I see you, in my mind’s eye, moving along a diagonal axis. You said something to this effect in an interview a few years ago, no?

Yes, at the beginning of 2013, I set out to have a year of diagonal thinking. Maybe this makes me sound like a lunatic or a child, but I picture different modes of thought having different shapes or gestures.

Are you a synesthete or is this an intellectual picturing?

It’s just an imagining. I’m not a synesthete. I think most people who claim to be are lying.

You wanted to take some time off and switch directions. Hold on, let me find it . . . “I’ve decided to take roughly a year for myself and—the way I’m articulating this in my mind, I’ve been moving in a straight line, and now I just want to be able to move diagonally.”

This is all true, but I hate how I said it.

Why?

“For myself?” What do I mean there? That, until then, time had been for someone else? I think that’s silly, but maybe it’s indicative of how I was feeling at the time—at the mercy of others or something.

Well, it stuck with me initially because it was lucid and interesting, and later because Diagonal Press was born shortly thereafter.

Only nine months later! It gestated just like a human baby!

A diagonal baby! Let’s start with a few points on the line and explore the latest with the press, especially as this interview coincides with the New York Art Book Fair. Are you still moving along a diagonal axis?

Yeah, I mean hopefully! Like I said in that interview, going into this venture I felt like I’d been moving in sort of a straight line. And that over time, ironically, that had led me a little astray.

Too formulaic or calculated?

Maybe just naïve. I started having exhibitions and selling artwork when I was pretty young—24 (now I’m 34). And initially I was trying to proceed in a rather predictable way: to make a living doing what I loved, to make better and better art, to have better shows at increasingly interesting places. You know, “progress.” I’ve never cared about money, but suddenly there was a lot of it being traded for my paintings on the secondary market. That aspect of things took on a life of its own in the last five years, at times a very ugly life. One of the worst features of this is that I used to give a lot of art away to benefits, but it came back to bite me so many times with people flipping things at auctions that I basically can’t anymore. And I resent that because I feel like, what’s the message here? Don’t be generous? That’s so upsetting. Now I mostly just want to give to animal rights organizations anyway, and they don’t usually have art auctions so that works out fine. But this is all to say that all this money part of things that I had no control over seemed to undermine real conversations I was trying to have. In interviews people would ask me about auction prices rather than about actual artwork. I hated it being such a dominant part of the discussion, so I kept finding myself evading the topic—sidestepping it—which might be considered a lateral motion.

So, at the beginning of 2013, I found myself very unhappy with all of this. Like my position in the business of art didn’t represent my values on things like income inequality, capitalism, and greed—that this had somehow come about without my consent—and I was being a coward by not addressing it. Neither direction of motion felt right to me anymore, so this was the beginning of me asking myself to think diagonally—just trying to come up with a new way of moving through all of this that isn’t just about moving ahead, but also isn’t avoidant.

One thing I was sure of was that I didn’t want to quit making and showing art, which has been the solution for some people with similar feelings. And I didn’t want to act cranky or generically antagonistic. To me that’s just too simple and uncreative. I wanted to put my ideas into a form that could be afforded by a lot of people, not just the wealthiest in the world, and I wanted for people to exchange their money for this work only if it actually interested them and offered them something psychically rather than monetarily.

So the press was the answer.

It’s just me taking a hearty stab at an answer. One of many necessary answers, and I’m not going to stop trying to think of others. One of the beautiful things about printing is that you can make as many as you want! I can’t make more than one of the same painting because of the way I paint, so they will always be unique. And I think there is value to unique work that human hands have touched for hours, transmitting something energetic from person to person. This is not a dismissal of that by any means. There is real magic in there. But there’s no need to only work that way.

