Julian Hoeber: The Inward Turn

Jessica Silverman Gallery

488 Ellis St., San Francisco CA 94102

November 6 – December 19, 2015

Upon entering Julian Hoeber’s solo exhibition, The Inward Turn, the viewer may wonder whether they have walked into a museum of anatomy, or an architectural firm, or perhaps into a workspace for science fiction experimentation. In a sense, all of this is true. The impetus for the work (all new and created this year) is deep introspection, as noted in the exhibition’s title. Hoeber’s methodology is akin to a Möbius Strip: its curved information highway, a channel for thought and ideas that continue repeatedly, thus never really finding a solution or a new destination, but rather loops-the-loop for eternity. Likewise, this lack of destination is reiterated in Hoeber’s departure point for the work that he calls Going Nowhere, which is based upon his ideas for a speculative airport—meaning an airport that will never exist. Consequently, the airport can be equated with a Möbius strip where the passengers arrive and leave, only to return to the same airport again. With this futility in mind, it is no wonder that Hoeber is currently occupied with issues of place and how we navigate in the world, as seen in the many architectural and bodily references throughout.

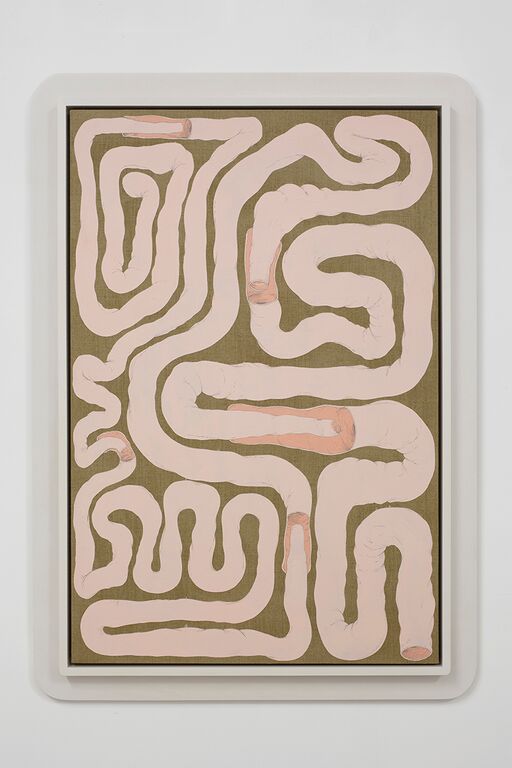

Julian Hoeber, Intestinal Floorplan/Security Apparatus, 2015. Flashe and acrylic on linen in artist’s frame, 49 x 35 in. (125 x 88 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery.

Along the wall a series of studies outline ideas for floorplans or plumbing infrastructure for the airport. Ruminating Elevation 01 and 02 feature sinewy, broken-bone shapes laid in formation. Implying thought and contemplation; the images recall bizarre structures from the 1973 animated surrealist film Fantastic Planet. Spiral Floorplan and its counterpart, Intestinal Floorplan/Security Apparatus, show pale pink tubes laced along the surface, with darker pink segments revealing sliced interiors of the innards. Each illustrates the human intestinal tract as a means for travel as well as for protection. Another series, titled Thought of Forms/Forms of Thoughts 01 – 08 are inverse and converse form studies with delicate wooden stick armatures encased with Japanese kozo paper and sealed with shellac. They look like fragile bones in one instance, and resilient architecture in the next. Nearby, Negative Space of Organ (Core) protrudes above waist height, as if it is a speaker from George Orwell’s 1984, waiting to announce crowd formations or group thought speeches. Similarly, Brutalist Organs appears to be an audio device. Two large, stacked dumbbell handles—one in pastel pink, the other in a dusty rose shade—solidly take their rigid stance on a beautifully constructed mid-century modern stand with a glass top. When viewed from the side, two unmistakable hollow orifices confront the viewer.

Julian Hoeber, Negative Space of Organ (Core), detail 2015. Sculpture: OSB, pine, foamcore, kozo, shellac, and hardware, Pedestal: Maple, glass, catalyzed oil finish, Sculpture: 25 x 25 x 22 inches (63.5 x 63.5 x 55.9 centimeters), Pedestal: 38 x 28 x 16 inches (96.5 x 71.1 x 40.6 centimeters). Courtesy of the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery.

Scholar’s Rock Proxy is the most sublime piece on view. Its decaying appearance is enhanced with white smears of pigment streaking through a black cement surface, scattered with torn and jagged holes. The shape is that of a thick folded page, or a rippling cross section of a topographical slice of the earth. In Chinese culture, a scholar’s rock is a natural formation, reveled for its breathtaking, incomprehensible beauty. It is typically displayed as a viewing stone, placed in gardens as an emblem of supreme aesthetics. Likewise, Scholar’s Rock Proxy is away from the other works, as if in a landscape periphery. The structure is placed on a low, exquisitely constructed table of stout legs arranged in a honeycomb formation. One has to kneel as if in a gesture of meditation to get a better look at its detail. Unusual from the rest, this piece is exemplary of aesthetics and existentialism combined.

Julian Hoeber, Scholar’s Rock Proxy, 2015. Sculpture: pigmented and unpigmented ultracal cement, and acrylic lacquer, Pedestal: Cherry wood with catalyzed oil finish and MirroView glass, Sculpture: 18 x 22 3/4 x 30 inches (45.7 x 57.8 x 76.2 centimeters), Pedestal: 12 1/2 x 29 x 46 inches (31.8 x 73.7 x 116.8 centimeters). Courtesy of the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery.

Hoeber’s earlier works relied heavily on formally precise geometric abstraction, architectural typography, Op Art tricks of the eye, and vibrant, saturated color. For this show, the subdued color palette in charcoal and silvery greys, rosy and peach pinks, creams and beige is disarming, yet primly uncomfortable. Overall, the installation exudes a seductive corporeality, referencing bones, intestines, belly buttons or tendons. Metaphorically, the body can be seen as a place, in that it houses organs, brain, blood, a network of veins; where air enters and passes through, where food is consumed and then expelled as waste. Likewise, Hoeber’s fictitious airport can be understood as synonymous with the body—a vessel where people enter and leave, arrive and depart. It seems that Hoeber’s commitment here is to phenomenology rather than logic; where fiction can be a profound metaphor for reality. Perhaps viewing the work can bring one closer to personal awareness, rather than getting caught in a Möbius Strip of banal routine.

Julian Hoeber, The Inward Turn, installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery.