Uwe Frank Laysiepen, known as Ulay, is unarguably one of the foremost photographers and performance artists of our time. However, although critically acclaimed, until recently his pioneering work has remained largely unknown; his forty-five year contribution to art history often reduced to a focused period during which he famously collaborated with Marina Abramović. Today his oeuvre seems finally to be on the verge of garnering more universal recognition with a comprehensive monograph just published1, his first gallery representation, and a recently premiered, and highly lauded, documentary2 of his successful battle against cancer making the rounds of the independent film circuits.

In this documentary Dutch curator Ann Demeester refers to a film by contemporary Norwegian artist Lene Berg, in which the protagonist mispronounces the word charismatic as “charis-mythic,” a term she in turn uses to characterize Ulay. Certainly it relays both his undeniable charm and the many striking turns in his life story, beginning with his birth. Ulay was born in a bomb shelter during a 1943 air raid on the steel-manufacturing town of Solingen, in the populous German region of North-Rhine Westphalia. His father, an officer in the Wehrmacht, served in and survived both world wars, brutally compromising his health and dying prematurely in 1956, when his son was thirteen. Unable to cope with this loss, Ulay’s mother for all intents and purposes abandoned him two years later, effectively orphaning the teenager. Ulay has subsequently claimed this moment was “liberating,” and despite the deeper traces it undoubtedly left, he went on to succeed in his early years, starting a profitable commercial photography lab. At age twenty-one he found himself with a wife and a child, living proof of the German “Wiederaufbau” (or post-war economic boom)—a successful entrepreneur, but not a particularly happy one.

In 1994, Thomas McEvilley published Ulay: The First Act / Der Erste Akt—an extended conversation with the artist interspersed by the author’s own musings about and interpretations of Ulay’s solo work to date. His subject’s career as an artist had in fact begun twenty-six years earlier in Amsterdam in 1969 to be precise. A visit there in 1968 had sign-posted a different kind of “liberation.” The city pulsed with the possibility for radical change, fueled by the counter-cultural energy of the Provos and student protests and an active red-light district and drug trade. Unsettled and electrified, Ulay cut the ties to his family and relocated to the Netherlands. Beyond escaping from the suffocation of the bourgeois norms of German society, he was in search of self-knowledge. He began by taking up the camera3, which allowed him to document and access his new environment, its architecture and inhabitants. The pictures he took are remarkable. At the time, much of Amsterdam’s life seemed to be conducted on the streets, and Ulay was there to photograph the students, protesters, sex workers, drag queens, and others who made up its diverse demographic. His portraits and crowd shots exude excitement and empathy, solidarity, and amazement. His architectural images have the determination and ambition of the Bechers’ serial project, but their protagonists—the city’s grimy terraces and dwellings—glower and throb with the intensity of Kippenberger’s Psychobuildings.

Ulay also turned the camera on himself, authoring a complex autobiographical visual essay titled Renais sense (re birth). World War II and its aftermath had shattered any sense of German national identity. The revelations of Nazi atrocities, as well as the urban destruction and post-war occupation by the Allied Forces, inflicted grievous psychological damage on individuals, coloring every aspect of the country’s socio-political and cultural life. Enmeshed from birth in this destructive narrative, and unmoored by the dispersal of his family, Ulay’s quest for rebirth was both personal and political. But, it was played out at a remove and in private, in an extraordinarily fertile period of production during the years 1969 to 1975.

