Atsushi Kaga: I am here with you

July 2 – 31, 2015

Jack Hanley Gallery

327 Broome St. New York, NY 10002

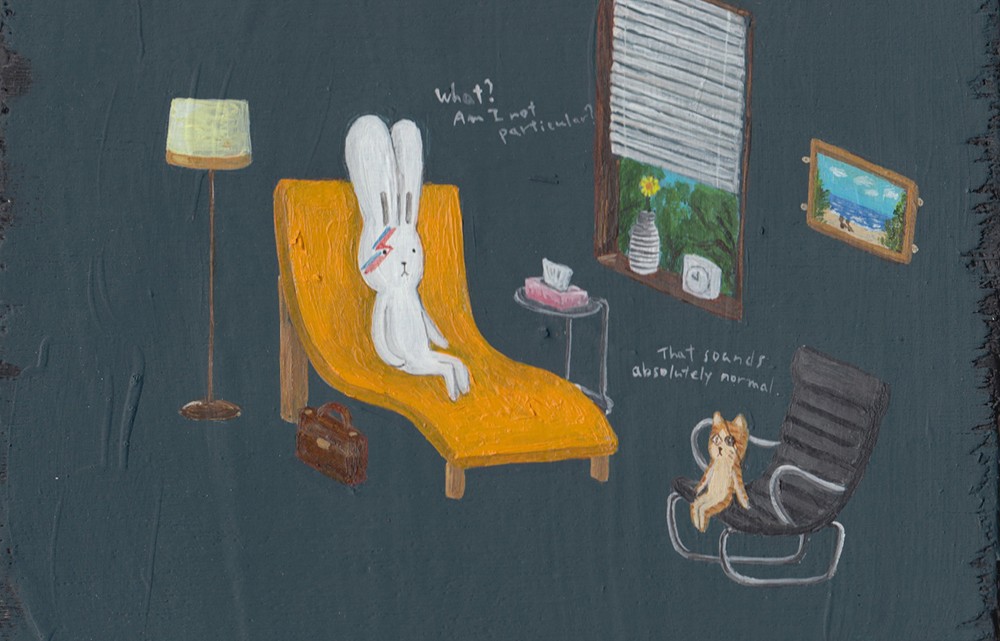

It is hard, at first, to detect any bravura in Atsushi Kaga’s work: what with paintings of bunnies, raccoons, donkeys, and the frequent appearance of the Star Wars characters Yoda and Darth Vader, is it possible to glean anything beyond the lessons of a modern animal fable more suited to a child than to a critical eye? That’s where things get interesting.

Atsushi Kaga. “Fast lane and slow lane,” 2014. Acrylic on board. 23 x 32 cm

Kaga’s solo exhibition I am here with you at the Jack Hanley Gallery has no overarching moral imperative like those within the stories of Aesop or the Grimm brothers, but instead portrays a barren landscape located within a moral vacuum. His fluffy animals experience eating disorders, depression, drug addiction, and petty crime. Lines of dialogue, painted in the style of a graphic novel, reflect a startling self-awareness in Kaga’s characters (some based on people in his real life, others completely invented), even if their faces don’t seem to reflect a great deal of physical gesture. Most of these scenarios include “Usacchi” (or “Bunny”), whom Kaga describes as a realization of his alter-ago, interacting with a slew of figures in order to demonstrate the bleak prospects that await the grownup versions of childhood, anthropomorphic friends. Think of it as a kind of cartoon-character rehab colony.

Atsushi Kaga. “Orange eaters,” 2015. Oil and acrylic on canvas. 152 x 122 cm

It is Kaga’s paintings on canvas and paper that truly engage. There, we see a series of unfortunate narratives that are simultaneously witty, straightforward, and melancholy. On a colorful banner, Usacchi’s self-doubt reads out, “I used to be philosophical when I was younger. But what happened to me now?” Yoda appears in a constant state of wearied resignation, saying things like, “I am ready. Take me now” and “When am I going to die?” The larger works show a heist in progress in a ‘40s pulp mystery story-spotlight, peacefully communing with nature, and Yoda (once again) deep in thought, is surrounded by names of major pharmaceutical companies. Altogether, the works are charming and wistfully sad, and Kaga subtly extracts a faint amusement from his audience where it could easily plunge into an inescapable psychic void.

Atsushi Kaga. “I am here with you,” Installation View. Jack Hanley Gallery

The exhibition layout is fairly generic and disappointingly predictable. An entire wall of the gallery is set up in the style of the classical Salon: small-scale “portraits” and “vignettes” are hung very close together, nearly floor-to-ceiling, while the opposite wall holds large-scale works with natural landscapes and tightly-framed action. Several sculptures are perched in the center of the gallery, made from textiles, clay, and paper. A single video screen, mounted just above the floor, presents a series of short films where Kaga’s animal characters are substituted by human beings. The brilliant, deadpan humor of the paintings doesn’t translate as effectively in the sculptures, which end up reading like a series of confusing, middle-school dioramas, while the video works prove to be little more than momentary hooks for popular attention. Nevertheless, Kaga’s commitment to a character story that has spanned over a decade is impressive both in its candor and its technical execution. Any distractions are quickly sidelined in favor of his two-dimensional work, where his viewers appear most engaged. Collectors, curators, and passersby love Kaga’s work not only for its clean, simple compositions, but also for its ability to quietly pierce the garish, flashy insanity of the “real” world with the observations of an introspective loner.

Atsushi Kaga. “Usacchi and Kumacchi in summer,” 2014. Acrylic on board

34 x 30 x 2 cm