Home Land Security

FOR-SITE Foundation, National Park Service, Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy, Presidio Trust

Fort Winfield Scott, the Presidio, San Francisco

September 10—December 18

Home Land Security, a group exhibition presented by the FOR-SITE Foundation on the grounds of the Presidio, assembles works by an international roster of 18 established artists who are preoccupied with figuring the human cost that the pursuit of security exacts. What is security? What is spent in its pursuit, and what is sacrificed?

Curators Cheryl Haines and Jackie von Treskow of the FOR-SITE Foundation previously worked together on the exhibition @Large, which brought the art of Ai Weiwei to Alcatraz. Like that show, Home Land Security projects the foundation’s expansive vision of a public art that is unforgettably situated in place.

At Fort Winfield Scott, Home Land Security occupies a series of low Cold War-era structures perched at the edge of the Presidio cliffs. The Nike Administration Building, the largest of these, houses works by Shiva Ahmadi, Tammam Azzam, Tirtzah Bassel, Yashar Azar Emdadian, Díaz Lewis, Liza Lou, Trevor Paglen, Michele Pred, Bill Viola, and Alexia Webster. Batteries overlooking San Francisco Bay hold works by Al Farrow, Mandana Moghaddam, the Propeller Group, Luz María Sánchez, Do Ho Suh, Krzystof Wodiczko, and Yin Xiuzhen; Shahpour Pouyan’s sculptures occupy the Fort Scott Chapel nearby.

Tirtzah Bassel, Concourse, 2016. Duct tape on wall.

Immediately upon entry viewers encounter Tirtzah Bassel’s Concourse, which transforms the long, low room in which it is situated into a plausible facsimile of an airport security screening facility while imposing only the most casual traces in passing. It’s drawn with duct tape on the bare concrete walls, but the illusion it generates reaches startling heights of verisimilitude. The murals provide a 3-D illusion that continues real space for a trompe l’oeil effect—not unlike the ones Mantegna painted in the fifteenth century, except that those murals celebrated and exalted the positive potential of what it could mean to be human, while the all-too familiar ritual Bassel’s characters undergo does pretty much the opposite.

When individual characters emerge, they look familiar. The body language of the guy removing his shoes and belt is entirely relatable, even though his head is comprised of nothing more than a few tape fragments that bear no resemblance to any part of the human body when seen up close. Bodies queue, dragging their rolling luggage, and when they get to the front of the line they assume the positions required of them. A dark-skinned woman stands to be searched, her arms hanging limply at full extension. The TSA agents bustling at her feet stand out because of the blue latex gloves they wear to handle travelers’ bodies, rendered here in what appears to be blue painter’s tape. It’s hard not to be reminded of the defiant protagonist in Goya’s Third of May, except that the stakes of the whole enterprise have been diminished. Marx’s aperçu about history repeating itself, “first as tragedy, then as farce” comes once again to mind; security theater, indeed.

Tirtzah Bassel, Concourse, 2016. Duct tape on wall.

Farce and theater are predictably recurrent themes. That said, some artists here eschew satire, working instead directly with participant-viewers and people dispossessed through violence. The Chicago-based duo who make art under the name Díaz Lewis invite viewers to collaborate in activism on behalf of detained immigrants by making pillows as part of their 34,000 Pillows Workshop. Sewing machines, trimmings, a colorful pile of donated fabrics and cheerful instruction by exhibition docents are provided.

Alexia Webster, Bulengo Studios, from the Refugee Street Studio Project, Bulengo IDP Camp, D.R. Congo, 2014-ongoing; digital archive prints.

South African photographer Alexia Webster’s large portraits were made in the Bulengo refugee camp in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Her sitters, who range in age from babes in arms to the very old, pose singly, in pairs, or in family groups in front of colorfully patterned backdrops; Webster bathes them in gently revealing light. The prints, tacked up on bare walls, are reproduced at or near life size. When viewers enter the gallery these human beings with their mostly stoic expressions command our attention, giving the impression that they are looking deep into our eyes; we viewers, stung, have no decent option but to look away.