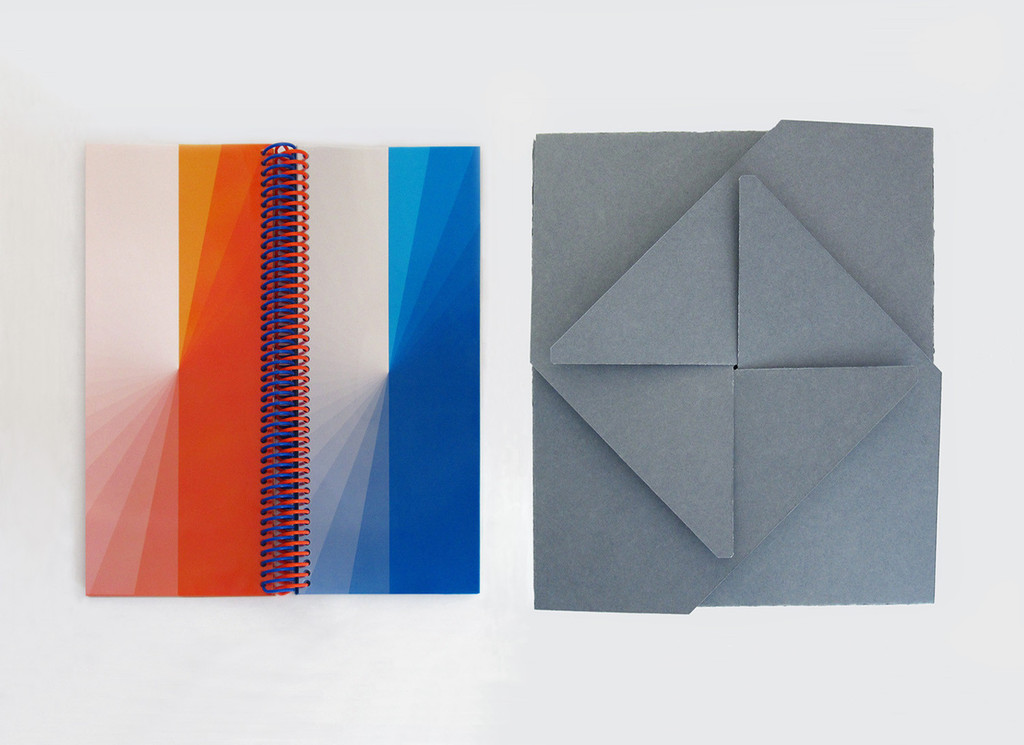

Z Helix (detail), 2014. Book: Indigo print on 4 mm transparency film, bound with two 16 mm spiral binding coils. Box: E-PLUS Heritage corrugated. Book: 11 x 9.5 x .63 inches. Box: 12 x 10.25 x 1 inches. Courtesy of Diagonal Press. Photograph by Chelsea Deklotz.

What was your first public appearance like as the press and not necessarily as Tauba Auerbach?

At the first Printed Matter fair I just kind of just jumped in. I made 14 specimen posters for fonts I’d designed, three symbolic pins that corresponded to them, and three books. I went into it wanting to structure the monetary aspect of it in a way that forced the type of exchange I was just talking about—a genuine and substantive one that’s not about resale. So I thought that doing everything in open editions and not being signed or numbered might be a way to enact that. Maybe it would build a secondary market out of the equation because people could come to the press for the original price. It was interesting being at the table the first year, because several people walked away when I told them the editions were open and that nothing would be signed or made distinct from other copies in any other way. It was both insulting and deeply affirming at the same time.

![[left] Stone Cactus Twist Pin, 2013. Diecast zinc alloy and soft enamel, 4 x 0.5 inches. Double clutch closure. Courtesy of Diagonal Press. [right] Japanese Maille Pin, 2015. Diecast zinc alloy and soft enamel, 3.1385 x 0.55 inches. Double clutch closure. Courtesy of Diagonal Press.](https://www.sfaq.us/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/0421_Enamel_Pin_Twist_web_2_1024x1024.png)

[left] Stone Cactus Twist Pin, 2013. Diecast zinc alloy and soft enamel, 4 x 0.5 inches. Double clutch closure. Courtesy of Diagonal Press.

[right] Japanese Maille Pin, 2015. Diecast zinc alloy and soft enamel, 3.1385 x 0.55 inches. Double clutch closure. Courtesy of Diagonal Press.

How has your approach to the fair and press changed since then?

This is the third year I’ll be doing the NYABF, and my objectives are the same, but some things are going to be different. I’ve always been someone who can’t help but leave stylistic fingerprints all over everything I make, even in different media, which I consider a strength at times and a weakness at others. In this instance, I think it’s something I need to work against. It’s not that I want to totally efface my natural aesthetic, but I want to keep this whole thing constantly shifting a little bit, so I really don’t want it to be branded. Everything seems so branded these days. So for example, there’s a diagonal wiggly line that I’ve been using from the beginning as something like a logo—that’s going to slowly disappear, and other line treatments will constantly be developed and put in its place. For the fair I’m making flags from some of these, a few of which are 2D drawings of 4D linear ornaments I’ve been working on for some paintings.

