The David Ireland House

January 15 – March 19, 2016

500 Capp Street, San Francisco, CA 94110

Reservations required

Anglim Gilbert Gallery

DUMBBALL: David Ireland and his Circle

January 21 – February 27, 2016.

14 Geary Street, San Francisco, CA 94108

Gold hand-painted letters on the front window of a house at the corner of Capp Street and 20th in the Mission reads “Accordians – P. Greub.” Paul Greub lived in the house with his wife and other lodgers, where he also manufactured and sold accordions for more than 45 years. In 1975, Greub moved to Menlo Park and artist David Ireland bought the building to make it his home and studio. Initially, Ireland set out to dispose of everything that was left behind when the elderly Greub moved out. But Ireland soon began to see the value of these items as traces of history. It was as if the house was a giant reliquary, full of holy and sacred objects, which needed to be preserved, re-used and re-purposed. Over time, these various objects became the subject, the material, and the embodiment of Ireland’s commitment to art and everyday life. Greub had a weakness for hoarding everyday objects, even when they were completely worn. Where one might dispose of a corn broom once the whisks are depleted to the stitching, Greub would keep it but still purchase another. When the new one wore down he would buy another, and then another, but never throwing away the one before. The brooms accumulated, as did many other things.

David Ireland House (interior view); upstairs hallway with Broom Collection with Boom (1978-88), untitled chair, and wallpaper patties, 1978; photo: Henrik Kam, taken November 2015, courtesy 500 Capp Street Foundation

Soon, Greub’s brooms became the material for Broom Collection with Boom (1978-88).[1] It is comprised of 13 brooms that are attached together with a tenuous piece of baling wire that runs through holes drilled in each handle. The whole thing is precariously held almost upright by a heavier wire and an awkward slab of concrete. This collection of functional objects acts as a clock, documenting the wear of labor over time. It is on loan from SFMOMA, and is one of many pieces that will rotate on view throughout the future of the house. “It is important that the house not be shrouded in a bell jar,” Capp Street Foundation Director Carlie Wilmans explained at the press preview. Rather than a frozen homage to an artist, the house will remain a working space for exhibitions, residencies, and scholarship. The house is an art object in and of itself—a living sculpture—alive and constantly changing, transforming and becoming.

David Ireland House (exterior view), 2015; photo: Henrik Kam, courtesy 500 Capp Street Foundation

The outside of the unassuming house is a monochromatic and ghostly pale grey shell, almost bone like. Inside, the breathtaking warmth of vivid golden-colored walls in several rooms are shined to a high lacquer; bright jade green doorframes and wainscoting add playful contrast—everything preserved as Ireland had made them. Other rooms are also virtually untouched, with dingy white walls and dark grey baseboards along the untreated plank floors. The lighting is either natural, coming in from the many windows, or minimal and strange, such as bare lightbulbs on plain stands without shades, or propane gas tanks suspended from the ceiling and fashioned as a chandelier. Throughout the house there are tiny clues to Ireland’s relentless practice and dedication to quotidian experiences.

For instance, the walls at the base of two stairs are marked with small brass plaques: The Safe Gets Away for the First Time November 5, 1975 and The Safe Gets Away for the Second Time November 5, 1975. Above each one are deep gouges, damage from the time that Ireland was helping Greub move a heavy safe out of the house by rope and plank. The two men struggled; Greub was quite old at this point and couldn’t hold the rope. Ireland was unable to sustain the weight of the heavy object on the down-end and it would crash down the stairs and bang against the wall.[2] These gouges are noted with importance as one would mark the outside of a building where an historical event took place. In keeping with Ireland’s art methodology of honoring daily routine, the plaques also act as wall labels for an artwork—the act of the falling safe akin to an action painting or performance piece.

David Ireland House (interior view); downstairs dining room; photo: Henrik Kam, taken November 2015, courtesy 500 Capp Street Foundation