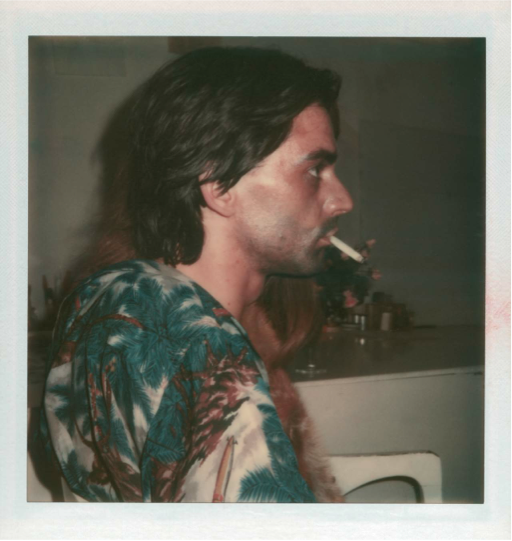

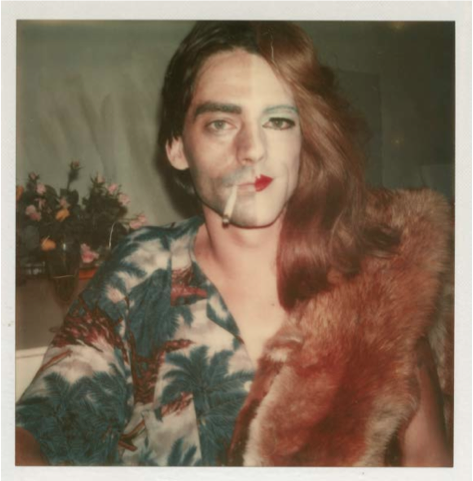

The numerous discrete series that comprise this extensive body of work depict the artist in a dizzying variety of situations and scenarios. They can be divided roughly into two genres: in one, Ulay uses props to stage situations; in the other, it is his body that becomes a prop on which situations are staged. At times an energetic cross-dresser capering on the beach (Dunes, 1973), at others a Nijinsky-like faun writhing through the woods (Elf, 1974), Ulay exudes a sensual, saturnine delight throughout most of the former category. He is perhaps at his most beguiling and disquieting in the images from the series S/he (1973–74). Often borrowing techniques and tropes from Amsterdam’s transvestite community, Ulay presents himself here as a vertically divided persona: half bewigged and in drag; half louche and stubbly male. Throughout the staggering variety of transformations he remains recognizably himself. The characters he presents are expressions of an interior truth, rather than props to catalyze an alternate reality. They appeal because they convincingly seem to represent facets of the artist’s personality, documenting them for analysis at a later stage. They are both mirror and reflection.

S-he, 1973-74. Auto polaroid. Courtesy of the artist.

S-he, 1973-74. Auto polaroid. Courtesy of the artist.

Less easy to behold are the photographs that show him cutting, pinning, pulling, and scraping his body mercilessly. Self-mutilation, drunkenness, and hints of bondage characterize the bleaker images and hint at real-life rather than constructed situations. Bene Agere (In Her Shoes)(1974), for example, shows Ulay processing the departure of a lover by literally trying to put himself in her shoes. Using a utility knife he traces a bloody outline of her ankle boot onto his foot. Another even more disturbing work is GEN.E.T.RATION ULTIMA RATIO (1972), which documents the excision of a tattooed square of skin from the artist’s forearm, and its replacement with skin grafted from his thigh. Recalling Orlan, and later Stelarc, the gesture most clearly portended an ambivalent relationship with pain. Overall these photographs document and establish the terms of use for his body as a medium as well as a vocabulary of endurance and self-exposure.

![Bene Agere [In Her Shoes], 1974. Auto polaroid. Courtesy of the artist.](https://www.sfaq.us/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Screen-Shot-2015-03-23-at-5.47.48-PM.png)

Bene Agere [In Her Shoes], 1974. Auto polaroid. Courtesy of the artist.

Individually and in their totality, the images are perplexing; theatrical, yet convincing; tormented, yet uplifting; sexually provocative, yet guileless. Their urgency is conveyed in their volume and their immediacy enhanced by the use of Polaroid. Their formats reflect destabilization; many are collages or composites, while some are further fragmented through the use of mirrors and reflections. Although sharing the prevalent anti-aesthetic approach to photography, formally and conceptually Ulay’s work was quite unlike anything else that was being attempted at the time, a fact of which he was unaware. However, he had by now realized that he identified as an artist.

