Another Land: After Noguchi | A Project by Leah Raintree

Noguchi Museum

9-01 33rd Rd Long Island City, NY 11106

August 10, 2016 – January 8, 2017

Monumental, geological, majestic—monolithic verging on celestial.

Leah Raintree—the artist behind Another Land: After Noguchi, a new photography exhibition now on view at the Noguchi Museum in Queens, New York—takes up these metaphorical dimensions (of Japanese-American artist Isamu Noguchi’s sculptures, that is), magnifies them, and makes them literal.

This process of literalizing the more poetic aspects of the late sculptor’s work, however, does not involve making his work any more physical or concrete, but rather the opposite.

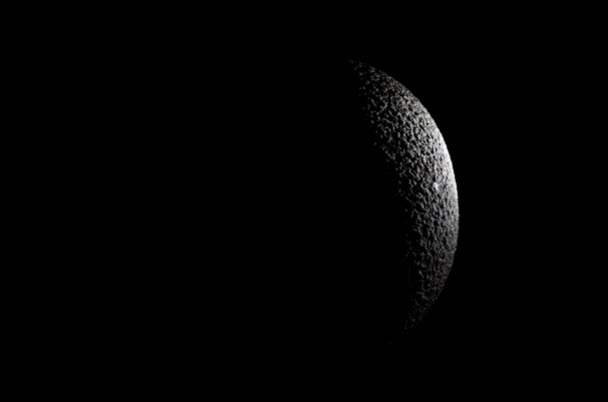

Leah Raintree, Another Land: Emanation, 2016. Photograph, 24 x 36 inches. Courtesy of Noguchi Museum

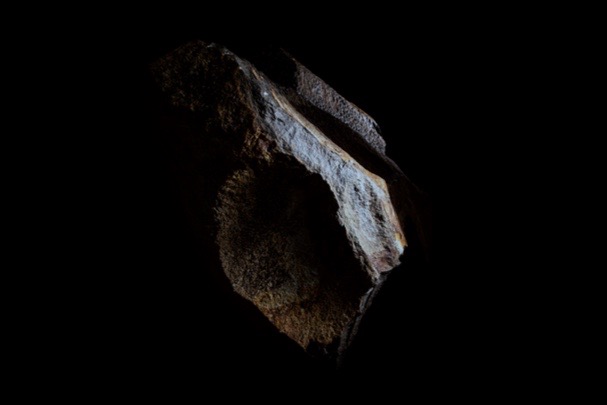

The exhibition is composed of 10 distinct pieces. Nine photographs, all of which grace the perimeter of the petite boxy gallery tucked away in northwest corner of the museum, reframe (or, as the press release states, “reimagine”) individual works by Noguchi as objects in deep space. These photos pontificate with a particular vernacular, using vast planes of velvety black and creeping luminous halos, to allude to not only to a general vocabulary of sci-fi fiction but also a lexicon of astronomical and scientific inquiry. (To shoot the photos themselves, Raintree used a technique called astrophotography, which, gaining traction in the late 19th century, facilitates the capturing and imaging of large distant bodies the celestial sphere.) Despite this focus on the two-dimensional, however, the central work in the exhibition is a single sculpture.

This sculpture—Another Land (Object for Hand), 2015—a palm-sized peach-colored stone, seated on a roughly four-and-a-quarter-foot-high pedestal in the center of the room, serves as a kind of axis mundi for the exhibition, becoming the hub, or gravitational center, around which Raintree’s photos, and by extension universe, revolve.

But, the funny thing is that the majority of these photos have little to do with this particular stone, as they are the imaging and reimagining of Noguchi’s—not Raintree’s—work. This insertion then becomes a kind of imposter, begging the question of: Why had Raintree not just used a stone carved by Noguchi?

Leah Raintree, Installation view of Another Land: After Noguchi, 2016. Courtesy of Noguchi Museum. Photo Credit: Nicholas Knight

Although there are a variety of hypothetical motivations that could be projected onto Raintree in answering this is question, I believe the stone is best understood as a kind of signature. An object fitted to the artist’s body—her “hand”—with which, upon looking, the viewer is reminded not only of her presence but also of her scale—her smallness in comparison to the immensity the photographs deceivingly propose.

The craggy surfaces of photographs leach their illusory mass, transporting Raintree, Noguchi, and the objects in question to a curious space between the terrestrial and the sublime.

It is precisely in this awkward space that the conceptual breadth of Raintree’s work comes into itself. The exhibition seems to synthesize questions of authorship (e.g. To whom should the work be attributed—Noguchi? Raintree? The terrain from which the stone was quarried? A lineage of astrophotography? All of the above? None of the above?) with general ontological inquiry (i.e. What is a human? What is the nature of the universe? What is the distinction between these two fungible bodies? And how does one understand oneself in space?).

Leah Raintree, Another Land: Give and Take, 2016. Photograph, 24 x 36 inches. Courtesy of Noguchi Museum

This conceptual project is further brought to light by the exhibition’s title, “Another Land: After Noguchi,” which holds a fourfold significance. First, the name alludes to Noguchi’s 1968 piece—Another Land—a roughly 10-inch-thick granite slab whose intersecting fractures create rectangular subdivisions in the stone that feel both apocalyptic and topographic. Next, the title references Raintree’s own Another Land (2015), a 10-foot-square astrophotographic imaging of a Noguchi, which the artist implanted horizontally in the soil at Socrates Sculpture Park (just steps away from the Noguchi Museum in Queens) when she was an Emerging Artists Fellow there last summer.

But beyond the indicated obfuscation of authorship that these references allow for—with different works derived of the selfsame material, possessing the same title—it is with the phrase “After Noguchi” that things really get complex. Firstly, in art historical convention the attribution “after” (see: “after Rembrandt” or “after Bruegel”) is used to indicate that a work in question either draws heavily on, or possibly replicates, that of another artist. In turn, “After Noguchi” becomes a sort of art historical pun that taps into the conceptual mechanisms at play, reinforcing the notion of a slippage in authorship. However, the phrase also possesses a direct reference to time; Raintree is making work after Noguchi. And, through manipulating Noguchi’s own pieces in this new temporal zone, the artist both embraces as well as questions time’s perpetual progression, proffering the possibility of elusion—of looking forward through looking back.

That being said, the utopic vision suggested by Raintree’s project—constructing a fourth dimension, a new connectivity, where material, image, formal discourse, and the subjectivities of Raintree and Noguchi all fold into each other—is thwarted by the knowledge that Raintree can never really enter the physical or psychological spaces Noguchi once occupied.

She’s on the outside, looking in.

She is an explorer who, by acknowledging her own limitations, simultaneously gestures towards her own paradoxical limitlessness.

Leah Raintree, Installation view of Another Land: After Noguchi, 2016. Courtesy of Noguchi Museum. Photo Credit: Nicholas Knight