Alice Shaw: Golden State

July 17 – September 4, 2015

Gallery 16

501 3rd St, San Francisco, CA 94107

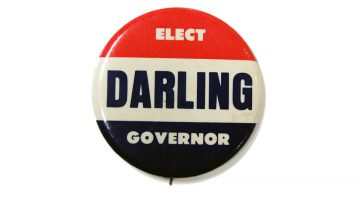

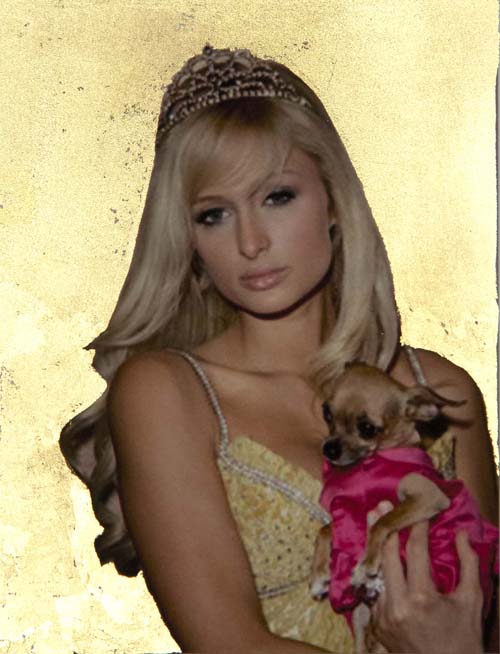

Alice Shaw’s solo exhibition, Golden State at Gallery 16, takes its title from the nickname of California. Throughout the exhibition, there are references to the Bay Area in particular, featuring iconography such as the Golden Gate Bridge, but there are also references to Los Angeles and its fixation with fame. Further narratives include California’s car culture, religious diversity, shopping, and body image, but one glaring observation is the overarching theme of money and commodification. Several pieces in the exhibition are accented with gold leaf, which lend a regal quality to otherwise banal objects such as tourist postcards or pop culture imagery, such as Paris Hilton. Likewise, concepts of worship and worth are called into question. During the opening reception, when asked about the use of gold in her work, Shaw stated that she is commenting on increasing the value of the work by applying gold to it.

Alice Shaw. “Entitled #1 (Paris Hilton),” 2015.