Will you author those treatments?

Yeah, these lines are something I’m kind of always working on, like the fonts. In fact, some of them are in the fonts. Others show up in sculptures.

Is there space for diagonal collaborators?

Possibly! I’m open and don’t want to be rigid. One epiphany I had while developing this project was that to conflate integrity and rigidity is wrong-headed. For now the press is an outlet for ideas I’ve had over the last few years but haven’t known how to present, and for “exhibition catalogs,” which in my case will continue to be artist books with no text or photos . . . just other pieces of artwork in book form that offer an ancillary perspective on the works in the show. I currently only have one plan for a book by another author, but details of that project shall remain secret for now.

Which people and projects populate your trajectory and serve as sustained inspiration in the diagonal department?

Charlotte Posenenske

Moondog

I can see why Moondog would make your (very short) list—those wild time signatures, homespun instruments, incredible cloaks, and music written in Braille.

Moondog is my man. I listen to his music on my bike almost every day.

I’d like to know more about Reciprocal Score, your recent exhibition with Posenenske in Rome. Although she’s no longer living, was arranging her metal and cardboard sculptures alongside your weave paintings a collaborative process?

This show was such a positive experience. First of all, it brought me to Rome a handful of times, and after New York, Rome is my favorite city. The show was not easy, though, because I was collaborating with a dead person, and a person I respect very much, so I wanted to do her proud. I worked extremely hard to inhabit Posenenske’s thinking as much as my own the whole way through. That’s why it’s called Reciprocal Score, where neither and both are the initiators of the dialog. It’s like those canons Bach wrote for two people to play sitting opposite each other reading the same sheet music laying on the table between them. Table canons, I think they’re called. Oh, wait! This actually all connects, because I learned about table canons in a conversation with my friend Pat Higgins. He, his bandmate Sam Hillmer, and I have been having this rolling conversation about collaborating, in which I first uttered the phrase “reciprocal score” as a description of how we were trying work together. When I realized that this was how the Posenenske show was also functioning, I asked them if I could poach the phrase from our conversation for the title.

I really did go back and forth with Posenenske. I talked out loud to her a little bit when I was particularly uncertain. And when it was all done, I crawled into one of the tubes and left a little note to her on the inside. That’s something that Will Brown would probably zero in on, huh?

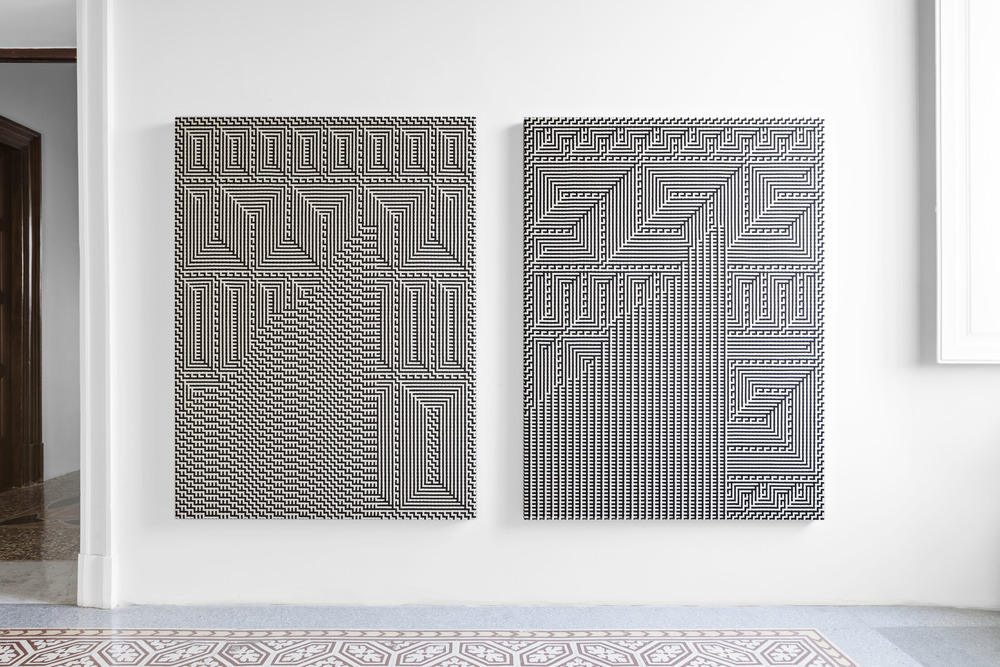

Installation view, Reciprocal Score (Tauba Auerbach and Charlotte Posenenske) at Indipendenza Roma, Rome, 2015. Courtesy of Indipendenza Roma and Standard (Oslo). Photograph by Vegard Kleven.

