You were the founder of the Los Angeles-based performance/music group OJO. Can you talk about its origins, the collaborators, and how this fits within a larger context of your artistic practice?

OJO was created when I was at UCLA in the mid-2000s. There was a dingy little sound room we named the Clam, where fellow students would go and record strange music. It was a sensory deprivation-tank-like space. I met Joshua Aster, Justin Cole and later Brenna Youngblood and two other non-UCLA people Chris Avitabile and Moi Medina in the Clam. There was no specific intention to our group other than to create sound in a free way, with no designs on being a band but also not really declaring ourselves an art performance group. Our first performances centered around really loud beats I created on my 808 drum machine, which I had recently found at St. Vincent De Paul. We loved that strange minimal boom of the bass and the different pitches it was capable of and we would create these strange environments with a bunch of slide projections, video projections, and a huge stack of speakers in the middle of the room, also sometimes pouring hundreds of pounds of salt on the floor to add to the sound of shifting sand under your feet. It was really magical but also totally lo-fi and low budget and we all loved the freedom we felt in exploring sound while simultaneously exploring ideas of performance. There was no specific composition, just really open movements that we all were aware of, and once a performance started we had no idea where it would take us, because we also gave the audience the power to influence the sound by including them in certain actions. Musically we were all influenced by sparse acoustic guitar players like Sandy Bull or John Fahey but also totally into Tangerine Dream, Popul Vuh, all the way to Kompakt Records from Germany and J Dilla, so we were pulling from a ton of influences when it came to music. It was a part of all our lives for probably around seven years until our dream was fulfilled when we performed in Bilbao, Spain in 2012, and since then we’ve all gone on our own paths. I still really miss playing with OJO and really love and miss everyone involved but I also know that’s how everything goes and I’m happy that we even had what we had. I don’t know how it fits into my larger practice because to me there is no hierarchy in my work, I have always addressed needs in my life as they come and that’s how art has always been to me.

What is the connection between your musical endeavors as DJ Lengua to the relating of cultural archiving, memory, and re-imagining of history through the language of music?

My Lengua production work was a way to connect to people without asking for permission from those that hold the keys to the white cube. Lengua means tongue in Spanish. Lengua allows us to communicate. Lengua also makes great tacos. I started producing back in ‘99 and have since the beginning pulled from dance music from all over the Americas, the first LP I did was with you! It had hi-energy as well as dancehall, mambo and cumbia influences. Growing up like a typical American kid I was into hip hop and skate culture, but there was always another side that I was exposed to when going to see family in Peru that would expose me to a very different, native South American vibe. All of this gave me a unique way of seeing the Americas and pop culture and folk culture; I see my music as a way of illustrating that, and feeling it. I also was exposed to the Sonidero music scene in D.F. back in the ’90s, and through that I learned so much about the bigger picture of Latin America and it’s music. I also felt the need to collect and piece together these lineages because they were getting ignored and were getting lost in the rush to modernize Latin America, so my friends and I started a successful night club called Club Unicornio and also I helped my friend Sonido Franko start his blog Super Sonido (http://supersonido.net/) where we post free MP3s along with info about the music we love. Lengua is/was a way for me to tap into popular forms like straight up dance music or cumbia and play with tracing an alternative map of the Global South, the same way so many of my favorite DJs and producers—TOTAL FREEDOM, Fatima al Qadiri, Nguzunguzu—are working today.

In your early work from the ‘90s and early 2000s, your “new folk” paintings explored your personal experience growing up in Tucson, Arizona. Can you describe the unique cultural landscape you grew up with and the influences that it had on your work?

Eungie Joo wrote a piece in Flash Art back in 2002 in which she included me, describing my work as a new form of folk; in a way I guess it was a precursor to the whole freaky folk musical scene to come out of the Bay Area. I used to resent the word folk. I felt like it was a way to say my work was simple, old fashioned, or had some tie to traditional values, but now I’m cool with it, I see it as going against the dominant flow. Regarding my upbringing, I’m from two very different cultures, one based in the U.S., you could say redneck, a very western culture—my cousins in Arizona round up cattle near Bisbee and Agua Prieta. I’ve never been a country boy but totally get it, I love the desert and dirt roads—not the politics, but love the people. My other side is from the mountains of Peru. So I always got this really intense blend of influences and memories. When I was a kid we would go to festivals in the mountains of Junin and Huancavelica to be specific. These festivals were for me completely surreal, Fiesta Santiago, for example, is a celebration of the animals by the campesinos of the Andes. They drink and dance for a month straight, day and night, with incredible music. It’s a celebration with roots go way back before the Spanish arrived in that part of the world. There are strange characters that populate that world, they give blessings to the animals for good health, just like in the ancient pagan world but now it’s totally mixed up with pop culture references and cartoon characters and Catholicism. I have always been drawn to these dances and also to the Yaqui dances from Tucson and Sonora. To me I could see the connections, I could see the through line that connects these very different places and so I set out to illustrate that.

