Matthew Schreiber: “Sideshow”

Johannes Vogt Gallery

526 W 26th Street, Suite 205, New York, NY 10001

April 10—May 10, 2014

Matthew Schreiber, “GateKeeper” (2014). Laser diode modules. Courtesy of the artist and Johannes Vogt Gallery, New York.

“Architecture is the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light.”

-Le Corbusier, “Vers une Architecture” [“Towards a New Architecture”] (1923)

Light and shadow, as a form of structural aesthetics, is hardly a novel phenomenon. And yet, artists and architects consistently search for outlets where practical physics may be teased at or changed, entirely. In his solo exhibition Sideshow, at Johannes Vogt in Chelsea, Matthew Schreiber utilizes varying stages of light as the conceptual anchor for experimentations with holograms, lasers, and the disorienting experience of a total blackout in a darkroom capsule (called a tumbler) previously owned by Life Magazine photographer Art Shay. While the show’s title might have immediate associations with circus freaks and events considered too “strange” or “alternative” for a general audience, Schreiber’s elegant setup is the antithesis of the greasy, imaginary barker shouting “step right up!” Having served as a chief lighting expert for James Turrell for the last thirteen years, Schreiber’s work for the artist paid great dividends, leading to the nationwide retrospective between LACMA, The Guggenheim, and the Museum of Fine Arts (Houston).

Matthew Schreiber, “Dark Tumbler” (2014). Courtesy of the artist and Johannes Vogt Gallery, New York.

Somehow, though, Schreiber’s collected works feel more intimate to an observer than the “shock-and-awe” of a Turrell installation. Granted, he doesn’t shy away from a chance to take one’s breath away: with “GateKeeper” (2014), an intricate weave of red laser lights in an enclosed room, fine threads of light crisscross the ceiling effectively producing a virtual, woven roof. A potent exploration of the absence of light is explored in “Dark Tumbler.” Its practical use is to seal out external light sources from a traditional darkroom environment, allowing for an unfettered development process when entering and exiting the area. For Schreiber, it acts as a kind of “sensory deprivation chamber,” a portal from the illuminated world into the void. It is a telling metaphor for the fetishism surrounding the opposing poles of light and dark: any venture into a complicated or poorly defined “grey area” is considered unhealthy or unwanted (ironically, this is where most of the world’s artists spend their intellectual lives).

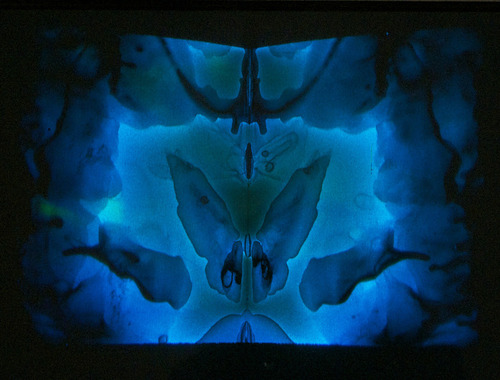

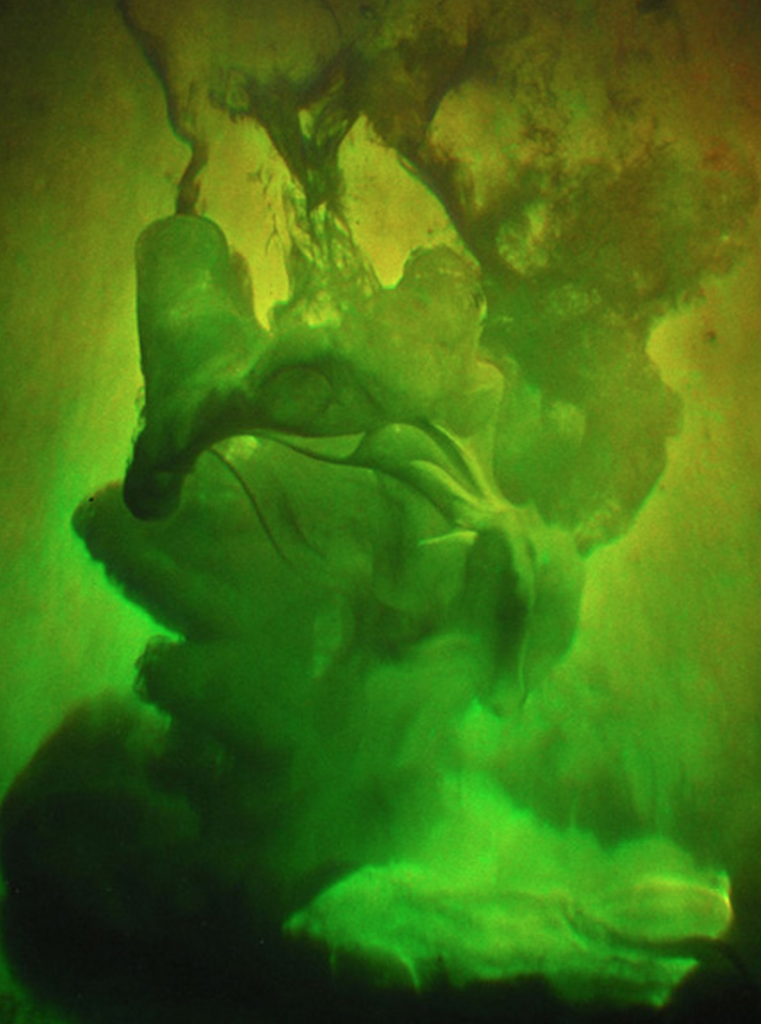

Matthew Schreiber, “Holographic Klecksogram 1″ (2012). Hologram, 6.5″ x 8”. Courtesy of the artist and Johannes Vogt Gallery, New York.

Speaking of such, a particularly tantalizing work is “Infrared Pentagram.” The light sculpture is situated near the front of the gallery, where baffled guests kept asking, “what am I supposed to be looking at?” It is, as Schreiber says, a “perfect” pentagram, only visible with night-vision goggles: a controversial, if not eyebrow-raising, choice of a symbol. Schreiber keenly identifies a form of signage that requires a kind of extra-sensory effort to see its geometrically and mathematically true state. Holography, too, also requires locomotion in order to observe its respective formations. Contemporary culture has seen holograms crossing into everything from gumball machine novelties to the creation of virtual targets for military training exercises. Schreiber’s holographic works, reminiscent of Rorschach’s inkblots, are further evidence to the breadth of the “see what you choose to see” mantra of the exhibition.

Niépce, Daguerre, Fox Talbot, and Herschel captured light for the first time. Muybridge showed the world that light in motion could be art. Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy taught the world to see light as art. Flavin democratized light as an art form, and an architectural impetus, by creating situations of beautiful ubiquity. Julian LaVerdiere and Paul Myoda created “Tribute In Light” (2011) as a visible but intangible memorial to a murdered structure, its occupants, and those who sacrificed themselves in its wake. Artists such as Elíasson, Turrell, and Emin have all bent and shaped light into mediations of the world, the self, and art. This list may be an incomplete history of individuals who have worked with light as part of their respective practices, but it serves to illuminate how artists like Schreiber can still captivate an audience with an original incarnation of that which informs our most basic (and for art observers, most essential) sense: sight.

For more information about the exhibition, visit Johannes Vogt Gallery.