Installation view, Reciprocal Score (Tauba Auerbach and Charlotte Posenenske) at Indipendenza Roma, Rome, 2015. Courtesy of Indipendenza Roma and Standard (Oslo). Photograph by Vegard Kleven.

That’s fantastic. Will Brown is considerably less sweet than you, but you’re right that we’re interested in where the artist, artwork, and archive meet, especially when collaboration and materiality are involved.

I meant that you guys would probably dig this fact up, years later or something, and then locate that exact tube and install it somewhere clever. You guys nailed it with that car outside the Berkeley Art Museum.

Oh! Well, that’s nice of you to say. And yes, I wouldn’t be surprised if that tube ended up in a car outside a museum somewhere in Rome circa 2035 . . . Did you see her Artists Space show a few years ago? Was that your introduction?

Yes, that was the first time I saw her work in person. I went twice.

Posenenske was interested in systems and series, selling her artwork at its production value, and existing as firmly as possible outside commercial art world processes. Was she an explicit inspiration for the press?

I actually didn’t know this about her when I started Diagonal Press, so when I discovered that I was over the moon! It made me feel kindred with her, but I also saw along the way how we differed. She stopped making art and I don’t think I could ever do that, even though I respect her so much for devoting herself to research and social justice.

Yes, to impact measurable change via employment studies and union organizing. Given that you work in painting, weaving, sculpture, sets, costumes, books, musical instrument building, typeface development, calendars, clocks, mathematical symbols, jewelry, and photography, it’s hard to imagine you dropping out—where to? But is it always “art” that you’re making?

No, not always. But most of the time I feel that I’m doing those things as an artist. I don’t know if that makes any sense.

We’ve worked together at the Exploratorium in San Francisco and Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, CT, two American institutions not only outside the commercial art world but also primarily in a business other than the display of contemporary artworks and exhibition making—one a humanist project founded by a physicist and the other essentially a house museum. Are these particularly comfortable or exciting settings for you? And with so many interests outside the white cube, how do you evaluate taking on a project?

I really like working in settings outside of traditional art spaces. Like Indipendenza in Rome, which used to be the owner’s grandparents apartment. There are terrazzo floors and wallpaper in some rooms and the wear and tear of a time spent in there. I loved it. And The Glass House was a truly great prompt to make a sculpture specific to its setting. I liked that assignment, and the sand sculptures that came out of it went beyond that one show. That said, I sometimes like the white cube, too. It’s practical for me—some ideas are better tested in a clinical environment, and others aren’t.

Installation view, Tetrachromat at Malmö Konsthall, Malmö, 2012. Courtesy of Malmö Konsthall. Photograph by Helene Toredotter.

When is your next solo gallery exhibition?

My next show is in January 2016 at Paula Cooper in NY.

The last one was 2012?

Yes, so long ago. I’ve postponed this show twice.

How’s the break been?

To be clear, it wasn’t a break from working, just a break from exhibiting. It was wonderful and necessary.

Of course. What are you thinking about for January?

The helix. I think everything is a helix. Everything is spinning, and almost everything is moving in relation to everything else. So every path is helical. It’s also not, not a big deal that DNA is helical. I made the first two helix sculptures for my ICA show last year.

This magazine is now moving east, just like you did seven years ago. What does California, and San Francisco in particular, mean to you now? I know you very recently spent some time back home and it was . . . different.

San Francisco is a weird place for me now. I feel very lucky to have grown up there. I still feel like it’s my home, and I probably always will, but now it’s a combination of deeply familiar and totally unrecognizable. The mood has been radically transformed by all the tech stuff and somehow it’s simultaneously so stuck in the past. I don’t know how this is possible, but I think most people who really know the city would agree.