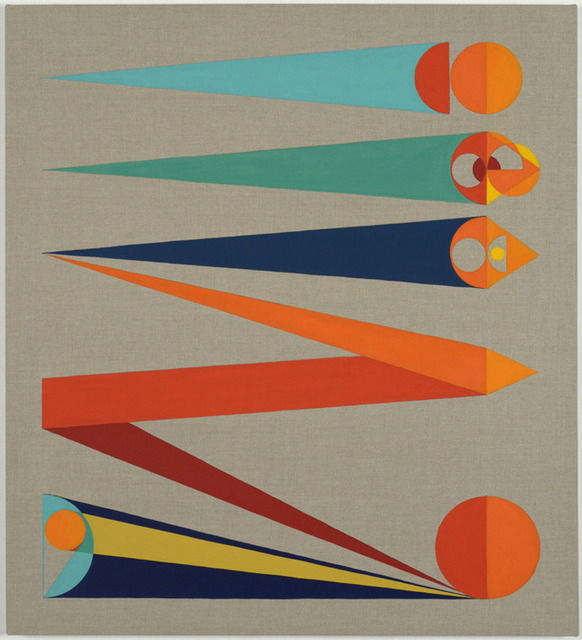

Shifting Right, 2014. Flashe on linen. 42 x 38 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

How is your new body of work a reflection on this past tradition and new interests?

It’s not a conscious thing, I have moved away from being autobiographical. Lately I just want to make work that speaks to a certain simplicity—simplicity in color and form and in process as well. Whether I’m sitting down concentrating on making a small painting or doing a video work, I’m looking for a way to convey complexity in basic forms. I do reflect on larger historical manifestos such as Oswald de Andrade’s Cannibal Manifesto. It’s amazing how something written in the 1920’s can still be so relevant. It speaks to the idea that cannibalizing other cultures is our greatest strength as people of the Americas. We are all people that have our feet in two worlds especially now as the Internet is creating such a strange mix of everything.

Is there a connection between your geometric abstraction paintings and what is referred to in music as open tuning techniques? Are you riffing off the actual musical methodology or more about “open mind tuning” and how humans used it to alter their consciousness?

I definitely like the idea of what open tuning represents. To me it represents the fact that we are shaped by our landscape. It’s also about simplicity. You can give someone who doesn’t know how to play the guitar an open tuned guitar and it will sound good. It also connotes location, like the Mississippi Delta has its own specific open tuning just as Hawaiian music has its own. The connection probably resides in the specific parameters that I have regarding shapes and colors, and there is a template of sorts, just like in open tuned music—there is a set template of sounds you choose from to create your individual sound. I came to abstraction after working a long time in figurative work so for me it’s really like thinking of the world in a totally new way. Abstraction is such an instinctual way of seeing and feeling; it’s the root of our perception. Over the past ten years I’ve been slowly losing eyesight in my right eye, and I’ve noticed the affect on my work. I’m forced to flatten everything out and to allude to space with flat color. I’m being forced to create a lot more with a lot less, so I think that’s also another way the two relate.

In a recent review for your 2013 exhibition, Smuggling The Sun by New York Times art writer Ken Johnson, he ends the review by posing the question “What would his paintings be like, I wonder, if he put his all into them?” referring to your desire to not devote your practice only to painting and his desire that you only create paintings. How does this type of questioning lead you to consider audience more in the production or understanding of your work?

That was a really great review because to be asked that in such a public format is pretty intense. It definitely made me question the idea of singular aesthetics, and it also made me ask myself, what is this drive to create in so many mediums? My friend and I were just talking about Kai Althoff and he described him as a style jumper; I guess in a lot of ways that’s how I feel the arc of my work has been as well. The question of audience is totally relevant, because as a music producer I could get my work and ideas out to so many more people through very populist means on the Internet like SoundCloud and earlier, MySpace. My cousins and friends in Mexico and Peru could download my music and be totally involved in my practice. I even have fans in far-off places like Odessa, Ukraine, and Frankfurt, Germany. There are amazing vocal remixes of my beats in Argentina and Holland. I guess the way I saw painting and sculpture was that it was very much a rarefied object and comparatively the art audience is very small and very specific, and to get access to the spaces to get my artwork out into the world can be very frustrating—there’s so much BS in the gallery world. But I don’t like to dwell on the negative aspects of the system, instead I like to keep focusing on the work and I have found that if I look at production as a way of life then it will be something that never stops. Those thoughts have driven me to be much more single minded in my approach, and ever since that show I have been much more focused on my painting practice, although my two upcoming exhibitions involve major video pieces, one that was filmed in the Amazon with you, and the other in the highest mining town in the world. I’ll never completely abandon other formats, but there isn’t a day that goes by that I’m not holding a brush in my hand; it’s something deeply rooted in my life. Currently I’m waiting for the proper opportunity to exhibit a new body of works that I’m really excited about; maybe I’ll get another opportunity to hear what Ken Johnson has to say about them.