Archival pigment print,

4″ x 3″

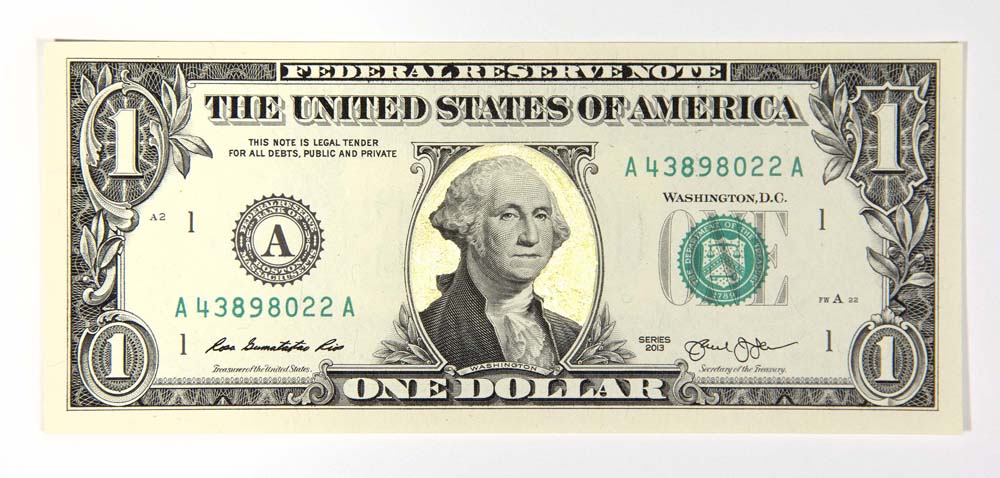

I would argue that the gesture also places the work within the context of monetary exchange. If an artwork has a subjective value, applying gold to it renders it a competitive object for trade on the market. In 2005, gold was worth on average $400 an ounce since the late 1970s, and prior to that it trailed at $35 an ounce since the late 1700s. Currently, the price of gold is slightly over $1,095 an ounce. Last fall, it reached $1,313, and in the summer of 2011 it spiked to $1,901, an all-time high. After spending some time on business journals, I learned that the value of gold is in direct correlation with the value of the US dollar. When elusive and speculative value decreases, people look to tangible goods such as gold or real estate to invest in, and therefore the demand increases for these goods. Basically, since the economic crash of 2008, gold has increased steadily in value. The dollar has slightly propelled itself back up again, but it is still worth only half of what it was in 2001, whereas gold has only steadily increased overall, now exceeding what the dollar was worth in 2001. Subsequently, as the value of the dollar increases, the price and ultimately the value of gold should go down (as will real estate). Art however, does not operate with this kind of exchange, but in general its value increases over time, and is oftentimes subject to trends in taste or publicity.

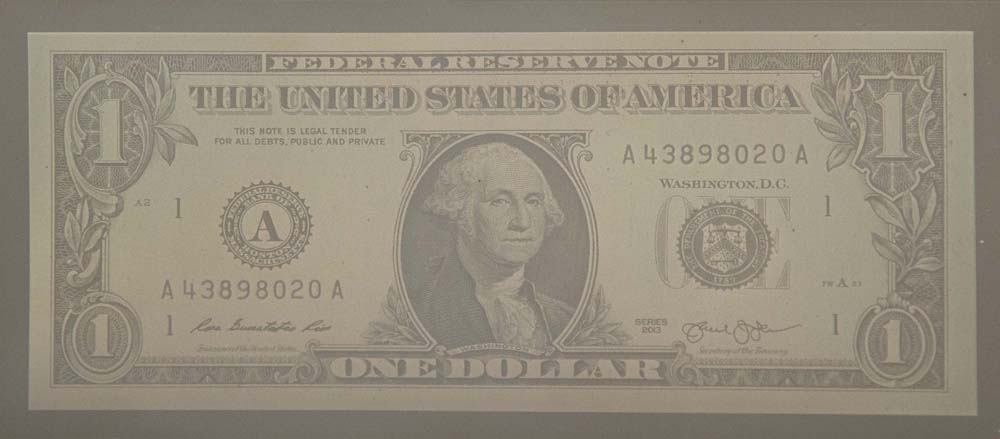

Alice Shaw. “Inflation,” 2014. Paper, engraving, and 22k gold leaf,

3.5″ x 6.25″

This brings up several arguable notions about the “art market” and the value of art beyond its role as a mere communicator of commodity. By communicator I mean that artists often use the economy as a subject for critical commentary in their work. The sad irony, as many of us know, is that art prices are often inflated by other notions of fame or popularity that are tied with the reputation of the artist. Unlike gold, an inert thing, people yield contentious and constantly fluctuating value that is subjective and wholly dependent on many other factors besides raw goods. So, the real argument with pricing art is not with the objects themselves, but with the value of the people who made the object or with the reputations of those who represent or exhibit the artists’ work. Not to open an entirely different can of worms of how gold is acquired and the value of people who mine it, let us return to Shaw’s exhibition and how her work is contending with arguments surrounding the potent value of subject, imagery and material.

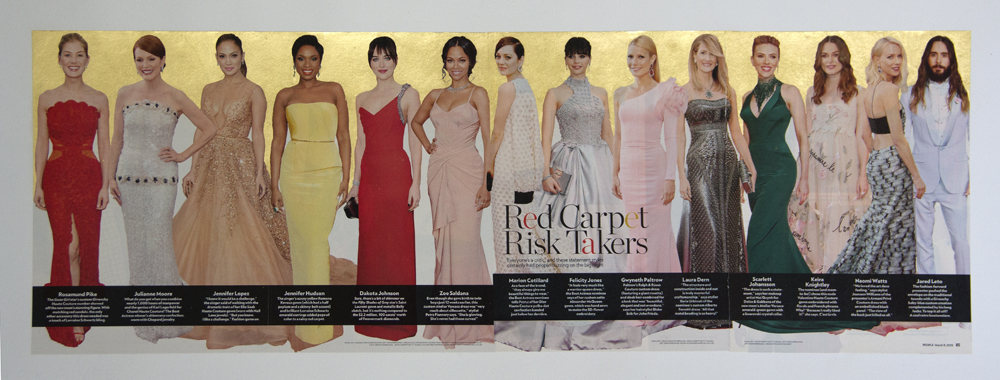

Alice Shaw. “Jesus and His Disciples,” 2015.