So I suppose San Francisco will always have my heart, but it lost my head a long time ago. My mind just turns to mush when I’m out there, which is very relaxing, but I don’t like it as a sustained state of being. I do better in a more hectic place, honestly. Dense, lots of different people, a little difficult.

As a young artist in the Bay Area, however, your mind wasn’t a hash sandwich. Your early shows at Jack Hanley were knockouts, super sharp and sophisticated. But a little groovy, too, now that I think about it. For one opening you installed a “trade table” at the front of the gallery where visitors could leave an object in exchange for a book that you made—the first 50/50 book, in fact. Visitors could leave whatever they thought was fair. That’s when Jack’s openings were 95% friend based. Although I can clearly see the parallels between the table and the press, does that endeavor now feel naïve, or on target, or both?

The trade table was a good experience and I would maybe even do it again. I think I would retain the right to refuse things next time, though, which I think is fair because the other person is not being asked to consent regardless of what’s offered. It would just be symmetrical that way. I sure received a lot of crap, but I also walked away with some amazing and thoughtful trades that I treasure, like a Penrose tiling mosaic from an old schoolmate, Brett Lockspeiser, and a drawing I did when I was five or six from an old art teacher. But material things aside, I just enjoyed the experiment. I wonder if the vibe would be different around the same kind of thing here. I noticed that at the 8-Ball Zine Fair in New York this year there were two publishers who were using a pay-what-you-wish system, which seems to be of a similar spirit.

I wonder about the line between rational and irrational in your work, the knowable and unknowable. What does belief have to do with what you’re up to? It’s not possible to visualize various concepts you’re interested in, so what are you aiming at with your work that ultimately manifests visually?

Right now I think about trying to make art that is entheogenic. Entheogens are molecular compounds that induce altered states of consciousness, which are said to bring the user into contact with “the divine.” For me the divine is everywhere, the goddamn amazingness of the universe: its complexity, order, and mysteriousness. I’m talking about everything from the amazing architecture of something like a shell, to things like dark matter, the bending of space-time, and whatever consciousness is. These are the things I think about, read about, and live in utter awe of. That, and my gratitude for being here and able to take it all in. So if I could have one goal for right now it would be to make something—an object, an image, a sound, anything—that acted entheogenically, bringing a person into greater contact with whatever might be divine for them.

Related to that, I’ve recently been meditating on the idea that my 3D self is entirely in contact with my 4D self. Every bit of it, even the deepest interior bit. I sit and focus the contact. Maybe that sounds silly, but it brings me into an interesting state. I’m thinking of publishing a little booklet of this meditation’s rationale for the book fair.

Firstly, you should make that booklet. Secondly, it’s awesome and inspiring that your entheogenic explanation could just as easily have come from Barnett Newman. And not that this interview should appear in Modern Physics, but it sounds like you see what’s out there as fundamentally ordered.

It seems to have rhythm and pattern, so yes, order of some kind.

This makes me wonder about art that can be proven or is itself a proof or solution. Someone once called Calder’s work “perfect solutions.” How does that sound to you? Exciting? Limiting? I’m not only thinking about your work with mathematicians that aids in the service of solving, but also your ability to transform your ideas into form with such precision—like the press, for example.

Such a good question. A perfect solution sounds like a bit of a cul-de sac to me. I don’t think I want that. I like the idea of proving little things, and incorporating those discoveries into bigger, open questions. But maybe art is better as a speculation or proposal than a proof.

How is your work like a proposal?

In my case, a proposal is like a noodle I throw against the wall to see if it sticks. Actually, the art is the throw, not the noodle. I make all kinds of wild speculations about hyperspace, for example, and I don’t do that because I think they are going to be “proven” and used by scientists, but because these ideas have become metaphorical for how I want to think, not just what I want to think about. That said, I really do believe that the great questions in science today all boil down to topology.

Topology? Shapes rotating, spinning, or stacking but fundamentally unchanging?

The “architecture of connectivity” is how I would describe it.

What’s the relationship between a diagonal line and 3D space?

I’ve been looking at a lot of space-filling curves this week, so my head is all aflutter with lines that approach being planes. I found this wonderful tool on Mathematica for mutating them. So I guess the line can exist in 1-, 2-, or 3D space, and, in my opinion, 4D space.

