Andrew McClintock: One of your first noted pieces created during your undergrad at Pomona College was a large outdoor sculpture that because of its physical nature ended up becoming interactive—can you please talk about this and if that helped point you towards starting more performative based works.

Chris Burden: The large outdoor sculptures were objects that people interacted with. I realized that the outdoor sculptures didn’t need to be that big to work, or to be part of a process, or to make an object that made you make an artwork. I didn’t need to make them that big to be clear about what I was trying to say…well I went from the outdoor sculptures I did in my undergraduate years to the graduate school exercise pieces, which were apparatuses that you had to use. Physically using the apparatus was the art. It was part of a long process, and ultimately when I did Five Day Locker Piece, I realized I didn’t have to make an object to do an action or a performance. I could actually use an already made object.

And just insert yourself into a situation with the object.

That was a big breakthrough because the objects that I made that were the catalyst to these physical activities.

Right, the Apparatus pieces?

Yes, those things became problematic because they were pretty nicely crafted, and people thought they were the artwork. When in fact, they weren’t.

Because it was more about the actual action in the performance?

Yes, those things were just the objects that enabled you to experience the artwork.

So, moving forward towards Five Day Locker Piece, was there an ‘a-ha’ moment where you’re like “I’m going to lock myself in a locker for…”

Well I had done this work at a place called F Space before then, called Being Photographed: Looking Out, Looking In and it was a three-part sort of installation. F Space was an industrial space in Santa Ana. Everybody who came in the gallery door was photographed, so there was a Polaroid picture of everyone who walked in the front door to see the show. In the middle of the space there was a platform that was made by two by fours and hung from chains about 18 inches from the ceiling. I had cut a hole in the roof and there was a scope with a metal eyepiece. You could climb a ladder and get on this wiggly platform, and lie on your back and look through the scope and you would see nothing but sky. So if a cloud went racing by, you would have this weird sensation of speed because that was your only reference. So that was the looking out. And these industrial units had these little bathrooms in the back corner with a sink and a little toilet. I sat in the bathroom, on the toilet seat cover, and in the door was a fish eye lens that was flipped around, so they could see me, but I couldn’t see them. So that was the looking in. I think in some ways that installation pre-dates…well, I did make the platform and stuff, but using the bathroom as a container was I think a predecessor to Five Day Locker Piece. In Five Day Locker Piece there was an ‘a-ha’ moment because I kept going back to the graduate galleries and looking at the space and thinking about being in a box and then I saw to the side, there was sort of a partition wall, which was originally a classroom, with an alcove with a bunch of lockers. And I went, ‘That’s it. Use the lockers, don’t make a box.’ I had solved the problem of people confusing the apparatuses of the exercise pieces as actual art objects. The apparatus was simply a tool that enabled you to execute the particular motion. The viewer executing the motion was the artwork, not the apparatus that enabled you to do it. So, to use a pre-made box instead of making one was a big breakthrough.

Chris Burden, photographed by Andrew McClintock.

So it seems like you continued that with White Light/White Heat where it was more than just making complex objects?

Yeah, but I did construct that platform. That was a construction. That was not originally part of the gallery, this high platform in the corner of the gallery.

But at the same time, it was a simpler construction compared to previous works from undergrad and early grad school.

Yeah, I think you’re right. Although when I thought about it, I thought people might think it was minimal art or some Robert Irwin, with light in the corner.

How did you feel about this interaction with the viewers, with the audience during these two isolation performances?

They were different. Five Day Locker Piece—people would come and talk, with the locker, like a confessional. I wouldn’t talk back, but they knew I was in there, or they believed I was in there. White Light/White Heat—people would come visit the gallery and I could hear them talking, I could kind of feel their energy, and I could also hear the staff during the day. I told my friends to come in and visit me and tell me stories, tell me what they did, but I wouldn’t be able to talk back to them. Five Day Locker Piece was done in this relatively hidden graduate student art gallery on the UCI Campus, tucked away in some classrooms. But White Light/White Heat at the Ronald Feldman Gallery was on 74th Street in Manhattan, with a lot of foot traffic. It was a more public space, UCI was more intimate. None of my friends were really able to come and talk to a shelf (laughs); it’s very hard to do. The interaction with the public was different there. The only person who was able to have a direct conversation with me was the gallery owner, Ronald Feldman. He would come in and give me a 5 o’clock daily report of who had been in. Even though I didn’t talk to them, I could feel the people’s energy. Half of the people didn’t believe that I was really there. I guess what I’m getting at is that it was a busy day and at the end of the day I was tired. Which was weird. I was basically in some sense, an audio voyeur.