The Peruvian guerrilla group Sendero Luminoso (The Shining Path) adopted a Maoist ideology in the early 1980s. What were some of the repercussions to Peruvian contemporary culture and to your own family? Is there any connection to this within your artwork for the Road to Ruins exhibition in 2010?

That period shaped the experiences I had visiting Peru as a kid. It was a terrible time, my family suffered like so many other people that were caught in the crossfire between the guerillas and the government. The poverty was also a form of violence and it was always very hard to see my family in such dire circumstances and yet I was able to leave and be here. Regarding the Shining Path and the effects it had on Peruvian contemporary culture, we could write a huge book on that subject alone, but in a nutshell, it forced a mass-migration of campesinos—country people whose customs are indigenous and language is not Spanish—into the capital city of Lima. That had a very powerful impact on the physical infrastructure, or lack thereof, of Lima and it also had a profound impact on the historically racist attitudes people from Lima had towards the campesinos, also referred to as “cholos.” The word “cholo” is really interesting because it’s a lot like the word “nigga” here. Back in the day it was a way of putting someone down, an insult, but over time it became a term of endearment. Its meaning changed as so many cholos were migrating into the city and their culture transformed the urban cultural landscape. Peru is hardly over its fucked up racism but things have gotten better in a lot of ways. The connection I was making in Road to Ruins was that I had an album by the ’80s Peruvian chicha band Los Shapis and the album artwork was an appropriation of the Ramones album Road to Ruin. I fell in love with this ripped off cover art. It symbolized so much to me; I related to the dual identity it reflected within my own life and it also was such a great use of piracy out of necessity, it was really “punk” without even being punk music. The title of the Ramones album also made me reflect on how ruins are all that anyone knows of Peru. Every time someone finds out that I’m Peruvian they ask me if I’ve been to Machu Picchu or some shit like that. It took me over thirty years to ever get to Machu Picchu! But more than anything I like to think there was some subconscious connection, a sublime collision of underdogs—Los Shapis, a bunch of cholos from the Andes with The Ramones, a bunch of degenerates from Queens, NY.

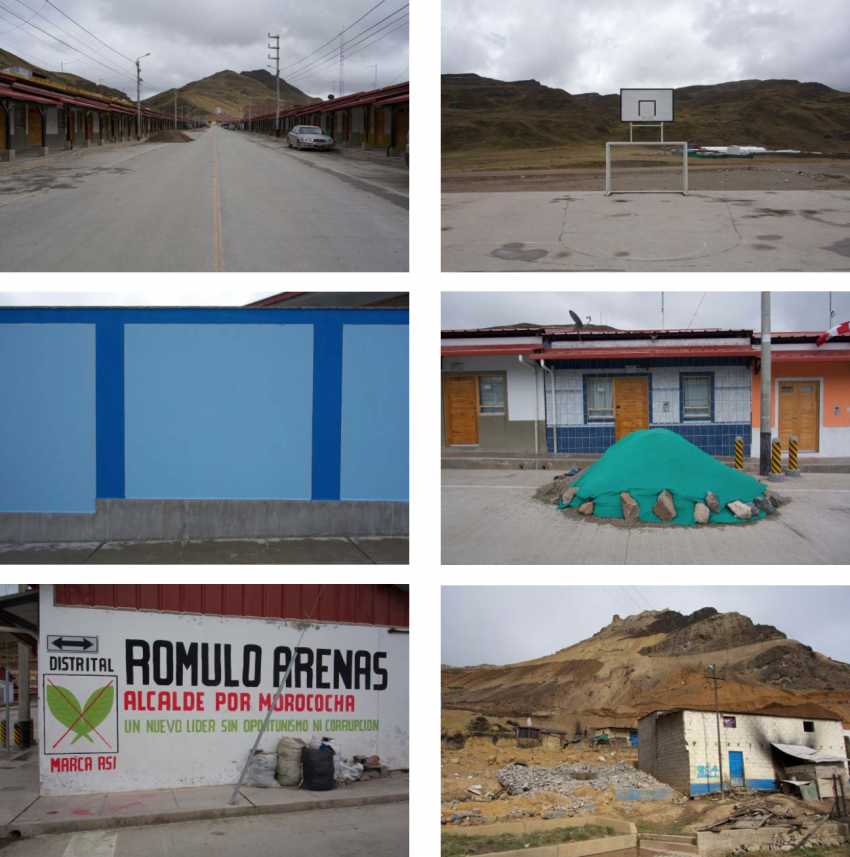

Morococha, 2014. Production Stills. Courtesy of the artist.