The video projections in Bill Viola’s Martyrs series embrace allegory in lieu of direct encounter. There are four martyrs depicted here, one for each of the primal elements. Exquisitely controlled images move at a glacial pace; elemental transformations move either forwards or backwards in time to drench, scorch, and rattle the martyrs’ suspended, floodlit bodies. Images are projected on the room’s four walls in a way that confronts viewers with their limitations. Moment to moment, the impulse to watch involves literally turning our back on other possibilities. Martyrs’ transformations remain inaccessible in their totality. These constraints figure something like original sin. Viola reminds mortal viewers that that our ability to see, like our ability to understand, is ipso facto limited.

In contrast to this gravitas, French artist Yashar Azar Emdadian brings an element of absurdist comedy to the video portrait by having himself filmed shaving his body hair while standing on a heirloom prayer rug in front of the Tuileries palace in Paris. Emdadian presents himself as a relatable Everyman who, like many of the rest of us, lives suspended between different sites and cultures. His portrait is full of poignant details, from the soft belly he exposes to the tell-tale single pants cuff that says he bicycled to the Tuileries. That palace, which entirely occupies the background, exists as a monument to an ancien regime culture that is now decisively other, its values so alien to those of our contemporary society that it might as well have been dropped into the shot from outer space. Emdadian’s video asks: How do we seek to purify ourselves? How do we seek to fit in? In expectation of what reward?

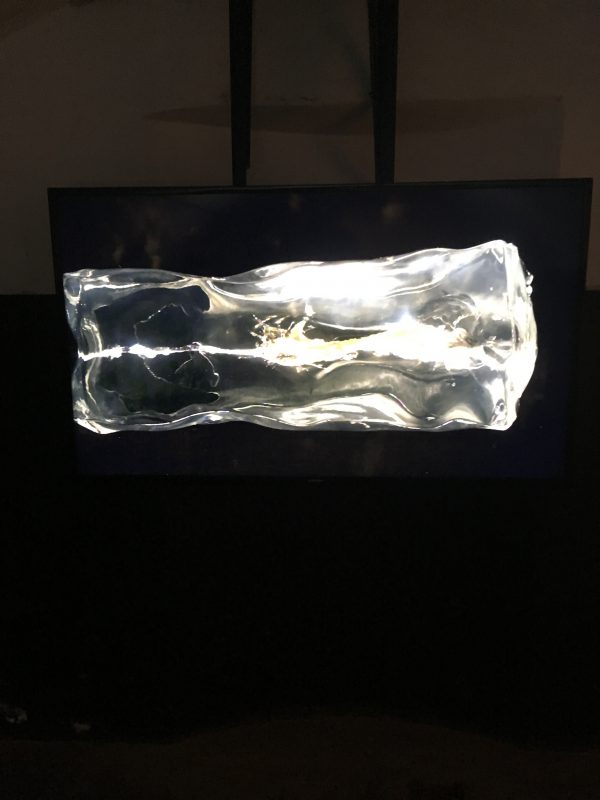

The Propeller Group, AK-47 vs M16, 2015; fragments of AK-47 and M16 bullets, ballistics gel, custom vitrine, and digital video.

In Battery Godfrey the Propeller Group revisits the subject of global conflict with a piece that demonstrates exactly how automatic assault rifles visit violence inside human bodies. The video, shot in extreme slow motion, shows a slab of quivering translucent gel buckling, ballooning and distorting as it takes simultaneous bullets from both ends. Across the room, the slab itself rests spotlit in a vitrine. We learn that this material was developed to model the behavior of living human or animal tissue when disrupted by bullets that enter flesh at an average velocity of 710 meters per second. The putative point of this exercise is to compare the merits of the assault rifles associated with the Cold War powers: the Soviet AK-47 squares off against the all-American M16 in a hideous parody of the product comparisons featured in ads for floor cleaners and antacids. Rather than getting caught up in the Cold War rivalry, viewers are likely to linger gobsmacked by the extreme nature of the devastation on display. The writhing gelatin slab seems about to turn itself inside out, as if it were undergoing some violent parturition or mitosis. Watching this at 100,000 frames per second is like watching the genesis of a new, alternative gun-based life form.