Chris Burden, Apparatus Sculpture, 1969-70.

So early documentation of your performances are very raw. It seems like the descriptions you write; in an almost narrative sense give more insight to the piece. Was this part of it? Or was that the documentation an afterthought?

No, the documentation was always part of the process. I did performances, I had them photographed, I had the photographs developed, and I would look at them and try to pick out one iconic image. After the one iconic image was chosen, I would write just the facts in text. That was intentional. I didn’t really want to get into what I was feeling, what I was thinking, why, how does this connect to the greater cosmos. I also think that’s part of being trained as a minimalist – to try to get to the essence, just a reporting of what happened.

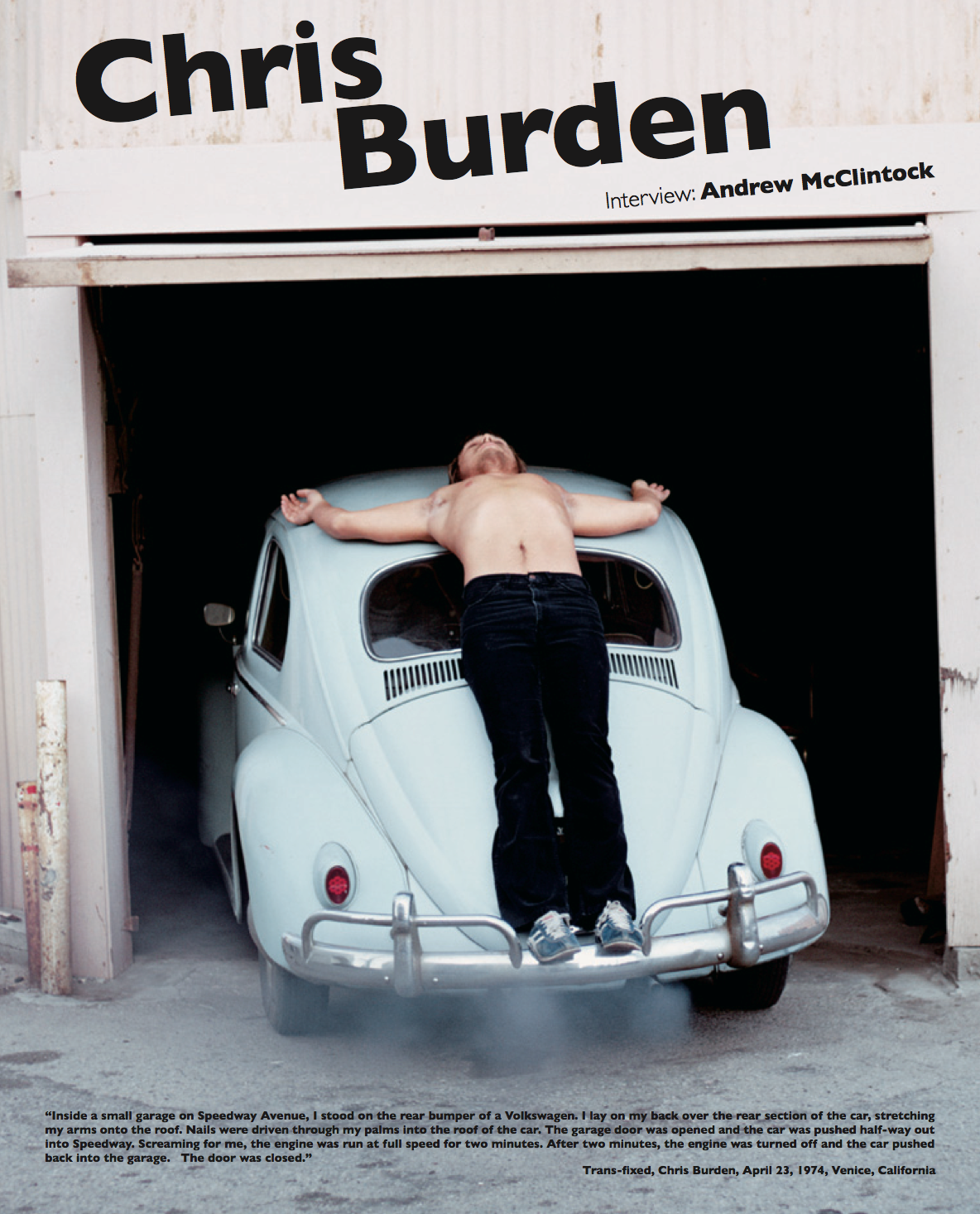

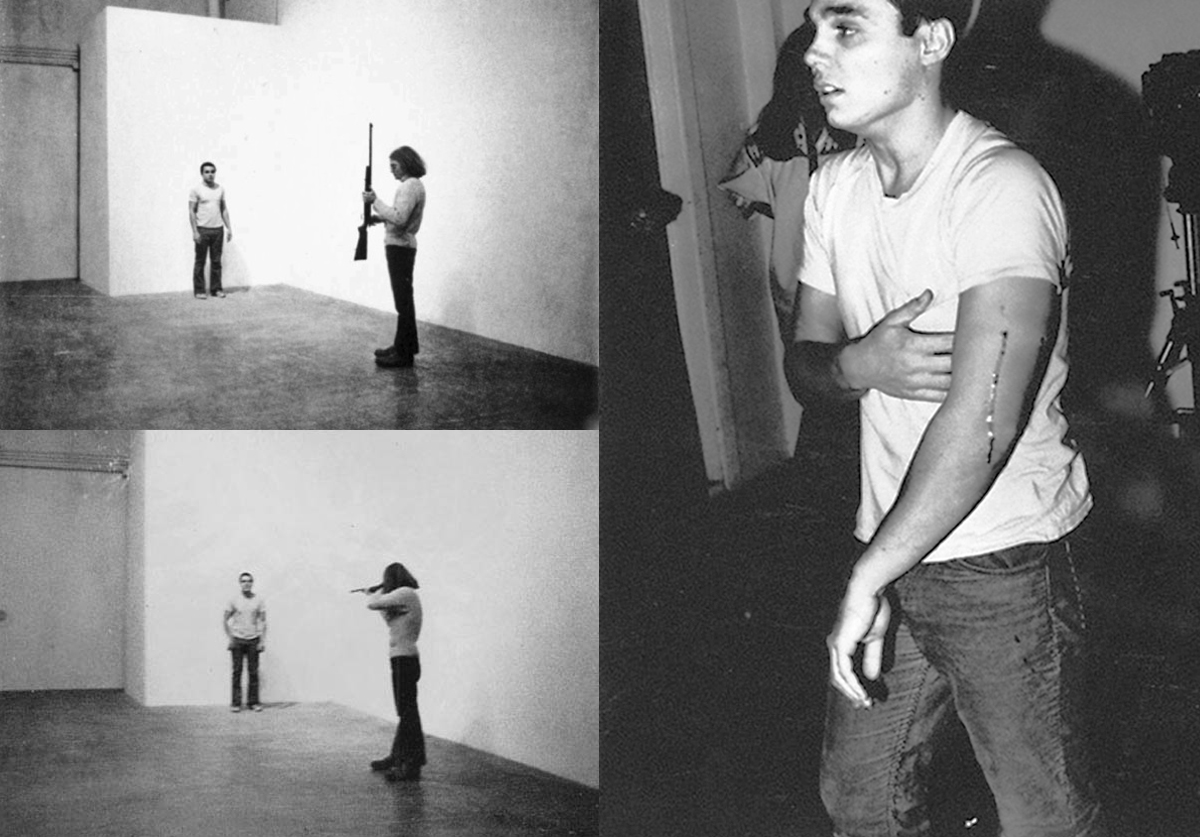

Let’s talk about the Shoot piece, it seems that and Trans-fixed are two of your more well known earlier performances. What was going through your mind when you had that gun barrel kind of pointed at you?

