Manifesta 11

What People Do for Money: Some Joint Ventures

Zürich, Switzerland

June 11 – September 18, 2016

On view in Zürich throughout multiple venues until September 18, 2016 is Manifesta 11. Titled What People Do for Money: Some Joint Ventures and curated by artist Christian Jankowski, Manifesta 11 examines the dynamics of labor and the effect of “work” on daily life and art production. As part of what is possibly an apophenia-induced and coincidental constellation of labor-focused European exhibitions this summer (notably the 9th Berlin Biennale’s The Future in Drag and the Hamburger Bahnhof’s Capital: Debt – Territory – Utopia), What People Do for Money diverges significantly, both in its sheer breadth of topics and by Jankowski’s curatorial style.

Jankowski’s touch is evident throughout the exhibition. As he has done in his previous works—such as Casting Jesus (2011), which investigates the performative aspects of work by pitting professional actors vying for the role of Christ against a jury comprising of a priest, a journalist, an art critic—Jankowski employs the artists’ submissions as vignettes, which explore the various lives and practices of workers throughout time and space. Jankowski and co-curator Francesca Gavin employ a rather straightforward arrangement of this theme: exhibition rooms and venues are divided up into different professions, modes of work, leisure, and time frames. The result, is both superficially didactic and charming in its ironic naiveté, maintaining the classical division of labor, all the while piercing it through the artists’ intervention.

Installation view, Portraits of Professions. Manifesta11. Image courtesy of Manifesta11

At almost every juncture of the Löwenbräukunst and Helmhaus venues, the curators attempt to break from the model of the white cube, lifting works away from the periphery of the walls and affixing them to a network of metal frames. While this physical similarity to a worksite’s scaffold may seem too literal for some, the horizontal and vertical members help to emphasize the relationship between pieces, creating moments for interesting interactions. As a permeable surface, the frames’ transparency enables other pieces to peer through the web of metal and mounted images. As older works from “The Historical Exhibition: Sites Under Construction” are often attached to these metal trusses and newer commissions set either on walls or installed within the gallery, these structures create an added layer of dimensionality, both in space and time, further breaking the rigidity of the white cube.

Matyáš Chochola, Löwenbräukunst, 2016. Photo courtesy of Manifesta11/Wolfgang Traeger.

The results of this strategy are seen throughout. In the room titled “Portraits of Professions,” a collection of historical photographs of city workers taken by Yto Barrada, Tjorg Douglas Beer, Werner Büttner, and Olga Chernysheva (just to name a few) is presented as a grid of images, linked together through their subject matter and similar formalistic approach of re-presenting of the worker as an individual. One can guess through their clothing and through the depicted setting what occupations they may have had. Beyond this web of the framed photographs is Czech artist Matyáš Chochola’s sculptural intervention Ultra Violet Ritual (2016). Consisting of trophies, chains, video monitors, punching bags, and boxing ephemera, it documents the artist’s collaboration with multiple Muay Thai boxing world champion Azem Maksutaj through offering the artifacts of their shared experience. Whereas the aforementioned collected photographs offer a level of intimacy with their uncomplicated look into the lives of workers through portraiture, Chochola’s installation removes the individual, leaving the viewer to piece together aspects of the boxer’s discipline and practice through the traces it leaves.

Vuk Ćosić, ASCII Taxi Driver Year, 1998. ASCII Video Dimensions: 1’29” Courtesy of the artist