At an earlier stage when he had felt the need for further theoretical and historical education he had followed his friend, German artist Jürgen Klauke, to Cologne’s Kunstakademie.4 It was during his art school years that he began signing himself Ulay, as shorthand for his lengthy name. The moniker stuck. (Interestingly, and pleasingly to the artist, “ulay” is the Hebrew word for “perhaps.”) At the same time as naming his artistic persona, he began laying the groundwork for collaborative practice. Although he remained the photographer and more often than not the director, he shared the stage with Klauke, as well as a number of other friends and lovers. A photo project from 1975 (Retouching Bruises) alternately pictures Ulay and his emaciated lover, bruises marking their bodies, and purple thumbprints highlighting the injuries on the prints themselves. The wordplay draws on photographic terminology, but the images are not tampered with; the model was anorexic, the bruises on both bodies real. Occasionally accused of trickery, Ulay is keen to underscore that his effects may be achieved through process, but never post-production manipulation.

Retouching bruises, 1975. Polaroid. Courtesy of the artist.

Performance curator RoseLee Goldberg has retroactively coined the term “performative photography” to classify Ulay’s photos from this period, acknowledging his creation of a new category. The term distinguishes them from documents of performance—itself then in its infancy. This distinction is important: Ulay does not consider himself a photographer, but rather an artist who employs photography as a medium.

At the time, however, the images were misunderstood. Or at least, that is how Ulay experienced the response to his first exhibition of the “personal” Polaroids at Galerie Seriaale in Amsterdam in 1974. The installation Ulay conceived for The Artist is Present made use of large metal sheets to line the wall of the gallery. Framed and mounted sequentially, Polaroid after Polaroid lined the slabs creating a storyboarded narrative that mimicked the frames in a reel of film. This conceit gave the images substance at the same time as the slabs provided both armor and support for the artist’s revelations. Unfortunately, display and content proved too sensational to allow deeper consideration about artistic intent. Disappointed by the responses he received, Ulay vowed never to exhibit these particular works again. (A promise he maintained for many years, although in recent times persistent curators such as Maria Rus Bojan have persuaded him otherwise and the images have once again started, thankfully, circulating through his monograph.)

Wrestling with his public presence and artistic career, Ulay became involved with the newly established De Appel. Founded in 1975 by Wies Smalls (collector and owner of Seriaale), the organization set out to offer a platform for the research and presentation of contemporary art. Realizing that if he could not dictate the reception of difficult work he could at least influence its framing and promotion, Ulay became active as a board member and program consultant for the organization. It was at his suggestion, then, that Marina Abramović was invited to appear at De Appel in December of 1975.

Although Ulay had followed Abramović’s career from afar, the artists met in person for the first time at the Amsterdam airport in 1975. It was a determining moment for both of them. Captivated by Abramović’s vitality, Ulay was entranced by her re-performance of Thomas Lips in front of a shaken audience on December 5, 1975. Devised for Galerie Krinzinger in Austria earlier that year, this performance has now been performed three times by Abramović and is considered one of her seminal works. The artist eats a kilo of honey, drinks a liter of wine, carves a five-point star on her stomach, and flagellates herself as a prelude to crucifixion on ice. Documenting Abramović’s progress through this inventory of masochism, Ulay realized that he had found the personification of the female other, or anima, he had been exploring in his photographs. The twin-like nature of their physical appearance was further enhanced by the discovery that they were born on the same day, November 30, albeit three years apart.