Well, I was hoping he wouldn’t miss (laughs). I was trying to do this very structured clean, precise thing. We had practiced some – he had practiced shooting near me, and I was trying to get him just to graze my arm, to actually nick it. My fear was he would err on the side of safety and would miss. But then it became kind of murky, if he misses – does he try again, is it over, is that it? You know what I mean, it becomes…I don’t know, and I don’t have an answer to that because it didn’t happen. (Laughs) I don’t know, we’ll try again tomorrow night.

Were people in the audience shocked that he actually shot you?

Well, it was a small audience, there were people that knew me, and I had invited them. I think they went along with the idea that he was going to be so precise that he would basically just scratch my arm. That was the original construction of the performances; it wasn’t supposed to be a bullet hole, it was supposed to be a scratch. Then there was this kind of weird question – if you’re in combat and somebody grazes your scalp, are you shot? Technically, yes. So that’s how I intended for it to be but of course it could have gone either way. And luckily he didn’t miss. So that’s actually what I was thinking about, I hope this guy doesn’t miss (laughs).

Chris Burden, Shoot, November 19, 1971. F Space, Santa Ana, California.

I mean that seems like an unnatural thought at that point.

Which is a weird, right? Because it’s contrary too. I was trying to make an artwork. If he missed it was going to be worse than if he didn’t.

So, while you were getting your MFA from UC Irvine, you spent some time up in San Francisco?

Well, I met Tom Marioni and I’m not sure if I met him in San Francisco. I think I met him through Barbara Smith. He had come down to Orange County to visit her, and we met. I think at that point he invited me up to do something at his museum, and that’s when I did my performance I Became a Secret Hippy.

So that piece was up at his Museum of Conceptual Art?

Right, his first museum.

Were you able to make any observations on how the scene was up here at that time?

Well, it was of interest to me because I was doing performances and actions and met a whole bunch of people up there that were of interest to me, artistically. Howard Fried, Terry Fox, Paul Kos…A whole bunch of people.

So after that piece did you revisit up in San Francisco?

Yeah, I would come up periodically for different occasions. I taught up in San Francisco, at the Art Institute for one semester. I did Fire Roll for the exhibition All Night Performance at the Museum of Conceptual in 1973, and both my performances Sculpture in Three Parts, in 1974, and Garcon!, in 1976 at the Hansen-Fuller Gallery. And you know I’ve done work with his current wife, at Crown Point Press. But, I haven’t been up there lately.

Okay, so towards the close of the 70’s it seemed like a lot more people were doing performance art and trying to be totally crazy and outrageous in a who could top who environment. Is that one of the reasons why you phased that work out in a sense and moved in a different direction?

No, it wasn’t about other people, really. It was more that I’d done so many performances, and partially it was because of the press. It was just so outrageous. I almost didn’t do the Trans-fixed piece, because I knew how it would be reinterpreted through mass media. In fact there’s an article in “OUI” Magazine or something where they had a double page spread and I’m on an orange bug. It’s an illustration, an artist’s concept. I’m one-handed, the car’s orange, I’ve got a huge hand with a giant nail in it. So I already knew by the mid-70’s, that anything I did that I thought was kind of clear and precise would be spun out of control by mass media. So I already was thinking of doing other things and I think the B-Car was the beginning of a big change in my work, because I went back to making things. I think a lot of the objects that came after the performances were actually performative in themselves. The B-Car became in some sense the surrogate for me.

