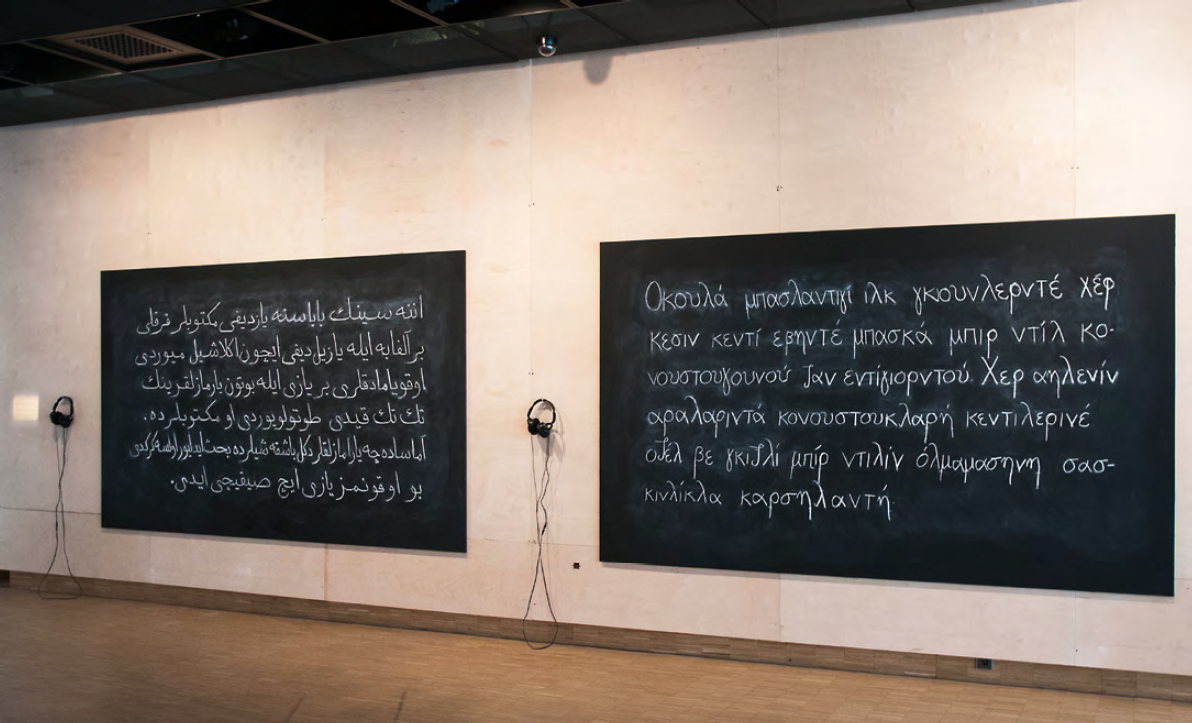

The installation as if nothing has ever been said before us (2007–2015) by Dilek Winchester, another local artist living on the islands of Istanbul—a place of exile and imprisonment in Byzantine times and later a place for minorities—takes on the polyglossic nature of Turkey in the early-20th century, rescuing cultural forms that have been buried in oblivion after the language and alphabet reforms in Turkey led to a rather violent and merciless process of homogenization and unification, which begot many of Turkey’s distinctively authoritarian and intolerant traits. Winchester’s investigation looks into Karamanlidika—Turkish written in the Greek alphabet—and Armeno-Turkish—Turkish written in the Armenian alphabet—and reveals buried chapters of Turkish literary history, where the first novels in modern Turkish were written by minority authors, using their own alphabets, but never registered in the official literary history.

Dilek Winchester, As If Nothing Has Ever Been Said Before Us, 2007-2015. Courtesy of SALT and the artist. Photograph by Mustafa Hazneci.

In as if nothing has ever been said before us, Winchester explores the ideology of identity in relation to language, the title of which is based in the writer Oğuz Atay’s 1971 novel Tutunamayanlar (The Disconnected): “We are knocking on your doors with an emotion and arrogance unparalleled in world history and without fear of seeming like those who are conceited and behave as if nothing has ever been said before them.” The phonetic transcription is in Turkish but the alphabets include Armenian, Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic, all used extensively by the Ottoman population until the language reforms. As varieties of historical time are embedded in language, Winchester addresses the political consequences of linguistic policies and their long-term effects on the physical location of pasts: do they still shed light on us?

