Noam Rappaport: Dogleg

Ratio 3

2831 Mission St, San Francisco, CA 94110

January 16 – February 27, 2016

Enter the gallery and you encounter a profusion of rectangles arranged in diptychs and triptychs that appear to lean against each other, whose depressed and raised areas are formed by the addition or subtraction of layers of paint. Also, and just as enlivening, are small monochromatic pieces that look like sculptures on the white expanse of the walls. This is Dogleg, Noam Rappaport’s latest solo exhibition at Ratio 3, in the Mission District, in the cavernous space of a former fabric store.

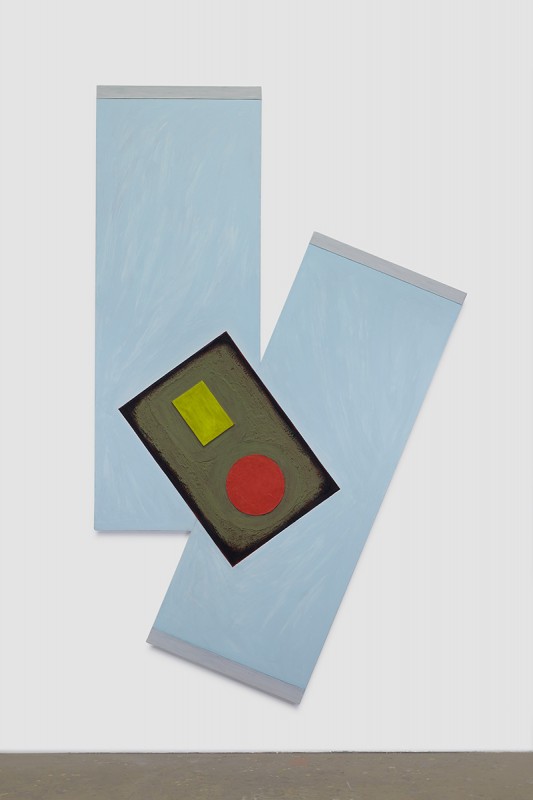

Noam Rappaport, Dogleg, 2015. Oil, acrylic, high-density foam, paper, canvas, 90 x 55 inches. Courtesy of Ratio 3.

Recently, I became a Facebook friend of essayist Dave Hickey, whose book Invisible Dragon: Essays on Beauty (1993) pits the idea of beauty, which is usually subversive and based on what a group of people or friends decide is interesting and could be a bit dangerous, against the idea of the beautiful, which pretty much means behaving yourself and going along.

A “dogleg” is something crooked or bent, and Rappaport’s appreciation of asymmetry, economy, intimacy, not painting quite to the edges, is evident in his concern with materials and processes. Rappaport may combine, say, pieces of string, leftover bits of wood from his studio floor, a found tree branch with his irregularly shaped canvases. His approach evokes Wabi-sabi[1] and also “Provisional Painting” or “The New Casualism” which is a trend in painting where “the rising inclination of artists to explore the metaphorical implications of failure, imperfection and imbalance—the artistic significance of the off-kilter and the not quite right.”[2]

Raised in San Francisco, Rappaport lives and works in East Los Angeles via Williamsburg, Brooklyn. We corresponded over email about his work. I wondered if he started with a drawing to construct the forms, how much are the pieces planned, and how much is revealed as he works.