At first I saw all of this—the type of thinking I wanted to do, and the type of motion I wanted to make—as flat: a diagonal line drawn between perpendicular X- and Y-axes. But now I’ve come to see it as a representation of the Z-axis, like the diagonal lines in the drawing of a cube. So for me the diagonal line on a plane is a projection drawing of the dimension that comes off the plane.

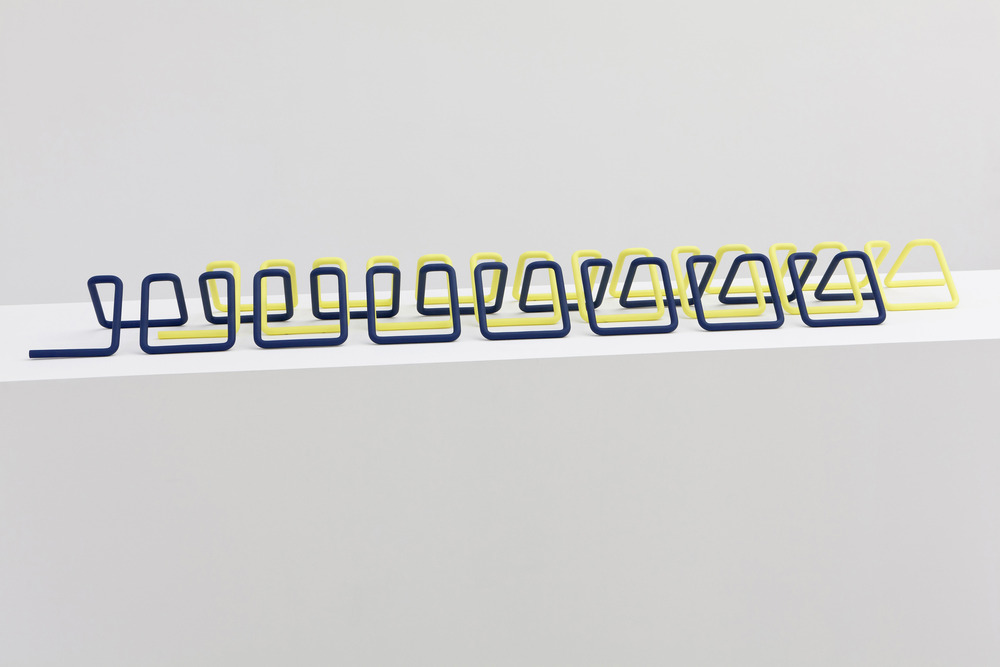

Knit Stitch, 2014. Stainless steel and powder coating, 85 x 16 x 6 inches. Metalwork at New Amsterdam Metalworks, Coating at Wicked Powder Coating.

Tell me more about your 4D self.

I think that consciousness is a 4D material. I should put “material” in quotes. To be clear, the fourth dimension in this case in not time. I mean a fourth dimension of space that runs perpendicular to the three that we know. If a sphere were to pass through a 2D universe, the planar beings would experience that 3D object as a series of circular cross-sections only . . . a dot that appeared as if from nowhere, expanded, contracted, and then disappeared. This is how a 2D being experiences something of a higher dimension passing through its world. All I’m saying is that consciousness seems to present the same way here—appearing as if from nowhere, expanding, contracting, then seeming to disappear. This might sound bonkers, but believe me, I have a book by a bunch of physicists speculating on what consciousness is, and there are much nuttier notions out there. So just like the circular cross-section of that sphere, we are 3D cross-sections of our 4D selves. Just passing through . . .

That’s a really interesting noodle, Tauba, and one more resonant with math and science than philosophy or new-age beliefs. Do you borrow at all from those disciplines?

I enjoy reading about math, learning about the history of science, and things like that. Some New Age thinking is legit, but I’m pretty allergic to the aesthetics.

Interdisciplinarity can feel a bit like creative political correctness and it can be hard keeping up with the latest pre-hyphen preposition: trans-, poly-, inter-, multi-, non-disciplinary. Broadly speaking, what do you think of disciplines? Does the personal and professional nature of disciplinarity inspire you or get in the way? How often, I wonder, do you write to folks in completely different fields with a query?

I don’t think much about disciplines and I find that a lot of people are working on the same interests but in totally different fields. I have been known to cold email topologists or write fan mail to mathematicians. Don’t laugh. Or do! They have mostly been very responsive and generous.