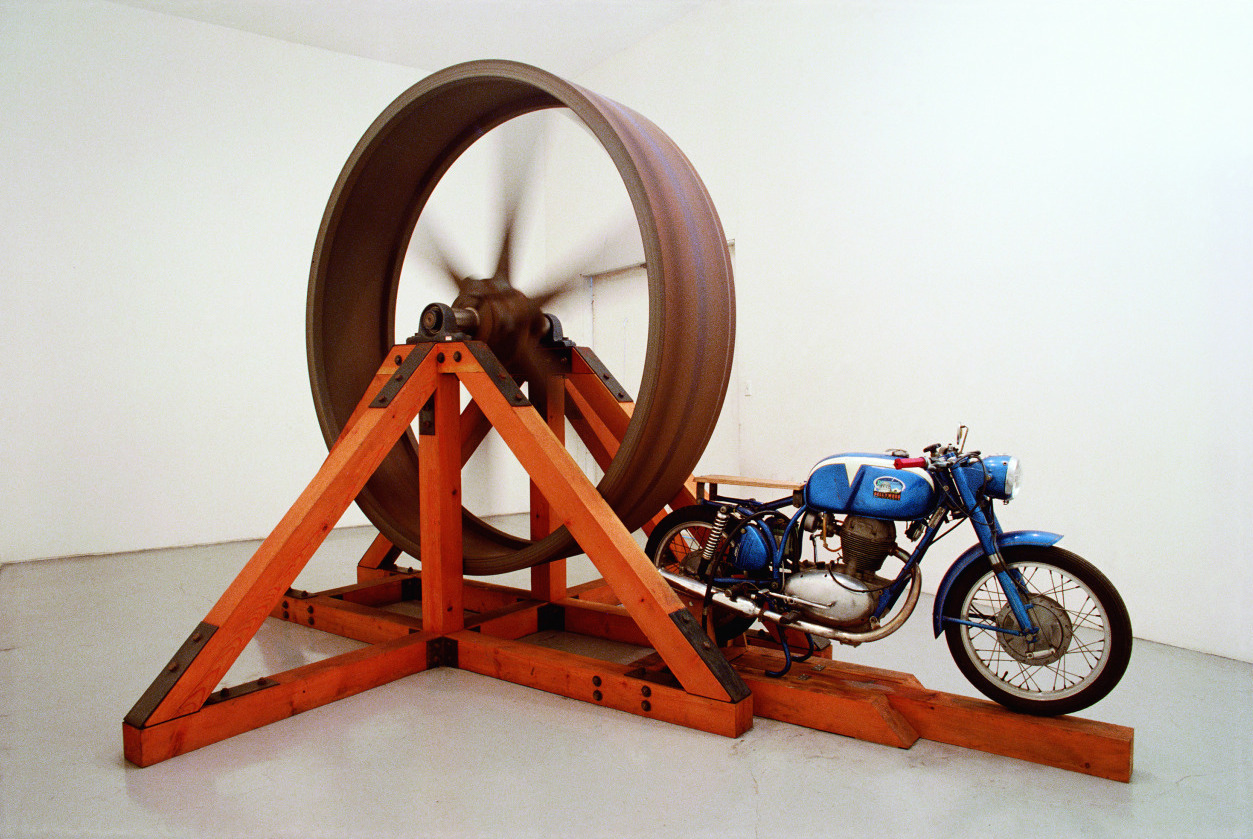

Chris Burden, The Big Wheel, 1979. 3-ton, 8-foot diameter cast iron flywheel powered by a 1968 Benelli 250cc motorcycle.

It makes sense; it’s kind of like full circle.

In “Big Wheel”, the motorcycle is obviously performative. I do not physically have to operate the motorcycle. It’s a performative work in a certain sense that someone has to get on the motorcycle and drive it for it to happen.

So you’ve been represented by Gagosian Gallery since 1991, and I’ve always been very interested, you know they’ve put on some pretty amazing shows. What’s the process of working with a gallery that’s able to facilitate the caliber of work that you’re trying to do? Compared to working with other galleries what’s your experience with Gagosian?

It’s a big gallery and there are pluses and minuses. The pluses are they can help you realize bigger projects and provide a client base. The minus is you’re competing with forty of fifty other artists. But every gallery is different, galleries change, artist’s change. So working with Gagosian has been fine, they’ve helped me realize a lot of things. A lot of things I’ve realized on my own. Larry Gagosian has a vision, and he does do amazing projects. So if you can catch some of the salmon swimming upstream, all the better. (laughs).

So moving on to pieces like What My Dad Gave Me, Beam Drop, and The Flying Steamroller, they seem great because it seems like you’re having a lot of fun with them. It’s kind of like the idea of every kid’s fantasy taken to a whole new extreme.