Offset print and 22k gold leaf, 10.5″ x 32″

Jesus and His Disciples is an off-set print featuring a re-appropriated image from a pop culture magazine of red carpet starlets in their gowns, such as Jennifer Hudson, Scarlet Johansson, Keira Knightley, who are accompanied by Jared Leto (sporting a beard and long hair). The headline of the magazine reads “Red Carpet Risk Takers.” The text claims that, by wearing a daring outfit in public, one is taking a risk. The confusion here is that the risk is a materialistic one: a risk of ruining one’s livelihood or living without actually risking one’s life. The background behind everyone is embellished with 22K gold leaf, hand-applied by Shaw. The gold renders the subjects as icons—most akin to an illuminated manuscript—but the double entendre of icon is also situated in American culture’s fixation with celebrity worship. The worship of the almighty dollar is also suggested in the piece Inflation: a dollar bill with a 22k gold leaf halo surrounding George Washington’s head.

Alice Shaw. “Silver Dollar,” 2015. Digital Daguerreotype, 3.5″ x 6.25″

In addition to gold, Shaw also incorporates silver in some of the works, which brings up another conversation about the value of precious metals and their trade worth. For example, the counterpart to Inflation is the piece Silver Dollar, which is a daguerreotype of a one dollar bill. Ironically, this piece may be more valuable than the other simply because of the rarity of its material as a photographic process that is on its way to possible extinction. However, unlike gold’s current value at over $1000 per ounce, as mentioned earlier, silver is only valued at around $14.50. This comparison is particularly apparent in two small embellished postcard images that appear to be from the late 1950s. Golden Gate features an image of the Golden Gate Bridge with the sky above covered in 22k gold. In contrast, the Bay Bridge piece titled Silver Gate features the sky covered in silver leaf over the still existing western portion of the bridge spanning from Treasure Island to San Francisco; the silver usage implies that the East Bay is the lesser valued location. Incidentally, the eastern half of the bridge is being deconstructed at this very moment, fading into extinction like the daguerreotype, although much faster.

Alice Shaw. “Key To The City – San Francisco,” 2014. Brass, 1″ x 2.5″

Shaw is predominantly a photographer, and the use of appropriated imagery in her work is further commentary of the value of the images. Photographs convey meaning with the subjects they represent, which is where the true value lies, not in the cost of the paper to print to image upon or the amount of time it takes to snap a photo. Yet, through embellishing her work, Shaw renders the photos as hand-made objects, thereby challenging their singularity as a two-dimensional documentation, and recognizing photography as something more. This tactile quality extends to several three-dimensional pieces in the show as well, from altered credit cards to a one dollar bill, folded into the Coit Tower, and a real key carved with the San Francisco skyline.

Alice Shaw. “Comforter,” 2014/15.

Satin, polyester, and thread, 89.5′” x 54″

The standout, however, is the satin metallic silver hand sewn quilt titled Comforter. The quilt features the ominous, unfinished pyramid and all-seeing Eye of Providence motif of the Great Seal of the United States, found on the back of the one dollar bill. Sitting and sewing a quilt is the antithesis of the act of taking a snapshot. This slow process is more analogous to old chemical photo processing techniques, which required hours of patience before seeing the results. Unlike digital photography, hand developing photos is also becoming extinct like the daguerreotype, and the Bay Bridge—and the act of sewing could also become a fading art. Certainly, many hand-made things have gone the way of mass production. Yet, instant replication has been one of photography’s benefits since its invention and onset in the general market in the late 1800s, which brings up issues of originality. Comforter, on the contrary, evades the problem of originality that photography began to create for the art world. Additionally, its subject matter seems to epitomize everything that is wrong with the world: that almighty (questionably so) dollar. The quilt, along with the rest of the exhibition is deeply seated in rich and multiple interpretations of commodification, iconography, debt, wealth, nostalgia and so much more. Shaw puts these conversations of worth before us, reminding us that art has more to say than a dollar, which is a very potent comfort.