The history of Asian labor and culture in Latin America is relatively unknown in the Western world. Through your own artistic inquiry can you speak about your research on the subject matter and current events that drive your Morococha project that you are creating for LAXART in 2015?

Even within Latin America there’s a certain amnesia regarding Asian immigration and indentured labor from China and Japan. I was interested in how the relationship between Peru and China in the recent past was through Maoist ideology, the Little Red Book and the Shining Path, and how that relationship has turned into the opposite scenario in which Chinese government-owned companies are buying up Peru’s natural resources to keep up with the global demand for their products. It’s such a radical flip in terms of ideas of progress and social aspirations in both countries. A little over a year ago I had heard about plans that a Chinese-owned mining company named Chinalco, was relocating the whole population of the town of Morococha, the highest copper mining operation in the world. Morococha was also a town that I had passed through on my way to visit family my whole life, and such a harsh and inhospitable little place, so it was surprising to read the name Morococha in the New York Times. I was fascinated with this new relationship to Asia and also how Chinalco was approaching relocation of the population. Chinalco had constructed a brand new town about 10 miles away from the old town. I became really into the idea of documenting the old town in the process of becoming a ghost town, not quite dead yet but in the process, like the faint vision of a phantom hovering over a real body. I was also interested in seeing the architecture and planning of the new town, a “just add water” pop-up town. So I went up to Morococha this past August to see what I could find. I was warned by the company officials I met with that the town had been placed under a state of emergency, and that they are not responsible if anything were to happen to me. When I arrived there, which was a very grueling and dangerous drive through the mountains, there were still some buildings standing inhabited by people that hadn’t agreed to the terms of removal and were very suspicious of anyone, much less me with a camera entering this apocalyptic landscape they called home. The video is called Morococha and will be showing at LAX-ART this coming January 2015.

Open Tuning (E-D-G-B-D-G), 2012. Hydrocal, cocaine, steel, copper, twine, flashe. 74 x 27 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Living for the past 11 years in Los Angeles, you must have seen the art market and art culture shift and fluctuate to its current state. The new “Warehouse Era” gallery boom in the downtown area with such spaces as Night Gallery, the Mistake Room, Gavin Brown’s enterprise and François Ghebaly among others. Do you think this is bringing L.A. a new art platform? Are there any other movements happening that we should be aware of?

Yes, I have seen a lot of changes in the art scene of L.A. I’ve also seen a lot of changes in the demographics of this town too. My neighbors used to have shaved heads and wear Nike Cortez with white socks pulled up and run through my backyard running from the cops. Belmont yards were still totally active. Now, instead there’s a huge condo on top of the yards and my neighbors have beards and drive Volvos. I can’t say that I loved having my thug neighbors point lasers at me at night but I also don’t like seeing poor people constantly pushed out. It’s hardly something that’s unique to L.A. Specifically talking about the art scene, I’ve seen an aversion to content in L.A. Everything seems to be funneling into strictly formalist concerns and pseudo-transgressive work. L.A is definitely pushing hard to be regarded as the new capital of contemporary art but in reality it’s still very small and local. I’m glad Cesar is bringing in artists from outside. I especially like Korakrit’s strange brand of mind-bending. I really like Francois’s program and he has a loyalty to his artists that is really admirable. I don’t know much about Night Gallery and Gavin Brown’s Mission space other than it seems like a lot of cool people hang around there. I do think the addition of Hauser & Wirth and Schimmel downtown is definitely a game changer in regards to the blue chippers. I remember Chinatown gallerists bemoaning the fact that collectors would never drive east of La Brea and now it’s exploding downtown, with gallery shrapnel hitting Boyle Heights. By far the best gallery in town is The Box run by Mara McCarthy—it’s downtown. As far as artists whose work I’m into: Cayetano Ferrer, Gala Porras-Kim, Gina Osterloh, Math Bass, Erik Frydenborg, among many others. I remember George Kuchar telling me the only good art movements are bowel movements. He also said that while he was filming he knew it was a good shot when he drooled. I found myself drooling a lot in the Amazon.