On the same floor, Hera Büyüktaşcıyan, Winchester’s neighbor on the same island, constructs a dialogue across time that complements the former’s investigation on Karamanlidika and Armeno-Turkish with a poetic utterance traveling far across eras. Profoundly engaged with the history of Greeks and Armenians in Istanbul, it is not a place of diaspora or exile for Büyüktaşcıyan but the epicenter of cultural and linguistic history of centuries. The artist travels in time and place between Byzantium, Constantinople, Venice, the Prince Islands, and Istanbul, and further back to a Babylonian cuneiform text of the epic of Atrahasis, also known as the tale of Noah’s Ark. Destroy your house, build up a boat, save life (2014–2015), titled after a quote from the Babylonian text, builds an imaginary boat and a boat of imaginaries that make reference to the fragility yet durability of memory through gestures and symbols. Not unlike Winchester, Büyüktaşcıyan digs out an archaeology of invisible symbols, erstwhile erased from Istanbul’s long history of exiles and persecutions.

Hera Büyüktaşçıyan, Destroy your house, build up a boat, save life!, 2014-2015 and Docks, 2014. Courtesy of SALT and the artist. Photograph by Mustafa Hazneci.

Rolled carpets act as an oblique metaphor for the suspended home, the condition of rootlessness: the shift of cultural forms, transition from one religion to another and ultimately between eras, the exile of the Christian minorities of Istanbul and nowadays the status of Syrian refugees who wait in legal limbo in Turkey and attempt to reach fortress Europe on boats with little else than the clothes they are wearing, in the same way that the once impoverished Europeans reached for Constantinople, many centuries ago. Grounding the metaphor and connecting it to the site, Büyüktaşcıyan unveiled as a part of the work a ceiling painting at the Siniossoglou Apartment, where the Greek minority once lived. Docks (2014), presented as a structure with moving planks, completes the idea of transition through mental and physical spaces: is there no safe ground? Moving between different histories of the city, the artist draws a map of permanently unstable lines.

Returning from the islands and the obscurities of the previous century to present-day Istanbul, Yasemin Özcan tackles article 301 of the Turkish penal code, which took effect 10 years ago and makes it a criminal offense to insult the state or government institutions. In threehundredone (2008), Özcan reacts to the prosecution by the state and subsequent assassination of Armenian-Turkish journalist Hrant Dink—an icon for freedom of speech—in 2007. The artist produced a necklace bearing only the numbers 301, working with Armenian craftsmen in one of Istanbul’s traditional craftsmanship centers, protesting the article almost silently, considering broader aspects of gender, justice, and freedom in Turkey. Other artists in the past have also been taken to court for infringing upon this article, most notably Hale Tenger’s case in the 1990s when she was prosecuted for insulting the Turkish flag in one of her signature installations.

Specially commissioned for A Century of Centuries, and lively articulating the preoccupations of the exhibition, is Trailer (2015), a lecture-performance by Erinç Aslanboğa, Natalie Heller, and Bahar Temiz. It offered a real-time look into how memories are organized and therefore how elements of the past can be gathered and re-organized: Where exactly are we when we remember? Is this a personal space or one we share with others? Navigating the no-longer and not-yet-of-consciousness, as they relate to broader frameworks that include historical and social knowledge, how do we merge different temporalities into a consistent seamless whole? While the question is not answered by the performance, the artists involved turn to movement from theoretical knowledge and attempt to create something such as movement or dance scores based on memories, which are also part of an extended web of political events and interruptions in the flow of consciousness: revolution, upheaval, dictatorship, freedom.