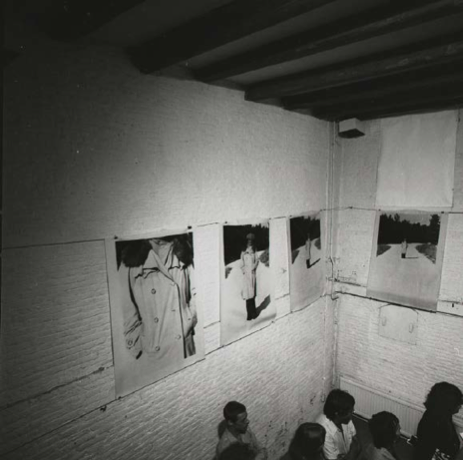

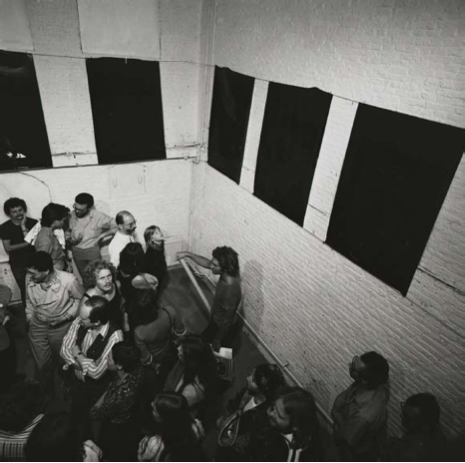

By all accounts, the meeting was significant for both artists and the times that followed were happy, intense, and productive. Before they could collaborate artistically, however, both had to consider the implications for their solo careers. Ulay had a number of public performances he wanted to undertake, one a series signaling the (as it turned out, temporary) end to his photographic work, and the other a dramatic intervention. Recently re-performed5, Fototot (“photo-death”) was a radical tri-partite action, one of the first to underscore the ephemerality of photography as a medium. For the first part, audiences were invited into the darkened space of De Appel. The lights were turned on revealing nine large photographic portraits of a veiled figure receding up a road. Unfixed and mounted high on the gallery walls, the photos started fading to black 30 seconds after being exposed to the light. The variously bemused and anxious responses to this disappearance were photographed by Ulay and formed the subject of the second part. Entering the same space at a later date, visitors were confronted by a folder, invitingly placed on a table lit by a desklamp. As soon as it was opened, the contents of this folder, unfixed images of the first event, also evanesced. For the final part, staged at Beyer Galerie, in Wuppertal, Germany, Ulay kitted himself out with a crash helmet and strapped a large mirror to his front. Video documentation of the performance shows him swaying slightly under the weight of the glass pane, before kipping forward. The mirror shatters and the audience gasps. Ulay, however, is miraculously unharmed. Frustrating audience expectation, denying photography’s claim to memorialize, or even to reflect accurately the present, with this work Ulay signaled a new chapter in his practice. Photo was dead, long live the artist.

Fototot 1, 1976. Performance documentation from De Appel. Courtesy of the artist.

Fototot 1, 1976. Performance documentation from De Appel. Courtesy of the artist.