Al Farrow, Mosque III (after National Mosque of Nigeria, Abuja), 2010; “tank-killer” missiles, bullets, brass, steel, and trigger.

In the adjacent space, Bay Area-based Al Farrow shows miniature houses of worship built from repurposed guns, bullets, steel shot, and “tank-killer” missiles. His church, Revelation I, sits on a plinth apart from Mosque III, a scale model of the National Mosque of Nigeria. The juxtaposition is unflinchingly binary: religions and cultures self-segregate, securing adherents into houses of worship behind barricades that literally bristle with armaments. On one hand the installation seems to parody the emergent order epitomized in the global revival of ethnic nationalism and neo-fascist movements, aka the “alt-right.” On the other hand, with more than 300 million guns in the United States at last estimate, perhaps Farrow is simply proposing a functionalist approach to building that makes the most of whatever local materials are available in bulk.

Across the street, the Fort Scott Chapel houses five weapon-shaped steel sculptures from Iranian artist Shahpour Pouyan’s Projectiles series. The sculptures hang suspended from the chapel ceiling. At close range, it becomes possible to see that their steel surfaces are covered with intricate embossed designs. Passages of Arabic calligraphy alternate with intricate patterning that figures nature with images of twisting foliage and vines—images of organic plenitude that are somehow genuinely shocking to encounter in this context. Every inch of these sculptures is sharp and potentially injurious; they seem to be all blade, like Sadean torture machines conjured in some nightmare fetish zone to please a refined Islamophobic—or -philic—clientele. Grouped in mass, the sculptures dominate the space around them, to the extent that their presence here really does look like an occupation of sorts.

Shahpour Pouyan, installation view: one of five works from the Projectiles series: Untitled 1-3, 2016; Untitled 4, 2014; Projectile 10, 2013. Steel, iron, and ink

However, nothing is precisely what it seems—starting with the beautifully proportioned space of the chapel itself. The space is nondenominational, but the effect can be quite Christian when shafts of sunlight come beaming through stained glass to cross the oak-paneled, octagonal space. On a sunny, blustery November day the California sun shone through the gold-and-white glass in a pattern that evolved as it responded to the tossing of the eucalyptus trees outside. The architecture seemed exquisitely responsive to place, which turned out not to be the case; it was actually built according to a standard plan designed for mass production by army engineers whose names went publicly uncredited, just as the concrete batteries across the street had been. Identical chapels exist at military camps across the nation.

In that space, Pouyan’s sculptures come across as even less straightforward. Jorge Luis Borges once noted, citing Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, that the Quran, “the Arabian book par excellence,” contains no camels; if there had been any doubt as to the authenticity of the Quran, he writes, “this absence of camels would be sufficient to prove it is an Arabian work.” Following Borges, the superabundance of metaphoric camels here should arouse our skepticism, because the rigor and ferocity of the militaristic aesthetic Pouyan dreams up in these sculptures is over the top—a fever dream of the east that’s part Hollywood’s Son of the Sheikh, part ISIS black flags, accessorized with the trappings of the hunky Levantine avatars in Assassin’s Creed. One of the virtues of Pouyan’s work: it makes it possible for us to understand the seductive power any death cult can exert, given the right circumstance. This is true not in spite of but because of the fact that the sculptures are pure theater, like so much else having to do with security.

Shahpour Pouyan, installation view: one of five works from the Projectiles series: Untitled 1-3, 2016; Untitled 4, 2014; Projectile 10, 2013. Steel, iron, and ink.

That statement is in no way meant to be dismissive. Home is difficult to define, but surely it remains the place where we learn what it is to feel safe—or not. Feelings about security are founded in primal narratives about the defense of the home. They are vested in atavistic allegiances that predate personal identity: tribal identities and sacred sites, blood and soil.

Art about security is a natural fit, as it turns out. Security is largely a matter of perception: it is a feeling before it is anything else, and that feeling can be engineered, leveraged, and sold. In fact, there is no security without theater—least of all in the realm of citizens’ daily experience, as this exhibition makes clear.