[This interview also appears in Spanish in DFAQ.]

What do you see as being the most contemporary and relevant themes as you work with these artists who are spread across Central and South America?

First of all, we are not only working with artists from Latin America. We do acknowledge the fact that the fair is taking place in a specific geographical (and socio-political) context, but we are trying to expand the “sur” section beyond the limits of Latin America. I guess the main reason for that is that neither of us is from Latin America. We do relate strongly to the concept of south, both as a metaphor and as an ethical imperative, since we are both from Portugal, a southern European country struggling tremendously with a severe economic crisis and with the new north-south divide that is currently splitting Europe in half.

For this specific edition of Sur, and given both our backgrounds and our fields of research, we are more interested in developing a speculative curatorial approach than working with specific themes. More specifically, we are interested in the way in which one produces the future through imagination, but also through knowledge and action. And in a way, that is what we are trying to address with our case study #1. We are currently in the process of deploying a curatorial device of sorts that will enable us, but also the artists, the collectors, and the audience to think about what future we are able to imagine and produce at this specific moment in time. The project includes solo presentations and also a performative panel in which we will engage directly with producing what is yet to come.

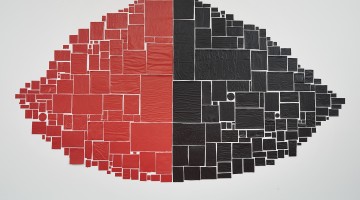

Cinthia Marcelle, The Tempest, 2014. Photograpy (diptych). Courtesy of Zona Maco.

How do you imagine the context of Mexico City, and especially of Zona Maco, changing how people will come to view the artists taking part in your incarnation of Zona Maco Sur?

The Mexico City we imagine (imagination being a keyword of our project) is an extremely cosmopolitan city, with a long tradition of engagement with the arts. It isn’t any different from New York, São Paulo, or L.A. In that sense we don’t expect the perception people will have of our project and the artists we’ve invited to be that different from that which people from those cities would have.

The artists involved with Zona Maco Sur are supposedly part of “solo show projects.” How important is the idea of artistic autonomy in the face of curating a group of individuals that have been designated “sur,” presumably based on the countries they are from?

As we mentioned before, and for this edition, Sur is less connected to a specific geographical situation or a specific theme than to a speculative condition we wish to inhabit.

What we understand as “the south,” coming from Portugal, is probably very different from what “the south” means to you or what it means in the context of Zona Maco Sur. Can the south be a place of speculative imagination? Can we recover it as a tool for producing the world in which we want to live? We don’t know and that’s why we call this a case study. The artists we invited aren’t representing any geography or nation. They represent nothing other than their own subjective view of the world, and this is an extremely important condition from which we always depart and in which our projects are grounded. This specific view of the world, which they are contributing to the project, is a complex and speculative one and is the reason we invited them to be part of Sur.

Petrit Halilaj, I Don’t Have a Room, I Don’t Have a Mind, Nevermind!, 2014. Mixed media. Installation view at Chert, Berlin. Courtesy of Zona Maco.

What are, if any, the principles or algorithms that you have set as a marker for which galleries and/or projects get included?

Again, imagination is a keyword, but another keyword is speculation. While imagination can be seen as a curatorial keyword for this project, speculation can be understood as an artistic keyword. All of the artists we selected are committed to a certain degree to speculation as an important modus operandi. Even though the end result of our proposal may look disjointed at first, we are looking for a digressive approach, branching out in a million different ways, each of which can be a new possibility, rather than simply focusing on one single narrative, or theme, or voice that would narrow down our possibilities of imagining the future.

Has Zona Maco brought attention to issues that South American artists want to express via the conduit of the exploding Mexico City art scene?

We would definitely say yes.

Finally, how do you think Zona Maco has or has not “defined” what is considered Latin American art?

We tend to be somewhat suspicious of national or geographical definitions of contemporary artistic practices. Nevertheless, if one looks at the role Zona Maco has had over the years, it is obvious that it has been of paramount importance in defining a place of high visibility for artistic practices that come from or refer to Latin America. But it hasn’t been a solitary endeavor; we think it has been the articulated activity of artists, curators, critics, galleries, collectors, and museums over the years that has resulted in the position it occupies today.

Zona Maco 2015 takes place February 4–8 in Mexico City.

This interview first appeared in DFAQ, issue 1.