What’s the latest on your MIT residency and project with the incredible father/son duo?

Actually, Marty and Erik—who I’m collaborating with at MIT—are two of the people I sent fan-mail to. They don’t remember this and it wasn’t part of us becoming collaborators. I only revealed it to them recently once I felt I had proved I wasn’t a hack. We are having fun, making a font out of various ways to slice the surface and unfold a cube, and also a video of a 4D shape that I’ve been wanting to visualize but which remains elusive to me.

You told me you were interested in non-orientable surfaces so I looked up a definition, which has kept me baked for days: “A surface is non-orientable if and only if you can find a Möbius band inside of it, like we did in the Klein bottle and the projective plane. A surface is orientable if it’s not non-orientable: you can’t get reflected by walking around in it.” Care to comment?

That last bit is utterly confounding. Are you allowed to define something by saying its not it’s opposite?! That’s ridiculous.

The Möbius strip is non-orientable, true, and understanding it does give insight into all non-orientable surfaces. But now I realize that I don’t have a good alternative definition! I should think about that. I have a number of glass Klein bottles in my studio and those are also non-orientable, like a 3D equivalent of a Möbius strip. They are bottles that pass through themselves in 3D, but wouldn’t in 4D, and have no inside or outside. They are also minimal surfaces, which means they have a mean curvature of zero.

How about architectural ornaments, something else I know you’ve been interested in lately.

Oh, I’ve been obsessing over architectural ornaments! There are a few motifs that come up in almost every culture, in every part of the world. And I can’t help but think that these shapes, which are essentially different types of waves and helices, have stuck with us or we have stuck with them for a reason more powerful than convention. Maybe they resonate because they bear some resemblance to the fundamental structure of matter and space. So, like that classic Greek meander fret pattern, it’s just a bunch of little twists. And like I said before, I think everything is a helix, so in my opinion that pattern resonates with a deep visceral connection we have to rotation combined with translation. It’s like a drawing of something microscopic and macroscopic at the same time, and we exist between these two scales where this motif arises. Look at the convection patterns on Jupiter. They are the same structure as the Greek “meander” or “key” frets. Now I’m looking at a lot of swastika books.

Although I’m aware of its harmonious roots, I still haven’t managed to live with the swastika paperweight I picked up in India several years ago.

I guarantee that if you begin to research the glyph its benevolent associations will begin to outnumber the evil one. You might even be able to enjoy that paperweight. Is it a swastika or a sauvastika anyway? I think the same way about the swastika as I do about that architectural ornament—that it has been a resonant symbol because it taps into something deep and fundamental—the rotation of all things. I now also see it as the end or cross-section of a helix.

Sauvastika?

Where the arms go the other way. The mirror image of the swastika.

Did you ever learn to drive stick with your dad (who races cars in addition to practicing theatre design, architectural lighting, and audio-visual consulting)?

So far I’m not very good and I haven’t tried in a long time. Trying to learn stick was one of the most frustrating experiences of my adult life. I think of myself as mechanically minded and well coordinated, but I just really sucked at it. But maybe that’s because I hate driving. I let my license expire almost three years ago and I don’t miss it at all. I’m all bike all the time right now . . .

Do you ever reach out and propose ideas to people/places?

I just did it today! I don’t know how well it went over, but it was worth a shot. In general it’s not something I do very often.

Did you get where you needed to go with sand?

I think those particular sculptures are done, yes, but I have a new idea with sand that I want to test out. I got to one of the stops on the route, but there might be a few more.

Slice/Wave Fulgurite III.I, 2013. Sand, granite, glass, resin, opal and garnet, cast at Factice. Glass and spray-lacquered wooden plinth. 2.375 x 42 x 9.75 inches. Courtesy of Standard (Oslo). Photograph by Vegard Kleven.

Slice/Wave Fulgurite III.I, 2013. Sand, granite, glass, resin, opal and garnet, cast at Factice. Glass and spray-lacquered wooden plinth. 2.375 x 42 x 9.75 inches. Courtesy of Standard (Oslo). Photograph by Vegard Kleven.

Where are you at with randomness?

Over it. Under it. Not even interested anymore.

Do you like to swim?

Yes. I like being upside down underwater. It makes me uneasy and scared in a good way.

