Interviewed by Paul Karlstrom

What follows is an edited-for-publication version of the verbatim transcript of an interview with San Francisco Art Institute President Charles Desmarais. Conducted by Paul Karlstrom on May 30, 2012, the interview took place in the subject’s office at SFAI.

“…Frankly, my understanding of the institution is that it is much more than a school. The way the school and its artists have engaged with the community—whether in a political or cultural sense—is the soul of this place, and the center of my own interest. You called it a marriage; it’s a perfect marriage in that sense. The Art Institute and I are soul mates.”

Charles, we’re sitting in your office at SFAI to record an interview for San Francisco Arts Quarterly, which will be another introduction of you to the Bay Area art community. So why don’t you introduce yourself to get us started.

Okay. I’m Charles Desmarais. I am the president of the San Francisco Art Institute, as of this past August.

Not quite a year—but plenty of time to find about this place and your new job. The topic is really you and the Art Institute: how you came together, what you found when you arrived, what you could build on, what needed to be changed. In sum, what did you bring to SFAI? I see from your résumé that you’ve worked at quite a few institutions.

Yes, I’ve had a number of different positions, virtually all in museums, virtually all as director of museums. So this is certainly a big change for me. It’s my first academic administration job. I tend not to like the word “administration,” or even the term “arts management.” It might sound a little pretentious, but I prefer “leadership.”

So this is a kind of leap. But I guess the big question to dispatch here is how your background—especially in museums—prepared you for running an art school?

Well, I think in certain ways I wasn’t prepared. And that was one of the things that intrigued me when I was asked to apply for the job, because I was looking for a new adventure. But I think managing complex institutions is a skill that is transferrable. And working with eighteen curators, as I did at the Brooklyn Museum, is analogous to working with faculty. But more important is that I think art schools, in general, have lost much of their connection to the community and to the art world. Let’s remember that the Art Institute is not unique in this. But SFAI was founded in 1871 as the San Francisco Art Association and it had a broad mandate. It was very much about promoting artists, promoting their work in the community, promoting art in this region.

And to create a market for art.

Well, certainly to create a market was a big part of it, but I think there was a broader intellectual purpose: to engage people in this discussion that the artists were excited by. And how do you broaden that discussion? Certainly they had to support themselves. [But] the institution was founded with this broad community purpose that included education. Over time it lost that larger community focus to some degree. And when I was asked to apply for this job, all of us who were finalists were asked to address the board and the rest of the Art Institute faculty and student body, and I talked about that function of the Institute and how I thought that we should work to recover that original purpose and focus.

So before you even came here, when you were going through this process that eventually led to your selection as president, you were thinking about the identity of the Art Institute within the community—the basis for its unique presence—and that maybe it got off track in terms of what its history represented… and promised.

Yeah, at least that was my perception from a distance. To go back to your questions— why I made the move from museums and what I brought from museums to this job. Having been a museum director for several decades, I think I have a pretty good understanding of how museums connect with their audiences, and I have a pretty good understanding now—or at least some hints—about how we might be able to better connect the Art Institute to the museum world and to the art world.

So, that was the case I made, and I think it’s part of my mandate. I had no specific interest in working at a college. I was very happy and I had a very good job in one of the major art museums in this country. But this place has played such an important role in art—this is where so many artistic movements were introduced, where so many great artists worked. So, as soon as I learned that it was the San Francisco Art Institute calling, I got really excited. To think that I might be able to have some of that [aura] rub off on me. Or even better, to have the opportunity to create a new history, to continue that history in some way.

You seem to be professing prenuptial love.

That’s right.

And as I hear you, you’re thinking of the Art Institute as embodying a role and objectives that go well beyond application of skills on the outside, in the workplace. This has to do with the training of artists, to the extent that you can actually train them—which is another question.

A very good question. … Frankly, my understanding of the institution is that it is much more than a school. The way the school and its artists have engaged with the community—whether in a political or cultural sense—is the soul of this place, and the center of my own interest. You called it a marriage; it’s a perfect marriage in that sense. The Art Institute and I are soul mates.