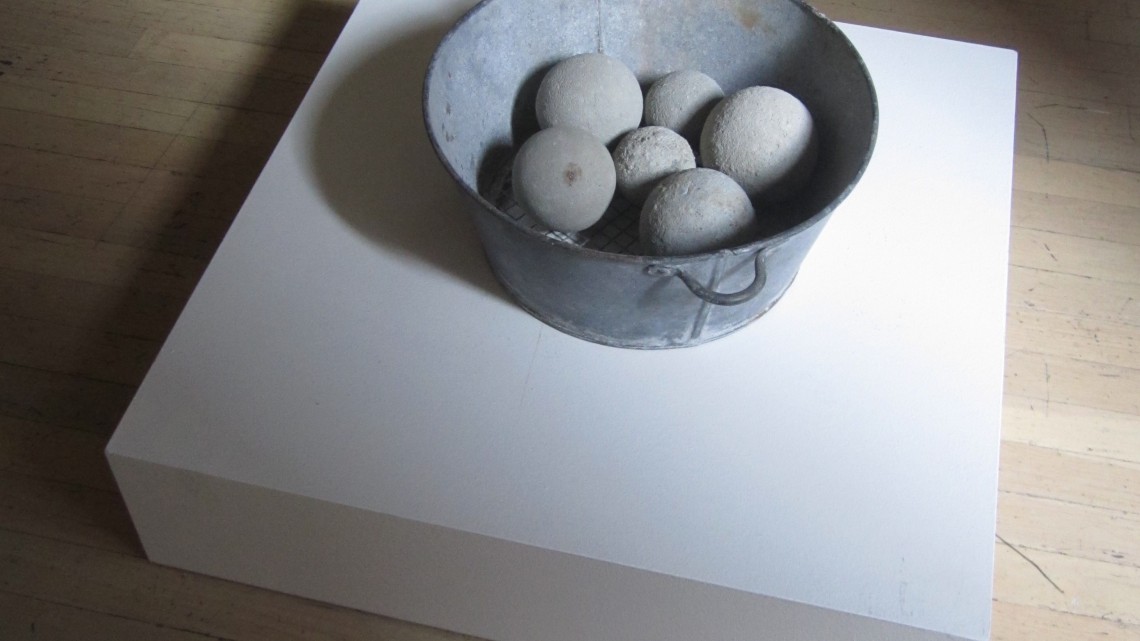

The dining room is the most abundant space in the house. In every hutch, sideboard, and down the center of the dining table are various curios and art objects: bones, animal skulls, books, buckets, photographs, maps, urns, dried bread and antique religious statues. At every turn, concrete objects are on view—from hand-made bookends of sliced concrete mounds, shards, blobs used for lamp bases. Of particular note are globs of concrete in tarnished silver desert bowls with spoons inserted in them. They are comical and at once forlorn, as if they are solidified recollections of childhood or a bygone era of soda jerks. On the dining table are a few of Ireland’s ubiquitous Dumbballs, a series that began in 1976 and continued over the course of the years, resulting in approximately 200 balls.

David Ireland House (interior view); downstairs dining room (detail); photo: LLutz, courtesy 500 Capp Street Foundation

Before elaborating on Dumbballs, it is important to understand Ireland’s choice to use concrete for making art, which seems to define him as much as the house. In 1974, while living in New York and visiting galleries, studying and examining art-making alternatives, he gravitated to concrete for its materiality; it was the perfect non-painting material with its embedded industrial connotations coupled with the alchemy of transforming from liquid to solid. The ultimate hardness of the material allowed it to remain unobstructed by the artist’s hand and was a firm ingredient in eliminating the process of “mark making” so commonly associated with painting and drawing.[3] It was at this point that Ireland began to move away from ideas of elitist or formalized and traditional art.

In comparison, the Italian Arte Povera movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s comes to mind for its minimalist aesthetic, emphasis on action, and simple, everyday objects. Artists from that movement were taking a stance against the status quo and traditional art materials in favor of found objects, and “non-fine-art” things such as brick or scraps of industrial textiles. Similarly, Ireland felt that the rules set forth by contemporary painting dogma (particularly Abstract Expressionism) created a standard by which all art was viewed and evaluated; consequently everything in comparison was “experienced as illusion.”[4] In further pursuit of the blur between (or illusion of) what is perceived to be “art,” Ireland was moving closer to the ordinary. In keeping with this, Ireland embraced Zen. In part, Zen emphasizes “suchness,” where purpose lies in accepting daily life for the way it is, without words but through actions. The Dumbballs became a practice in the ordinary materiality of concrete, but also as meditation.