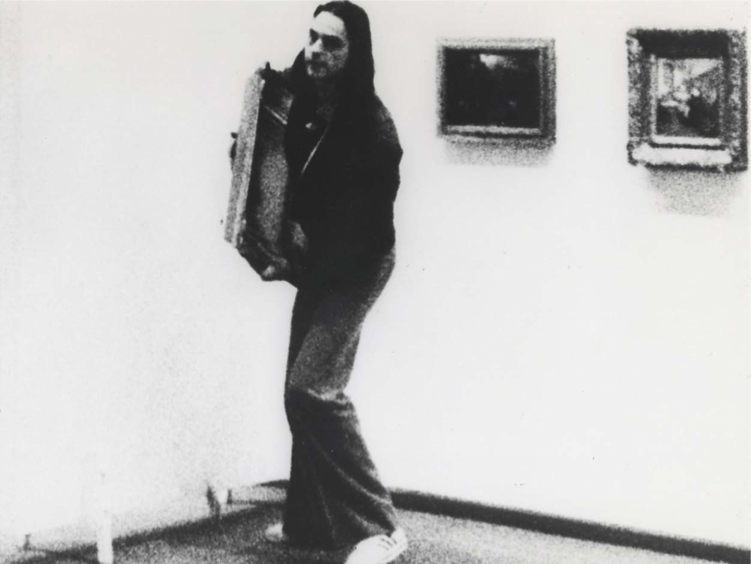

Once extricated from the shards, he was able to turn his attention to his final solo undertaking for a while—Action in 14 Predetermined Sequences: There is a Criminal Touch to Art. This stupendously daring and outrageously provocative action survives as a documentary film (viewable on Ubu.com). As described in the scripted instructions that are part of the piece, in December 1976 the artist entered the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, removed Carl Spitzweg’s painting Der Arme Poet (The Poor Poet, 1839) from the gallery walls, and, clutching it under his arm, sprinted out of a fire exit with the security guards in pursuit. The theft of this national treasure was not staged; it was as much a surprise to Ulay as to the guards that it succeeded. The work was destined for the wall of a Turkish Gastarbeiter (guest worker) family, in the city’s Kreuzberg district. After successfully hanging it there, Ulay called the gallery’s director to confess and let him know where he could find the painting. Outraged national media responses and a trial followed, but Ulay again emerged unscathed, despite a court summons and a mild sentence (36 days in prison, which he never served, instead paying a small fine). The grainy black and white documentation of this action—a composite that includes film from a small handheld—is lent menace and a sense of inevitability by the accompanying sound of an unplugged amp. The insistent, low, rhythmic hum heightens the tension and romance of this quixotic denial of the rights of its immigrant labor force, this symbolic and actual violation of the boundaries of the art institution, art, and politics set the scene for the period of collaboration with Abramović—or Act II.

There is a Criminal Touch to Art, 1976. Film still from the Berlin action. Courtesy of the artist.

Despite the hardships that they endured due to their uncompromising pursuit of an ethical performative and collaborative practice, and their bitter break up, the years together are remembered fondly by both artists. The details of their peripatetic lifestyle during the early days are by now familiar—the five years spent living and traveling in a customized, but ultimately small, van, the struggles for survival: Abramović cooking, knitting, and selling sweaters to make money; Ulay managing mechanical repairs, their accounts, and bookings; and the performances in small venues for small fees and audiences. Their existence blurred the boundaries between art and life, and their practice drew on this ambiguity. The manifesto they devised early on to structure their collaboration enshrined this paradox. Titled “Art Vital,” it espoused:

No fixed living-space

Permanent movement

Direct contact

Local relation

Self-selection

Passing limitations

Taking risks

Mobile energy

No rehearsal

No predicted end

No repetition

“Permanent movement” and “taking risks” alone meant a continuous raising of the stakes. And while their ideas did not develop in a vacuum—Ulay cites in particular the works of Vito Acconci, Chris Burden, and Gina Pane as inspiration6—they did retain a discipline and specificity to their relationship that was compelling. Undeniably their chemistry was part of the draw.

As word spread of their performances, invitations to present their work multiplied. Their travel itinerary also intensified and they traveled increasingly farther afield. A disorienting but formative trip to the Australian outback lasted for longer than anticipated; Ulay wanted to stay, Abramović to return. Ultimately, their expectations proved irreconcilable and a work that was initially supposed to signal their permanent union instead marked its end. Taking place in 1988, The Great Wall Walk involved Ulay and Abramović starting at the east and west ends, respectively, of this monumental structure and walking its length. They met in the middle, on June 28, after three months of arduous trekking, with the sad realization that their partnership had run its course.

While it might not seem productive to attribute responsibility for either the break or the performances to one or other of the partners, it is true that an agreement signed by both in 1999 allows for works from 1976–80 to be credited Ulay/Abramović, whereas those from 1981–88 are credited Abramović/Ulay. The distinction is significant, if not always observed. It is true also that the later performances relied increasingly on the use of props and costumes (rather than nudity or everyday clothing) and on one occasion even took the form of an ensemble performance at a theater.

Much remains by way of documentation of the Relation Works, as the performances that the artists undertook during this time are collectively known. The early works in particular are indelibly etched in the performance canon. They have been handed down to us as a series of photographic vignettes—Ulay and Marina colliding headlong into each other (Relation in Space, 1976), or flanking a narrow doorway through which embarrassed visitors squeeze (Imponderabilia, 1977), or locked in an embrace, breathing each other’s exhalations to the point of collapse (Breathing In/Breathing Out, 1977). Abstracted from their contexts, these images function as powerful, absurdist metaphors for gender and relationship stereotypes. What is missing of course is everything else that made them so compelling as performances: audience, environment, energy, anticipation, the element of surprise, contemporaneity.