November Paynter’s eye and focus in selecting the artists for the exhibition expanded into a larger question about the nature of our historical consciousness, far beyond Turkey, to include Russian collective Chto Delat? with their performance-installation The Excluded. In a Moment of Danger (2014) addresses forms of political organization of subjects under different forms of oppression, subtle and otherwise, and Kapwani Kiwanga’s installation . . . rumors Maji was a lie (2014) based on accounts of the 1905–1907 uprising in the African continent against the Germans led by a spiritual medium, resonate strongly within the exhibition, but it is difficult not to be overpowered by the loud volume of the conversation between Turkish artists, especially bearing in mind the erratic nature of contemporary art in the country, where it is very difficult to find meeting points between the practices of artists living in the same city; something consistent with the transformative moments that Paynter sought after.

Other works in the exhibition include Judith Raum’s eser (2014–2015), documenting German colonialism in Anatolia; Jumana Manna and Sille Storihle’s The Goodness Regime (2013), a film about the foundations of ideology and national self-image in Norway; Maha Maamoun’s videos about Egypt’s visual history; and Shilpa Gupta’s Untitled (2013–2014), dealing with geographical tensions between India and Pakistan. As a generalization, all the works in the exhibition investigate the becoming of our present world not in terms of causes, effects, and consequences, but under the light of how untold or obscured histories—be they visual, cultural, political, linguistic—can affect profound transformations in how we relate to immediacy or the past or not, and whether that will cause us to be derailed from the present into a frenzied state of suspended judgment where we are unable to move between past and future, between fiction and fact, between history and myth.

Almost hidden in plain view, lying quite anonymously in the middle of the exhibition, was the work that encapsulated the exhibition best. Dilek Winchester’s hermetic Negative Epiphany (2015) is a series of black prints made by overexposing paper, developed in traditional printing techniques and presented alongside vintage cameras from 1900–1915. The prints are not metaphorical; they stand blackened in lieu of photographs that have been shot somewhere, but that cannot be shown in the exhibition. Does this refer to images that we forgot or to objects that disappeared? To things that are not present or that have not been imagined? The work does not reveal much—a vault with indecipherable documents. The transmission of knowledge does not occur as an uninterrupted consciousness, therefore it is imperative to excavate, and to let objects speak for themselves, rather than to accommodate them.

It seems as if the central question of A Century of Centuries is not one of personal or even collective narratives, but what happens in politics and in artistic production when different moments in time pose themselves simultaneously as starting points of historical knowledge and as political futures. Our concept of history, as it stands today, is far removed from the way in which our ancestors looked at their narrated lives, and belongs to the 18th-century Enlightenment, in which the determinations for human experience were laid out rationally, removed from experience itself. It is a politico-philosophical concept. Historical time, should there be one, is bound up with our social and political circumstances and no longer anchored in a metaphysical hierarchy. To locate this time with precision is not merely a function of knowledge, or even of orientation, but of discovering how to move between different eras without being under the illusion that one or the other determines the whole.

What are the markers between one era and the other? Say, if you want to discuss the dividing line between the 19th century and the 20th and the 21st, what key events or places would come to mind? At the turning point between reality and belief, this long century placed between the imperialism of Bismarck’s Germany in the 1860s and that of corporate interests in the Middle East and elsewhere in 2015, is one and the same century punctuated by some of the most defining humanitarian crises of the modern era: the Armenian genocide in 1915 inaugurating the era of crimes against humanity and the indiscriminate slaughter of Syrians and Iraqis in 2015, which effectively ended that era together with international law and the international treaties enshrined to protect refugees all over the world from the horrors of genocide.

Not surprisingly, we are living in a very similar momentum, part and parcel of the same unfinished century: at the gates of a promising new world, propelled by economic and scientific growth, significant constitutional reforms and liberalization of the legal apparatus, reduction of poverty, and a fragile world peace. All of this paired with unspeakable humanitarian crises, the threat of an impending war, and the destruction of the middle classes. In order to “finish” this century, to move into the new one and pick up on the sublime that Didem Pekün was offering us in her work, it is necessary to think up forms of the future in which the current system of social and political organization will not be a “necessary evil” or an “inescapable circumstance” for those wanting to live in a democracy. It takes more than good judgment to walk into the future. It also takes imagination. A Century of Centuries imagines in reverse: it looks at the past as if it had shed light on the future.