In that case, how are your own ideas about art reflected in or connected to SFAI?

The Art Institute is—for lack of a better description and I haven’t come up with one yet— a Fine Art school. We don’t teach design, architecture, or fashion. That’s where a lot of the gravy is, frankly, in the art school business. But we’re far from a business in that sense. So that sort of very deliberate choice of an institution to focus on the core of art appealed to me very much. …

I was born in New York and by first grade we had moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut. I grew up the oldest of seven kids in a blue-collar family where there was no discussion of art. My dad was a sheet-metal worker with a third grade education. In a certain way, I feel as though art saved my life. … When I was exposed to art totally by chance [Time magazine led me to MoMA at age fifteen] I realized that my life could be about something beyond just working. And to be able to share that with young people—to get to the educational mission of this place—is an extremely wonderful honor. So you combine that sort of match of backgrounds and focus on the essence of the interpretation or investigation of culture through visual art, that’s one strong connection for me to this place.

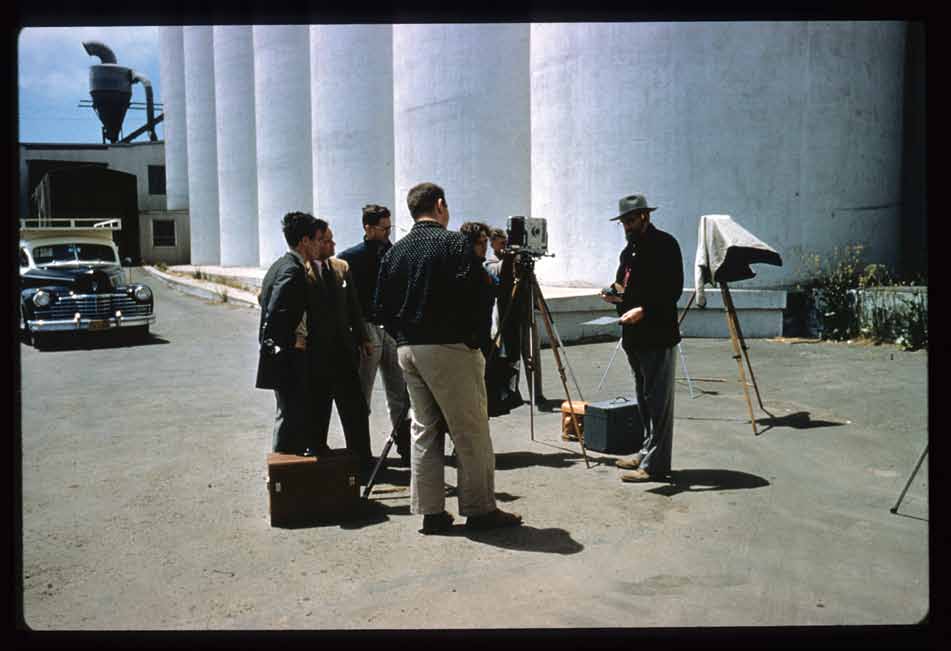

A field trip in a photo class c. late 1950s with faculty member Pirkle Jones, visitor, Ansel Adams and students. Courtesy of SFAI.

How and where did higher education become part of your story?

First I went into the Catholic seminary for two years—this was at high school age—and that’s where I think I became somewhat politicized because that was an era when progressive Catholic priests were strong thinkers about the church’s role in society. So we did a lot of thinking and talking about that kind of thing. … In fact, I don’t think I could take a job that I didn’t feel I had some special mission to perform. I have always seen myself as a student of art. Most of my jobs have been as a curator and museum director, but unlike many curators, I’ve never felt as though my job is to tell people what to like or tell people what’s important as much as it is to share with people what I’m learning and share the excitement of that.

But you’re openly attached to this school, you had a relationship, some sort of an affair with SFAI before you actually came here. I get the sense that you have a belief in a social imperative—a social commitment, a kind of idealism as opposed to simple pragmatism.