Yeah, I see what you’re saying. I don’t think I was fascinated with big trucks as a kid; I wasn’t a truck nut or a construction nut and I didn’t build huge Erector sets or big Lego things. I had a train set, but my Dad built most of it. I used to make things out of cardboard and stuff with my brother.

But Is using those materials meant to kind of touch on kid’s fantasies?

Yeah, it is in a certain sense. Like, What My Dad Gave Me uses a million Erector parts. Of course no kid is going to have a million Erector parts, right? They could fantasize about something like that but they just couldn’t carry it off. So it’s a little bit like fulfilling, not my childhood fantasies, but every child’s fantasies. Which is different. Kid have great imaginations and great fantasies, they just don’t have the skill set and the resources to pull off their fantasies. But I do (laughs). It feels good, because it feels like I’m completing something that was left kind of…the fantasy of the guy who invented the Erector Set, A.C. Gilbert created those metal construction kits after watching all those buildings go up in Manhattan. He wanted to devise a toy building system that could mimic the excitement of seeing all these structures go up. I used the Erector system, albeit I did reproduce the parts out of stainless steel, basically the same mechanical system in a different metal, to build a toy building that is as tall as a five-story building, it becomes very bizarre. It comes full circle, again.

So I wanted to ask you about subversive qualities in your work, especially in Through the Night Softly and Poem for L.A.—if you were driven by any political means just to try to speak out against the status quo?

Well, yeah. It’s important to put it in historical perspective because now everybody has access to overindulge in media. But in those days, there were just basically the three major national networks, some local stations and some education stations. It was very clear that the media only came at you; you know what I’m saying? You were only a receiver; you couldn’t be a generator really. They had all the power, so how do you get on TV? I kept thinking about it and I thought, ah yes, the good old American way. Just buy the time. If you buy the time, it’s your time. I found out later that’s not entirely true, there are some rules and regulations. A private individual cannot advertise on television, it’s an FCC law. But if there is a connection to a business, of course you can, because you’re advertising a product and it’s for commerce. So that in a fact was a problem when I placed the first ad. I walked in and made an appointment with a salesman and he said ‘Well you don’t have an account, so you have to pay in advance.’ So I bought those minutes in advance and had this slot for a certain amount of money. At some point they took my commercial off the air because the station manager saw it playing. I had the fantastic joy of calling them up and telling them that they were in breach of contract and I was going to sue their ass unless they did something about it. They thought about it a while and then they played my commercial extra times to appease me. I have to say there was a tremendous feeling, like a David and Goliath thing. The station manager fired the salesman that took my money, you can’t take someone’s money and not deliver the goods, you know? So that part of it became interesting to me, too. When I did some later commercials, such as Full Financial Disclosure, I got smart and I went to a booking agent. If you go through the legitimate channels, then you don’t have problems.

I feel like even today, with all the violence we’re bombarded with, if one saw a commercial with someone crawling through glass—

Yeah, it was abstract, you have to understand it was black and white, it wasn’t color. It was just this weird thing. I don’t even think it looked like glass; it just looked like this strange abstraction. The glass reads like stars, and I was sort of rocking back and forth. I did another commercial, Chris Burden Promo. Actually Tom Marioni told me if you ask any man on the street, five names will come up as the best known artists. I made a commercial, and my name of course is the last one. It said paid for by Chris Burden. I was trying to advertise myself to a museum director’s conference in LA. Then I played it in New York and I don’t know how I justified it there, but I bought commercial time on the “Saturday Night Live” show, like a regular sponsor. For people who were watching “SNL”, they probably thought I was part of the show.

What year was that?

The late 70’s. So that was a funny crossover. It was subversive in a certain sense, but it was fun. It was a great feeling of power; when I was driving around LA at night and you’d see this ocean of lights and realize man, tens of thousands of people have seen my ad tonight and they don’t have a choice. It’s a funny feeling. And people would come up to me after I did one. In Poem for L.A., people actually recognized me in the supermarket and would ask me what it was about. That was a little scary.

I could be wrong on quoting you on this or just paraphrasing what you said… you’ve mentioned that you believe artists who were making cutting edge art at the beginning of the last century, would have moved in the direction of performance and conceptually driven work.

