This is a companion piece to “Sprint Stories and the New Alchemy: Magic and Economy in Late Capitalism,” where I argued that in our moment of late capitalism, as we continue to exhaust raw materials refined for value-creation, we increasingly move towards abstract concepts as points of refinement, taking up rhetorics of value and worth that are structured by logics of alchemy. In this crucial and not always obvious way, we have shifted from a modernist outlook towards productivity and product—focused on mastering the natural world and everything in it—and into a logic that feels more arcane and supernatural. I’ll start where I left off with the Arthur C. Clarke quote that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” I want to suggest that the contemporary post-photograph has developed with, and offers an analogue to, the technologies that drive our magical-thinking contemporary economy—both in parallel and literally, through its digital turn and new networked, accelerated, encoded character—as well as to the logic of the alchemy-thinking economy itself (what I described in Sprint Stories as a detachment from the natural world and its laws), which this photography is well-placed to critique. Along the way, I am also sharing several images that I find useful to thinking through this relationship, whether as illustration or counterpoint.

Being post-

Post-photography, as explained by Robert Shore in his 2014 book, Post-Photography: The Artist with a Camera, covers a range of contemporary practices. The characteristics of a post-photograph include the use of found images often gathered from so-called “user-generated” collections of vernacular photographs on the Internet, like Flickr, Instagram, and Facebook.

Installation view at Pier 24 Photography of Erik Kessels, 24 HRS in Photos (2013). C-prints. Courtesy of Pier 24 Photography, San Francisco

To engage with this kind of photography is to consider the photograph as an analog to the current speed of culture and economy. As production accelerates, the relationship between users, consumers, and creators becomes an imperfect, restless one. Is this just a quickening of the speed of modernism, or an entirely different kind of velocity? Billions of digital images, deeply encoded and bursting with data, merge with the global economy of media, production, and consumption.