I think you’re right that I am an idealist and that I think this institution and art institutions in general have a social responsibility. It’s not, by the way, about art that is “socially conscious.”

Okay, this is one of the big questions for me, how you feel about that responsibility. You’ve suggested this concern is something that you communicated to the board when you were speaking with them.

I certainly didn’t get much into the detail of my personal life. But this idea that my life was saved— because the only part of my life that really matters is the way that I’ve learned to look at the world—to look at society through the arts, starting with visual art. I suppose for some people it might be religion, but for me it’s a non-sectarian way to interpret the world and make sense of it. I find it endlessly engaging.

So you might think of art as a calling. That’s one way to describe an artist engaged in art as idea as opposed to a commercial artist. Something that has a higher meaning—I’m making it sound slightly like religion but …

Yeah, okay. And quite honestly, I see the relationship to religion in my own life. But you could easily see the relationship, say, to science. I mean, the way that the most passionate of scientists have an entire world open to them because they have a lens through which to see the world and to interpret it and to try and puzzle out how it works. And I think that artists do that in their sphere and scientists do it in theirs. The commercial artist rarely crosses the line into what you and I might think of as the real thing—”Fine Art” as some people call it. Trying to define art is extremely difficult, and you do it at great risk. But the artist who is analyzing herself, analyzing her culture, using these tools to first try to understand and then try to share that understanding with an audience, I think that’s the part that I’m interested in. The part that is made to entertain us or to decorate our world or decorate ourselves, or whatever, is also of interest, but that’s not the part we’re talking about and that’s not the part that the Art Institute is about. We’re creating thinkers.

I see much better now why you’re so happy to have arrived here, because it brings together most aspects of most of your career along with your personal values.

No question about it. My entire career has led me here.

That’s fair enough. But what have you found that may be different from what you expected and maybe not in a positive way? There must be some disappointments.

I think that’s a totally fair question. And particularly because so many people love this institution, people have paid attention to its successes but also some of the difficulties that it’s had. And it has certainly had difficulties in recent years. I knew there had been financial difficulties. There had been great stresses between the faculty and the last administration, between the board and the last administration. What I didn’t realize was that there would still be open wounds that still needed to be healed. I don’t shy away from that responsibility, but the problem is that there are some who still are so pained that it makes them suspicious, untrusting of my motives.

Are you thinking about faculty or board— or both?

I’m thinking particularly about faculty. The board is smaller and I work more closely with them. That’s a different relationship. But I’m speaking about long-term faculty, perhaps some long-term donors and past board members. That’s something I think is completely addressable because of how much people love this place. But it’s a longer-term proposition than I realized.

What are some of the push-backs or objections that you’ve encountered, criticisms about the way the school was, maybe still is? It would be good to have a more specific idea.

Yeah, I understand. One of the wonderful things about the Art Institute is that it’s a place that really encourages independence and autonomy. But it’s hard for an institution to operate with any kind of intention and any kind of sense of progress if people aren’t working as a team. So how do you take the autonomous artist, or a group of autonomist artists, and ask them to stay autonomous as artists, but as professors and as part of the school to become a team? It would ordinarily be a difficult task. It’s even more difficult when some of those people don’t trust the way they’ve been asked to work as a team in the past, or don’t feel as though they were treated as team members. And I’m saying this with real respect for the last administration’s intentions and what they tried to achieve. But the result is obvious; that it didn’t really work. …

Chris Bratton was my predecessor as president. He is now president of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and I think his goals here were admirable. One goal was to bring in very prominent top leadership and greater diversity. For example, Chris brought in Okwui Enwezor who is a fabulous thinker and curator and internationally renowned person of African heritage. And he brought in Hou Hanru who is a Chinese-born, internationally renowned curator; and Renee Green who is now at MIT, an African American woman who greatly respected. … To do this in a short time was extraordinarily bold and courageous. The failure was in planning for it financially [and strategically]. Not bringing faculty and board along with his thinking, what he was trying to achieve—that created tensions. I don’t get much of a sense that he worked with those people that he brought in to strategize about how to include the people who had historically run and loved this place in bringing about the kinds of changes they wanted to make.