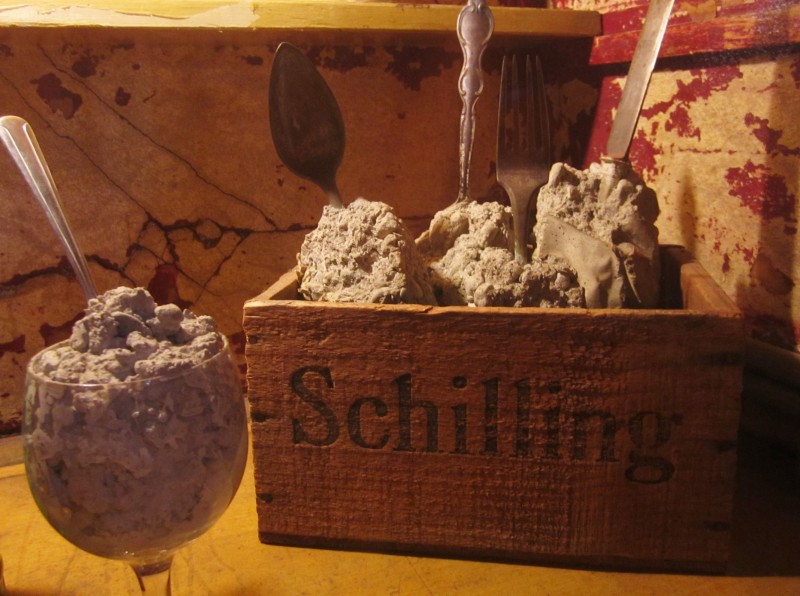

David Ireland, Dumbball Box (detail), 1983, Mixed media, 42” x 47” x 19 1/2”. courtesy Anglim Gilbert Gallery. photo: LLutz, courtesy Anglim Gilbert Gallery

To make a Dumbball, hand-sized wads of concrete are tossed back and forth in rubber-gloved hands. With each movement, the wad begins to compress. A slapping sound accompanies it as the shape is turned and passed back and forth for hours. Eventually, a symmetrical sphere is formed. This seemingly inane gesture represents the epitome of artistic process, and testament to the dedication and extreme thoughtfulness that imbued Ireland’s logos and work ethic. Though the balls are intentionally made with a particular yet highly simple formula, they are each different and subject to the outcome of the process, as opposed to the process dictating exactly how each one would come out. This playful methodology shows in Ireland’s humor when he refers to the broken or inconsistent balls as Smart Balls.[5] The process is in keeping with other minimalist notions of chance operations such as from the likes of John Cage.

David Ireland House (interior view); upstairs study showing Ireland’s desk and untitled wire piece; photo: Henrik Kam, taken November 2015, courtesy 500 Capp Street Foundation

Cage was a favorite of Ireland’s and he did several works in homage to him, including dipping the balls in ink to use them as a tool for drawing. A Variation on 79 side to side passes of a Dumbball, dedicated to the memory of John Cage 1912-1992 (1992) and two other similar works are included in a group show now on view at Anglim Gilbert Gallery titled DUMBBALL: David Ireland and his Circle. The show includes works by Ireland and his colleagues such as Ann Hamilton, Mark Thompson and those who Ireland inspired, mentored, or befriended such as Castaneda/Reiman, Rebecca Goldfarb, and Mildred Howard, to name a few. Of particular note is a piece titled 500 Capp Box—A Portfolio (1994), created with photographer Abe Frajndlich and poet John Ashbery. Similar to Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors Even (The Green Box) from 1934, which archives his piece of the same name, Ireland’s box is like a miniature version of the Capp Street house. The exhibition coincides with the opening of his restored residence, and provides an intimate look into the collaborative nature of Ireland’s way of life and with his work.

For Ireland, “context is extremely important and always to be considered by the artist and the viewer.”[6] This is not so far off from the Zen statement: “Nothing in the universe is an isolated existence having no relation to other things.”[7] In other words, everything exists because of the presence of something else near it, relating to it. One cannot separate Ireland’s cumulative and meditative practice from the artwork itself, nor can we separate Ireland’s artwork from the way he lived. At the core of his life’s work there exists a house that will go on living as he did, gaining new context as time goes by.

David Ireland House (interior view); upstairs front parlor with South China Chairs; photo: Henrik Kam, taken November 2015, courtesy 500 Capp Street Foundation

500 Capp Street is open to the public for $20 a visit. Tickets are available here

—

[1] Karen Tsujimoto, David Ireland, Jennifer R. Gross, Oakland Museum of California, Addison Gallery of American Art, Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, The Art of David Ireland: The Way Things Are, University of California Press, 2003, 152.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 156.

[4] Ibid., 158.

[5] Betty Klausner, Touching Time and Space: A Portrait of David Ireland, Spain: Charta, for San Francisco Art Institute, 2003, 16.

[6] Tsujimoto, 113.

[7] Nikkyo Niwano, trans. Buddhism for Today: A Modern Interpretation of The Threefold Lotus Sutra, Tokyo: Kōsei Publishing Co., 1976, 80.