Well, I think I said that. I’m not sure that it’s a 100% true, I think I said that because when I would give lectures sometimes people would be really hostile and say how can you call this art and what do you think you’re doing, and how does this fit in with the grand traditions? When it’s all said and done, I still think you can make cutting edge art using “safer mediums.” I just think there’s a great sort of Diaspora of genres that artists can work in, but maybe not. Maybe Picasso would not have made videos. But who knows? I certainly think the Dadaists would have used new mediums. No question in my mind about that. Again I think I was just trying to respond to super conservative talk show kind of conservatism.

In the art world?

No, in the real world. I was on a regular TV talk show and discussing my recent sculpture Beam Drop, and getting questions like ‘how can you call what you do art? Art is the kind of work they made in Renaissance times… that is real art’ Well maybe if those Renaissance guys were alive today they would be dropping beams… who knows.

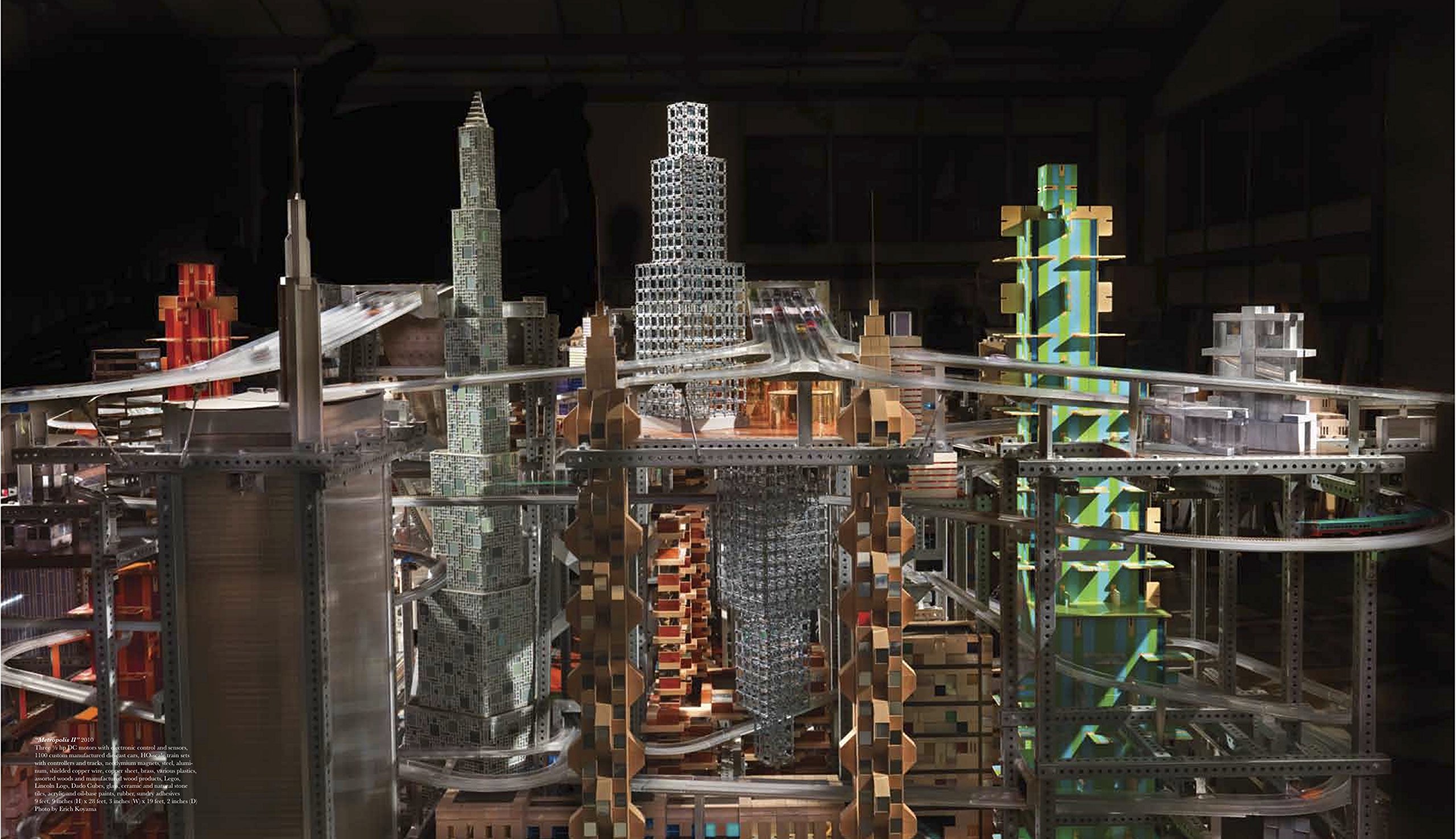

Chris Burden, Metropolis II, 2010.