And so it was this sense on many people’s part that it was meant to be a complete cleavage and disjuncture and cutting off of all that is historically important and valuable in order to start something entirely new. That’s why it failed. To not take this incredible asset and realize all of its value and then build upon that, and instead to think that you’re going to just throw that all away and start over again—at least in some people’s minds that’s what the approach was—I think that is not likely to succeed.

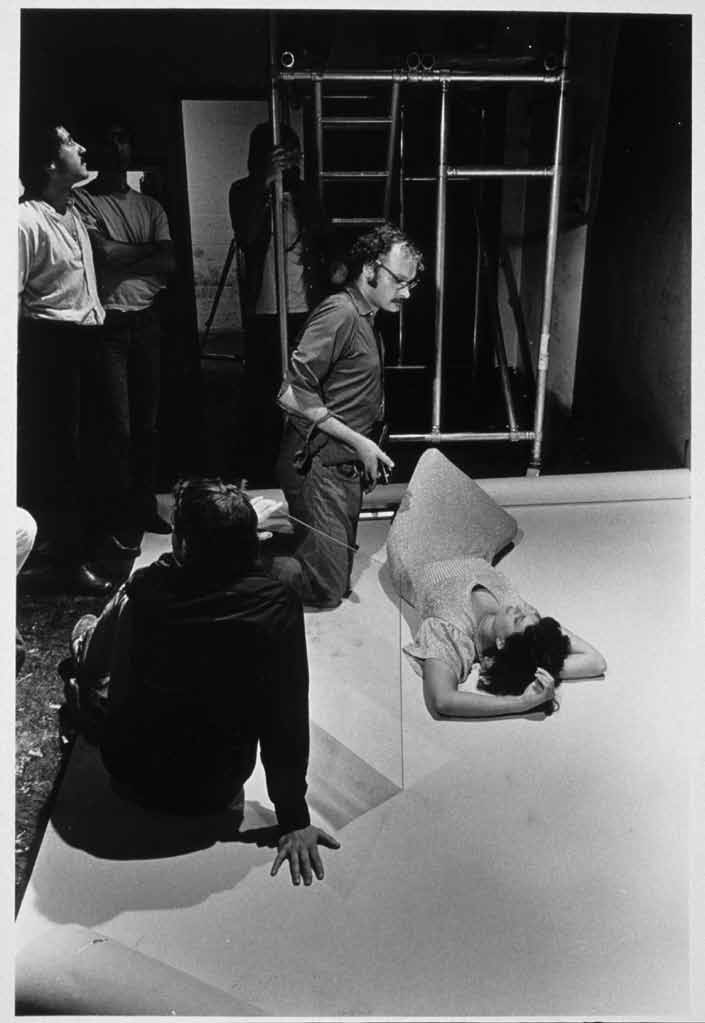

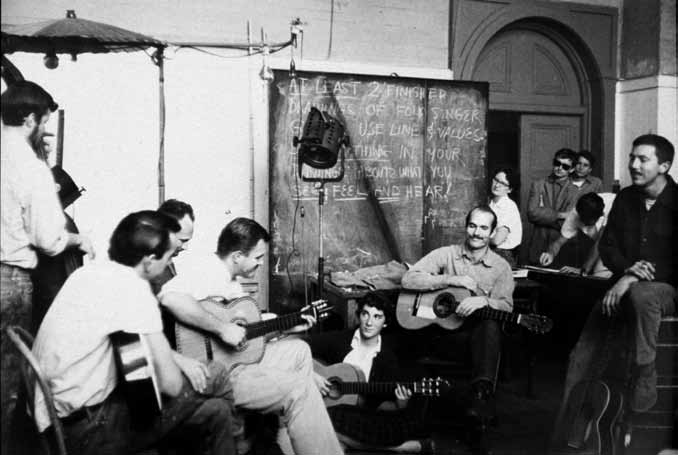

CSFA, c1958, William Morehouse class, with William T. Wiley, Wally Hedrick, Morehouse, Charlie Strong, “Draw what you...hear”. Courtesy of SFAI.