Both documents and the repertoire of the performances raise a number of issues related to ownership and (re)presentation. To quote Abramović, “Each of us brought a certain luggage—I brought a suitcase of performance, in his suitcase was photography.”7 The photographs, accordingly, were generated by Ulay, although they are infrequently credited to him. Using a tripod camera taped in place, a fixed angle, and focus all determined in advance, Ulay relied on an assistant to actually click the shutter at regular intervals. He art directed these shots, even if he did not physically take them himself.8 It was Ulay also who preserved the archive of these images, customizing a freezer box and filing cabinet to the interior of their van, for example, to preserve the films. (The idea came to him after reading about Chaplin’s successful preservation of his film reels.) Thus it was Ulay who orchestrated how these works were to live on in our imaginations.

It was also Ulay who scored the performance instructions. “We are standing naked in the entrance of the Museum . . .” begins the score for Imponderabilia, evincing an economy of words worthy of Beckett. It was Abramović, however, who resuscitated them, negating the terms of Art Vital (“no repetition”) by adapting and re-performing them as part of her personal repertoire. Originally taking place in off-beat locations (from Galerie H-Humanic in Graz to the Studenski Kulturni Center in Belgrade) in front of small audiences, it was shocking to see the works included in her 2010 retrospective at MoMA, New York. Decontextualized (no “local relation”) and institutionalized, their simple, potent directives were fulfilled by anonymous youths trained by Abramović (“no rehearsal”). For many, Ulay was present retroactively, through his communion with Abramović during her performance The Artist is Present (a title that could be considered an ironic homage in light of Ulay’s 1974 solo show). At the time of writing, a 3:38 minute video excerpt of the encounter posted on YouTube a year ago has garnered 8,825,342 views. Though one could attribute the numbers to Abramović’s publicity machinery, undoubtedly part of the appeal resides in the palpable tension and emotion flowing between the two artists, a warmer echo of Night Sea Crossing (1981–87), one of their seminal durational performances.

It’s a problem raised not only by this partnership, or by these performances. We can think of the implications of exhibiting or recreating Fluxus scores, for example, or Kaprow’s Happenings, or even the bloody antics of the Vienna Actionists. We imagine the shock value of a headless chicken running across the floor being endured by audiences similarly tolerant and educated in performance norms, but in fact these events were often spontaneous, random, and sparsely attended. Audience responses ranged from boredom to aggression and even on occasion to intervention, changing the nature of the event. If a performance is understood as the synthesis of a number of factors—biography, personality, time, place, audience—then a reenactment can never be anything but an emulation, however distinct or a/effective it becomes in its own right.

S-he, 1973-74. Auto polaroid. Courtesy of the artist.

While Ulay never completely retired his camera, he began using it again for artistic ends in 1984, co-producing with Abramović parallel bodies of photographic work. These were for the most part staged, individual portraits of the two artists. Appearing as silhouettes, shadows, or even marionette-like figures, they are ciphers rather than believable characters. It doesn’t take too great a leap of the imagination to see these as attempts to gain distance and reflect on the disconnect between self and artistic persona, as well as perhaps the status of this self within their artistic relationship.

It’s perhaps no surprise that the break up in 1988 was followed by a period of ten years in which neither artist had contact with the other. The beginning of Act III had to be marked by a hiatus. In Ulay’s case, equilibrium was provided by another relationship, marriage, and the birth of a daughter. For four years he focused on his new family. An invitation from the Polaroid headquarters in Boston, MA to work with their giant-format (80” x 40”) Polagram camera catalyzed the next phase of his career. If his earliest photos could be said to be self-portraits, and his subsequent ones portraits of a relationship, then the more recent ones can be understood as portrait of society, or of life in general, as viewed through the literal and personal lens of the artist. In this way, Ulay’s expansive, ongoing inquiry resembles Sigmar Polke’s (an artist he admires greatly) project to reflect life. Indeed, Ulay is insistent that art must derive from life, that it gains immediacy and authority purely from engaging with proximate and urgent issues, rather than constructed situations. It’s worth considering in this context that he has never had a studio, and that he continues to seek out his subject material in situ, whether out on the street or in the desert.

