To say “it made me cry” doesn’t mean much on its own—I’ve cried at an in-flight Kate Hudson movie, but that is because I cry at everything on an airplane. Though, I remember unexpectedly and authentically crying when Rachel dies in Thomas Mann’s biblical TALES OF JACOB. Works of art give us death as an abstraction, an emotional rehearsal that falls away when facing the concrete reality of losing a loved one. Between those poles—abstract and concrete—there is a strange intermediary: the death of people you have certain feelings about, but no lived relationship with—artists, actors, cultural figures. It’s hard to know how to deal with this: I’m uncomfortable with the performances of public mourning for celebrities across social media, which can’t help but feel like kitschy insincerity.

What I’m trying to say is that Rene Ricard’s death deeply upsets me, and I’m not sure what to properly say about it, but I picked back up my copy of his first book of poems and it made me cry.

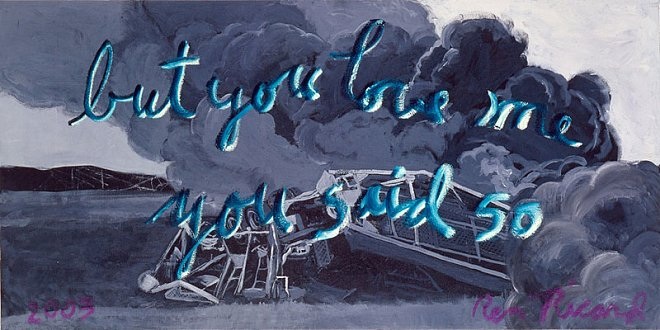

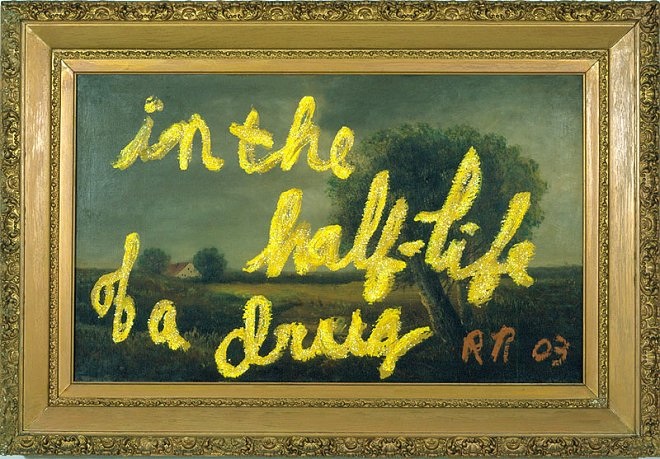

His paintings, poems and criticism are among my greatest inspirations. They are brilliant like diamonds, dazzling with color but utterly precise. They tell you they are about flashy trickery while being the real deal—unapologetically violent and overwhelmingly fun. (One of my dreams is to collect his disparate art writing for publication—exactly the infusion the art world needs right now.) Wicked and nasty and fantastic and free—as a way being in the world, they gather experiences as extravagant riches.

Two moments thinking about RR:

1.

Laying in the Brooklyn afternoon

with a handsome stranger

I said I would write him a poem:

FOR GEORGE’S ASS.

Sitting in the sun of the Luxembourg

gardens I realize I never did.

2.

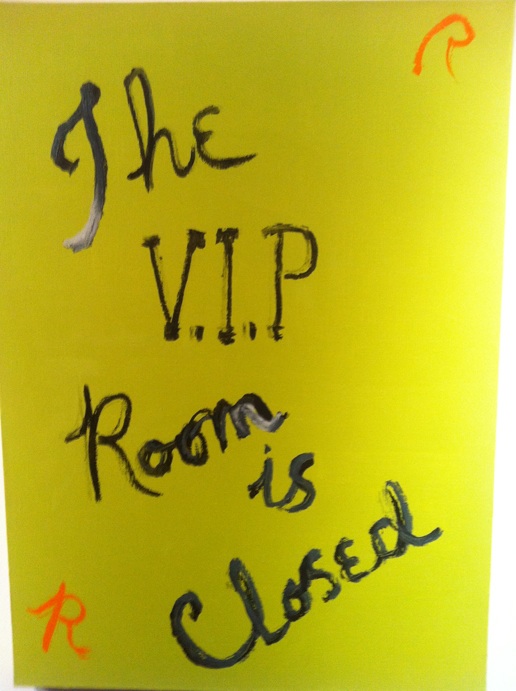

A friend was working as the sole attendant

of a store on Great Jones st.—

there were four Rene Ricard paintings there:

grey and acid green.

My friend locked the glass door and put up a sign;

just like in The Big Sleep.

I sucked his cock beneath the paintings,

like a halo, like a sign.

I tried to meet Ricard, to interview him, through the intercession of beloved mutual friends, which he flatly refused. Somehow I always liked that too, it dripped with reckless romance—I took it as an invitation for prolonged seduction, certain that one day it’d be worked out. Which is, in a stupid but immediate way, why his death was so shocking to me—”but we aren’t friends yet!” Then the real sadness of realizing the loss of him as a force—how much more exciting it was to know that at any given moment he was somewhere mincing about, terrorizing and charming.