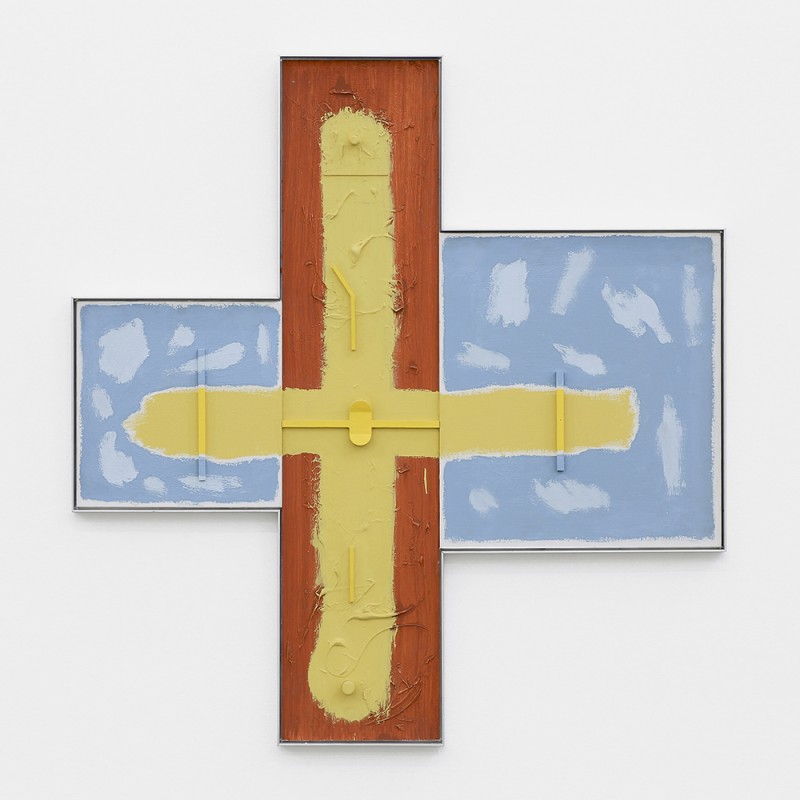

Noam Rappaport, HUB, 2015. Acrylic, canvas, wood, aluminum, 39 ½ x 37 ½ inches

NOAM RAPPAPORT: I attempt to dive in as soon as possible in the morning but am often waylaid by standard procrastinations or emails and chores. Those chores and studio clean-up often stumble naturally into making things. Drawing plays a role, but rarely in the sense that drawn plans result in anything you would recognize by the time the thing is finished….”

LANI ASHER: And the title of the show?

I was thinking about the connections between two or more forms as elbows, from that came “dogleg,” which is also a term to describe a bend or switchback in a path or route. I like how that relates to the thought processes involved in making things and the idea that getting from here to there isn’t necessarily a straight line. I used it as a title that nods to less-than-direct or perfect transitions and relationships.

Can you talk about the idea of diptychs and triptychs? Are they about duality or similarity? Is it a conversation with art history?

I am interested in what happens when two things are related to each other. The relationship itself becomes a third thing. These larger pieces only look like diptychs; they are built as one structure, they have one framework and one piece of canvas. They do however describe the relationship between two upright rectangles, one vertical and one at an angle, and in most cases, with a third form in the middle representing a result or affirmation of those two forms coming together, being bound or falling apart, etc. This repeated shape feels symbolic of something basic and poetic, so I’ve continued to explore it as a form or framework to work within.

Are your works a play on the line between illusion and object? Are they totally abstract or do they relate to the landscape or the human body?

Focusing on that in-between space, between illusion and object, is rich in its ambiguity and painting is the perfect place to explore it. It’s a way of heightening the experience of being both drawn in and pushed away.

Can you talk about your smaller monochromatic works?

Noam Rappaport, Untitled, 2015. Acrylic on wood and aluminum, 15 ¼ x 10 ¾ x 2 inches. Courtesy of Ratio 3

One of the things that interests me in the small monochromatic works is that, despite being so small, they give off the sense of being dense, like solid and heavy blocks of color. They are actually lightweight and hollow, built like models out of hobby wood and aluminum. In photographs their scale is hard to gauge, and that’s a good sign to me. My friend the artist Linda Fleming pointed out to me that in this show the smaller monochromes were like the condensed versions of their “supernova-like” counterparts in the larger works.

What about the idea of beauty? Dave Hickey muses in Invisible Dragon: Essays on Beauty about the difficulty of defining or finding beauty. For him the pursuit of beauty is like petting a tiger–coupled with an appetite for pleasant surprises.

I am always excited to see some sort of attempt revealed, with awkward or rough, as well as more refined or resolved results included. Those dispositions and all the variations between are tonal notes to play as a maker of things. I think there is beauty in including varied results where the chance for mysterious outcomes and relationships gets heightened. It seems that people often take such a binary stance on tastes and/or discontents and then rely on those stances as a view point. Attempting to avoid that thinking is compelling. I’m interested in complications that stem from less-than-welcoming aesthetics, and the challenge of bringing them together with more seductive gestures. Hopefully there is some sort of specific personal poetic that comes from that pursuit.

Noam Rappaport, Double Mend, 2015. Acrylic, canvas, cotton cord, wood, 37 ½ x 35 inches. Courtesy of Ratio 3.

—

[1] Wabi–sabi is a form of beauty based on the Zen values of the transitory nature of existence and the beauty of imperfection.

[2] Neal, Patrick. “Philosophical Paintings that Bare Their Process.” Hyperallergic.

February 5, 2016.