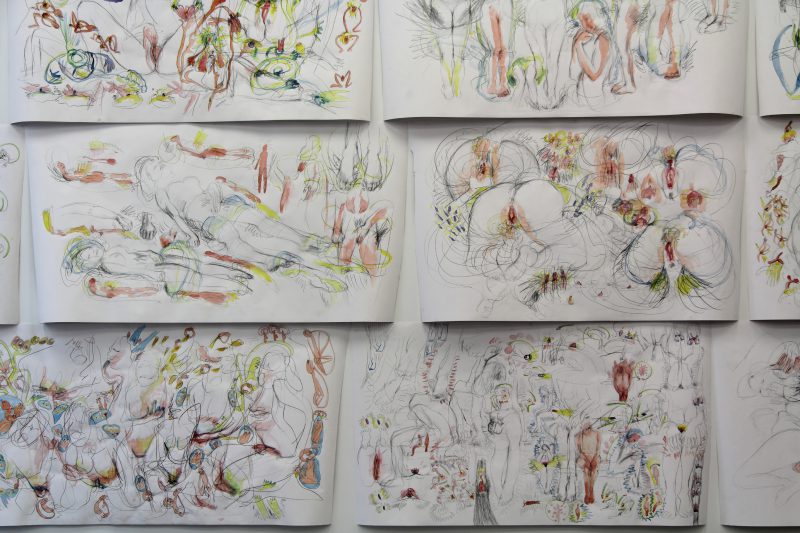

In the room “Art as a Second Profession,” Jankowski employs a series of works in which the artist came to art through a variety of different means. Examples of this abound, such as the net.art pioneer Vuk Ćosić, whose 1998 work Taxi Driver is the 1976 film reproduced in ASCII code, resulting in a low resolution image consisting of various electric-green numbers, letters, and characters scrolling over a black computer monitor. Also in this room is Andrea Éva Györi’s new work, the series Expedition in VibrationHighWay (2016). In this, she depicts a series of women in the throes of orgasmic passion, using a fast, cursory style, expressing her subjects in wild flashes of pink, orange, yellow, and exposed pencil lines. Györi captures the humor as well as the dreams and exultations of the women she depicts, translating the lead up and moment of climax, as well as the ease or difficulty her subjects experience to reach this moment. The images, worked-out over a series of monumental sheets of paper, were the result of observations she conducted made in collaboration with a sex educator and specialist psychologist in sexology. In both works, the artist is framed as a specialist, either as a clinical observer translating complex psychological phenomena or as a programmer of systems converting data into recognizable images.

Andrea Éva Győri, Expedition in VibrationHighWay, Löwenbräukunst. Photo courtesy of Manifesta11/Wolfgang Traeger

In Pegasus Dance: Choreography for Police Water Cannon Trucks (2007) featured in the room “Professions Performing in Art”, Spanish artist Fernando Sánchez Castillo films two police water cannon trucks playing out a dance set to a Strauss waltz. Through their series of circular motions, the two vehicles act out a sort of melodrama, replete with a sense of romance, longing, and triumph. While the vehicles are themselves lifeless, the juxtaposition of this against their synchronous movement, the copious arcs and splashes of their water cannons, and the pomp of the instrumental accompaniment communicate a sense of passion and joy. As is seen throughout What People Do for Money, Pegasus Dance exemplifies the possibility of amusement through labor. While this may just be a fantasy produced by an artist, the work then offers insight into the role of art in producing society’s understanding of what work is. The historical depiction of the happy worker has been, for centuries, an image produced and reproduced by artists. Often done to romanticize labor or mock it, the result of such images was the same: the viewer became removed from the reality of work. Castillo plays with this notion, creating a piece that is both absurd and beautiful.

Fernando Sánchez Castillo, Pegasus Dance: Choreography for Riot Trucks, 2008. Image courtesy of Manifesta 11

What People Do for Money offers a kaleidoscopic view of the topic of labor, demonstrated through the constant shifting in tone from overtly political to surreal and absurd. Employing curatorial strategies that emphasize the permeable nature between time and space, work and art, Jankowski creates what Jacques Rancière calls the “aesthetic experience,” with the gallery spaces establishing a “multiplicity of folds and gaps in the fabric of common experience that changes the cartography of the perceptible.”[1] Within this context, the dual forces of art and work are united through the common thread of performance, highlighting tensions and contradictions in western culture that have historically kept the two apart. Perhaps it is that Jankowski, a German artist being tasked to curate a European biennial in Zürich, understands the performative aspect of this all too well. The notion of an “outsider” taking on another role, the fluid, sometimes awkward, transmutation of work practice to art practice and visa versa, seems to be at the core of the exhibition. As artists collaborate with a variety of professions, each momentarily adopts a new persona, something is shared, and their talents and expertise seem to inform and color their performance. While not attempting to offer a utopic vision, from the nature of the spaces created and emphasis on the unity of work and art as performance, there comes a sense of shared fate.

[1] Rancière, Jacques. “Aesthetic Separation, Aesthetic Community: Scenes from the Aesthetic Regime of Art.” Art & Research: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods Volume 2. No. 1 (Summer 2008): 11.