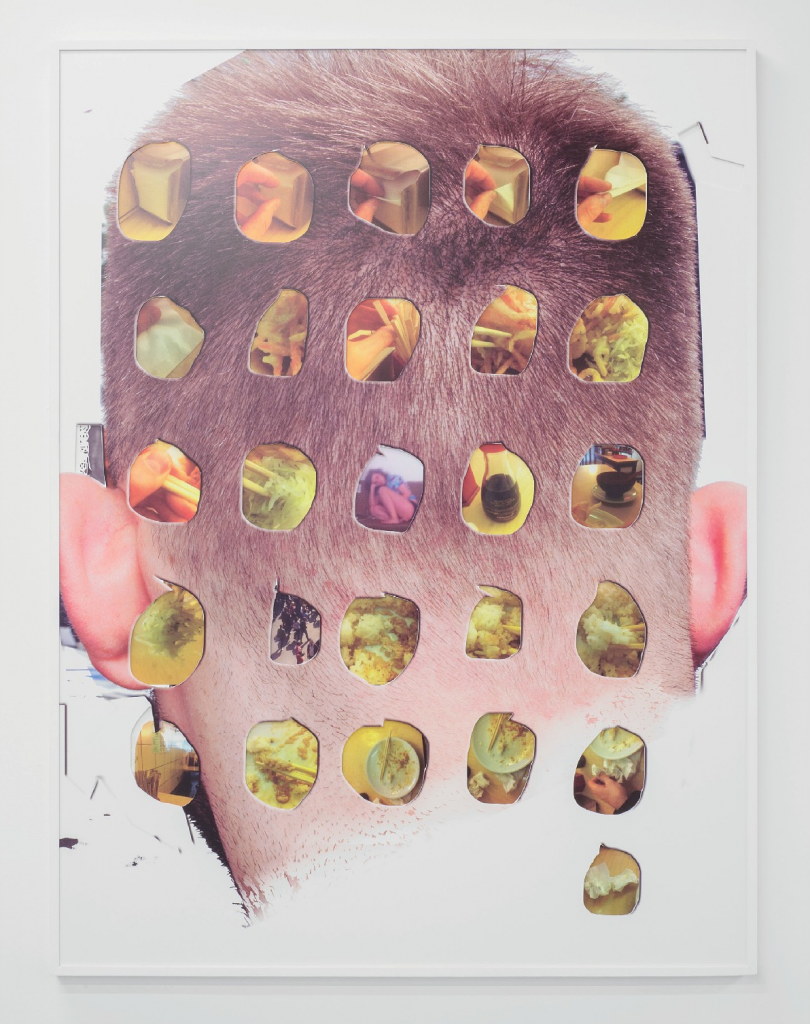

The other hallmark of post-photography is creating new images using methods associated with Photoshop (cutting, pasting, drawing, filtering). Post-photography is, in essence, post-Photoshop photography, historically and formally as well. Photographers must now make the active decision to use or otherwise confront Photoshop, other photo editing software/modeling software, and all the other technologies that now mitigate our everyday image production

Anne De Vries, Interface – Musashi, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

Magic tricks

In her book Photography is Magic, Charlotte Cotton calls this manipulated digital photography a type of “close-up magic:” both intimate and dexterous, gathering around it a crowd that follows its “flourishes and misdirections.”[1] There are tricks to be practiced, even seemingly unscripted “mistakes” to draw the eye. We are manipulated into first paying attention to the wrong things, the things that would distract us, like bright splotches of color covering an ugly cut-and-paste job. For Cotton, the moment of staging viewership, of letting the magical encounter unfold over and over, marks this kind of image. As Karin Bareman has put it, this kind of work shows its hand with the trick hiding in plain sight.

Lucas Blalock, Untitled (Crystalline Screw), 2009. Chromogenic print; 30 x 40 inches. Courtesy Ramiken Crucible and the artist.

No index, no book

But when value-finding looks increasingly like smoke and mirrors, the post-photograph is poised to expose the magical rhetoric in contemporary economics. Many of these “magical” practices are not just playing with perception enough to slow down the magic trick; they are also deeply critical and political, intervening in the magical thinking of our time by showing what happens when the image does not offer an indexical proof of anything. Just as the economy has been detached and abstracted from the tangible, so does this photography embody the condition of being unhinged from any foundation in the real.

Rhonda Holberton, Lilium Candidum, Rosa ‘Madame A. Meilland’, Alstroemeria (Night II), 2016-17. Archival Digital Print, Dimension Variable. Courtesy of CULT Exhibitions.

The machine will eat itself

Extraction from the real is an iterative process that eats its own tail, taking value when there is nothing left to remove: practices that repeat, regurgitate, rework the surface, and complicate patterns. The figure becomes its own ground as material concerns become self-imposed rules to follow until stalemate.

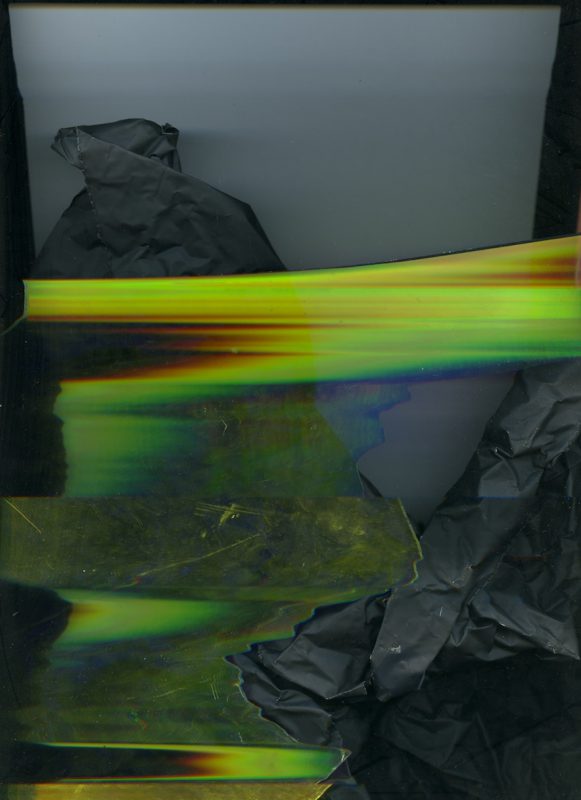

Walead Beshty, Fold (0°/90°/180°/270° directional light sources) June 13th 2008 Annandale-On-Hudson, New York, Foma Multigrade Fiber, 2008. Courtesy the artist and Wallspace, New York.