So you’ve been working on Metropolis II for about four years now?

Yeah, actually my part is finished; it’s being reinstalled at the LA County Museum as we speak. It should open sometime this late Fall.

It’s pretty fascinating how it captures the energy of a city because it’s so large and involves all these miniature representations of transportation and technology but they become real.

Well I think there are a couple things. It isn’t that large, there are much larger sculptures in the world. In terms of a footprint it’s 20 by 30 feet, but it is a frenetic beehive of activity. The audio level is really high because you have 1100 cars circulating through the system and 13 trains. It is also anxiety provoking to some extent, because of the audio level and the visual—you try to watch anything and you can’t because it’s going so fast. You can’t watch one single car go through the whole system. It’s the frenetic level activity and sound that actually produces a certain level of anxiety and tension in the viewer.

You were a professor at UCLA for many years. But you left due a controversy with a student who was trying to do a performance.

It was a grad student who did a performance in another professor’s class. I was actually in Europe. Basically, I wasn’t there so this is all hearsay. There was a class of about 30 students and they were all supposed to do a performance, each one. They sat in a circle and one student advised the others that his performance could be dangerous and that they should move their chairs away from him. He took a gun, a handgun, a revolver, out of a paper bag, held up two bullets, put one of them in the chamber, spun the chamber, held the gun to his head, and cocked and pulled the trigger. And it didn’t go off. Then he ran outside into the dark—this was at night—and the class heard the gun go off. The students were all freaked out because they thought he committed suicide out there. I mean, nobody wanted to go out and see him. About ten minutes later he came in and pandemonium broke loose. The students were hysterical and crying, and they were happy he was alive. When I returned from Europe I got a call from the Chairwoman of the Art Department and long story short, the university decided to not throw the kid out of school. My wife and I said, you know what, we can’t work here anymore. Because when you’re school you have responsibilities. We’re all in this community and there are rules and regulations—I can’t swear, I can’t say that anybody’s hair is too curly, can’t abuse staff, you know its part of civil university life. So if you want to do really extreme art, you have to quit being a student. Go downtown to your loft and do whatever you want. You can’t hide in the bosom of the university. So the fact that the University refused to expel the kid, I thought you know, you guys are making a grievous error. They asked what did I expect since I had done the performance Shoot? Well, I was not a student when I did Shoot.

But that’s not what it was about when you were doing it either.

No, and I say green and orange can be edgy. I think when you bring this up; I think you’re alluding to the fact that there is different motivation now.

It’s sort of inherent in our society at this point.

Yeah, it’s sort of a trickle down of Jackass. People want to be famous for 15 minutes. And I thought in a certain sense, this is actually abusive to me. So I didn’t teach there anymore. I taught there long enough anyway. But it was more that the University basically defended the student and blamed me. They didn’t come out and say it but it was obvious. They didn’t kick him out, he said it was a wooden gun, he carved it and he lied. Everybody believed him. That’s the story on that.

So I guess to wrap it up, your wife is also a well-established artist. Do you two ever collaborate on any work?

We did and it was so disastrous. We did a piece together at 80 London Street in the early 80’s or mid 80’s. Who’s the critic up there, Kenneth Baker?

Yes.

He attributed the whole thing to me and she was never mentioned. We did a subsequent piece in Los Angeles which was sort of a grand diversion of that, but we separated it completely. So she did her parts, and I built a lighting system that was generated with water. Again, because I was a better-known artist, I got the review. So we just decided it was a bad idea, and we don’t do that anymore.

This interview was selected from Issue 7 of SFAQ.