That nicely sets up my next question. It has to do with the notion of history and the responsibility and the training of an artist where modernism seemed to have taught that you need to clear out the old to bring in the new— pretty much what you described. I think that was happening here well before your arrival. Going back to the time after Douglas MacAgy and under Ernest Mundt when most of the super-star faculty left, like Clyfford Still, or were either fired or quit in protest. Hassel Smith, David Park, Elmer Bischoff.

Post-modernism is taking history as a tool and using the parts of it that are of value. It’s also trying to understand from the inside out what the various social structures, art practices, or whatever are really about and reflecting on them and reflecting back upon them. That’s where our understanding of art history matters.

But my question is how important is it to make sure knowledge of the past— of art history—is part of the training of artists. It seems to me many students, younger artists, don’t have a full sense of where they come from. The larger legacy they’ve inherited.

Well, I take your point that many people, when they’re just graduating, don’t know as much as people who have spent an entire career in the field. But I don’t agree with you that artists generally don’t know their past or don’t know art history. Virtually all of the really strong artists know a lot about history. They may pick and choose what they want to know and …

What generation are we talking about? I’m thinking of young artists, your students.

I’m saying that you have to learn over time. The artist who will succeed in reaching an audience, in making a difference, in exciting the art world or critics or museums will learn history because they need that as they develop. They might not feel that they need to become generalists. But I don’t know any artists who have real careers and solid exhibition records, critical response, that don’t pay attention to history.

Good. I’m just curious to know in what ways the Art Institute introduces to students their Bay Area predecessors, to create a sense of the rich local art history.

Well, actually, if you’re talking specifically about California art or San Francisco art, that’s actually an area of interest of mine, and of a number of our professors, that I think we’ll probably end up doing something. It can encourage the students. That’s my view. But you cannot graduate from here without a substantial amount of art history and broad critical understanding of the field.

That’s good.

So if you’re an undergraduate, you have to take English and writing. But there is Contemporary Practice, which is a foundation program of theory and ideas—what they call forming process and making history. And then you have art history requirements that include Global Art History, Modernity and Modernism, Contemporary Art Now, an art history elective, and a history of the major. There is a very broad liberal arts background here.

You’re here running a program devoted to teaching young artists. So you have your constituency. But what about you personally? Your personal relationship to artists.

There’s a very big difference between working at a museum and working with artists, and working at the Art Institute and working with artists. For one thing, all of our studio professors are working artists. It’s part of their job to continue to be working artists. And that gives me great satisfaction. And then, of course, with the students, even with their art history, still about 80 percent of their time is spent making art.

The biggest difference really is as a curator, as much as I visited studios and art galleries, for the most part I was dealing with fully formed ideas and works of art. You visit artists in whom you’re already interested. So you’re working with fully developed artists and works of art.

Here, you’re working with people through the process, which requires a very different kind of eye. And it’s exciting to me that I’m developing that different kind of eye very rapidly. You have to. It’s not judgment of this thing as a finished work but rather trying to understand the approach.

So it’s a different set of standards. And I don’t mean standards in terms of judgment particularly but what matters at this stage and what matters at that one.

Absolutely.

I don’t want to put you on the spot. But if you had to make choices in your life about the people you want to hang out with, how would you characterize that?

Hands down, if it was just about social life, it would be 100 percent creative people. No question in my mind. But I guess maybe another way to put it is that it’s the creative part of anybody that I’m interested in. And so when you have the time to be with artists, you’re being with people whose entire job it is to be creative, and that makes them more interesting than most of us who have only some creative aspect to what we do.

But anyway, for me and I gather for you, we started out not with any obvious direction pointed towards what we ended up doing, but we have somehow along the way found out how to live—or that you can live—the art life.

That’s a great, great gift, isn’t it? It really is.