Abstraction, algorithm

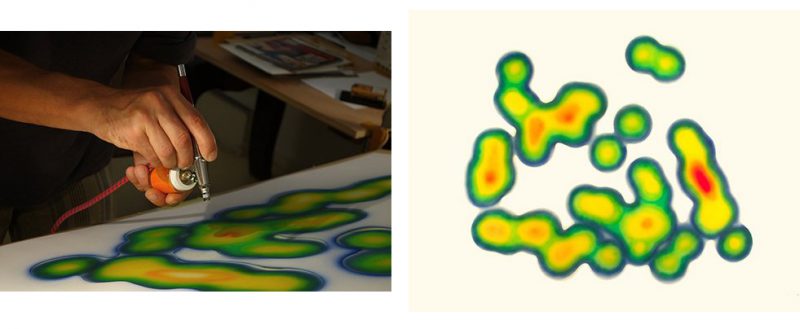

In the contemporary economy, this iteration can involve real objects and “real” photography, or it can operate in the realm of user-generated social media photography: as a source of valuable data. As with software, so with the “softimage,” as Ingrid Hoelzl has articulated it, our images mirror our systems softening, stretching their limbs, as eager to take up data to alter themselves as to create it.

Julien Prévieux, in a recent issue of Objektiv devoted to “The Flexible Image,” describes his motivation to “deconstruct the tools that create different kinds of abstractions” in a project that investigated the way police statistics create images. Prévieux: “These tools not only show the reality of crimes, they build it. The heat maps are gradient blobs based on isolated crime dots. They create continuous crime zones in between the dots, meaning that some areas without any crimes become potentially dangerous zones.”[2]

Julien Prévieux, Atelier de dessin – B.A.C. du 14e arrondissement de Paris. 2015. Courtesy of Galerie Philippe Jousse.

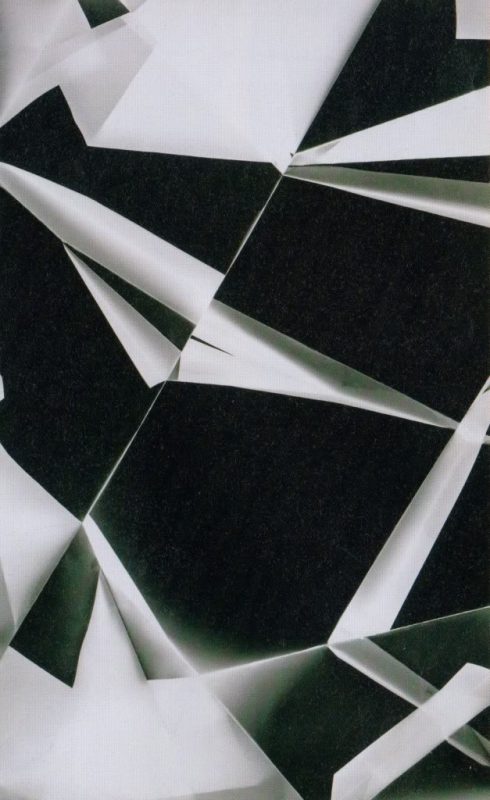

Formalwear

The “new formal photography” often takes on the materiality of the photograph, abandoning the question of information and truth entirely. What does the photograph need to be a photograph? We call many different things photographs now. A scanner can take a photograph. You don’t need a camera to take a photograph in this new world. A photograph doesn’t need to be “of” anything to be a photograph.

A photograph is a mark, a smear, a trace of its legerdemain. Photographers have always been manipulating images, but now as never before photography takes on the subject of its own manipulation. It is uniquely positioned to reveal and criticize its own rhetoric. It is the magician who is constantly showing her hand and asking us to ask of the bigger tricks in the world “how are they done?”

Eileen Quinlan, Untitled (mirror 054), cameraless scanner print, 2015. Courtesy of Eileen Quinlan & Cheyney Thompson Studios.

—

[1] Charlotte Cotton, Photography is Magic, (New York, Aperture Foundation, 2015), 1.

[2] Objektiv Issue 13, June 2016, p. 91