An unwavering political and ethical commitment and a keen sense of social justice inform this perspective. Espousing a multiplicity of causes, Ulay has used his art to help campaign for women’s rights in Morocco, to advocate for clean water in Ramallah, and to help save the elephants in Sri Lanka. An interest in the conservation and preservation of the world’s water supplies runs like a stream through the last twenty years of his practice, expressing itself in numerous bodies of work. In Water for the Dead, 1992, for instance, the light reflecting from a variety of glass containers is impressed on polagram prints. More recently, in 2010, cell-phone imagery from a trek in Patagonia documents a search for water sources. Ulay has even founded an institute called Nastati in Ljubljana with Slovenian graphic designer Lena Pislak (his partner for a number of years and wife since 2012). This is a self-styled “private institute for art projects and creative solutions” with the grand ambition of providing “local solutions to global problems,” developing a “universal language,” and providing a platform for ideas and education. Whether or not it is able to succeed in its ambitions remains to be seen; its existence, however, underscores his belief in the ability of art and artists to effect change.

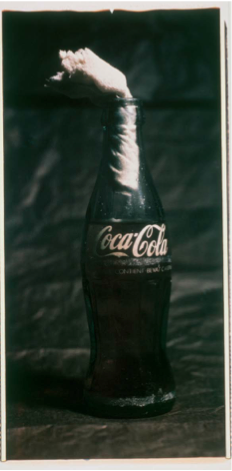

Molotov cocktail, 1992. Cant beat the Feeling, polaroid/polacolor, Boston. Courtesy of the artist.

Ulay’s oft-quoted maxim, “art without ethics is cosmetics,” is literalized in photographic projects from the nineties until today that continue to push the boundaries of both medium and content. His subjects primarily comprise the disenfranchised and marginalized, whether the homeless, the aged, African Americans, immigrant groups, the Australian aboriginals, or the mentally ill. To commemorate their centennial, the Vincent Van Gogh Institute for Psychiatry in Venray, the Netherlands, commissioned Ulay, who worked with patients to give workshops on photo reportage and postwar art. He also instructed them in basic photography, set up a studio with a digital camera on a tripod and a variety of props (objects, clothing etc.), and invited patients to create their own environment and take their own portraits over a three-week period. Sixteen participants contributed 260 moving and surreal ima es to the resulting book I Am Other. The Delusion: An Event About Art and Psychiatry (2002). One can see this project as an example of Ulay offering a personal set of tools for establishing identity to his subjects. In this way, and others, many of his projects remain collaborative keeping the boundaries between art and life, Ulay and his subjects, porous.

An appealing example of this blurring can be found in his educational strategies during his years as a professor of new media at the Hochschule für Gestaltung, Karslruhe in Germany (1998–2004). The “pedo-patetic” seminars he pioneered there may have been modeled somewhat on Plato’s academy, but owed more to his experience of Australian Aboriginal walkabouts and his belief in discipline and endurance. In search of self-knowledge, students and teacher would head off to the Black Forest for a week with nothing other than the clothes on their back, hunting for food and sleeping rough.

Act III, scene I saw Ulay reestablishing the terms of his personal practice. Scene II found him struggling against lymphoma. What happens in scene III, now that he’s back, remains to be seen. It’s clear that a determining factor will be the overtures that the art establishment is making to him—exhibition offers, gallery shows, an art market presence. In 2015 he plans to take up performance again, with an appearance at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Undoubtedly these factors will bring changes. It’s to be hoped, however, that the punk side of Ulay’s nature which has brought him this far, will never allow him to stop pushing the boundaries of his mediums, whether photography, the body, or life itself.

1) Maria Rus Bojan and Alessandro Cassin, Whispers: Ulay on Ulay, (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2014).

2) Project Cancer, 2013, directed by Damjan Kozole.

3) Ulay’s preferred camera remains the polaroid 980. His preference for Polaroid dating from his commercial laboratory days in Germany, resulted in an invitation from the company to function as one of their artists-at-large. This enlightened gesture on the company’s part extended to a number of artists who were given equipment and film to test and report back on, in exchange for a certain number of images and collaboration on projects (in Ulay’s case, a book of photographs of four cities: Amsterdam, London, New York and Berlin).

5) November 21, 2012. Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

6) In conversation with the author, Amsterdam, June 8, 2014.

7) Project Cancer, 2013

8) It is necessary to add that certain aspects of some works were restaged post-event if they were unsuccessfully documentation failed the first time around.