Sculpture! Sculpture?

Both exclamation and question. Indeed.

A search?

A search, a wander, a dream, a delusion, a trip, a death.

What sort of question is best answered as an image?

A sound.

What sort of question is best answered as a final question?

This one.

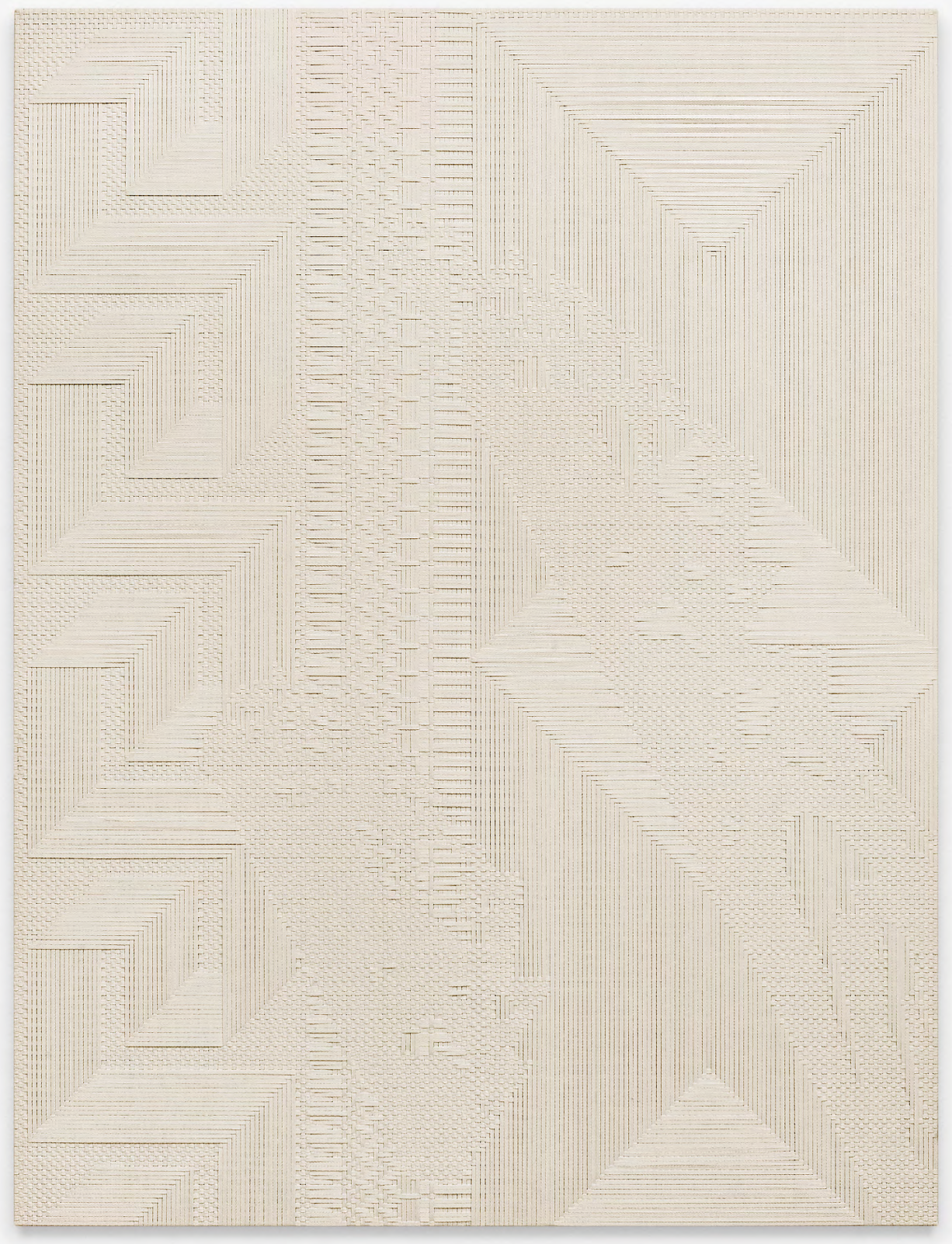

“Chiral Fret / Slice,” 2014. Woven canvas on wooden stretcher. 72 x 54 inches. Courtesy of Standard (Oslo). Photograph by Vegard Kleven.