Virginia Colwell: Our warmest and most affectionate greetings

Marso Galería

Berlín 37, Col. Juárez 06600, México, DF.

February 2016

It’s easy for us to forget in all our ever-present over-interconnectedness that even as recent as 10 years ago, much less 30 years ago, letters were the primary means of communication, especially between radical leftist movements. And that the life of those underground radicals was lonely and anxious and ambiguous, especially as they wrestled with what is a justified use of lethal or symbolic violence, and that the solidarity they sought in their struggle would only be available from other radical groups, perhaps continents away.

So, perhaps, it seems strange at first that a radical group that deployed over 125 bombs in the United States between 1974 and 1983, would always sign their correspondence with other liberation movements around the world, “…our warmest and most affectionate greetings.” This is just the first of the slippages that artist Virginia Colwell mines in her exhibition of the same name at Marso Galería in Mexico City.

Colwell’s practice is frequently inspired by an archive of documents her father, who served in the FBI, left when he passed away. Her resulting works operate like feed-back loops between the personal and political. The work presented in Our warmest and most affectionate greetings is no exception.

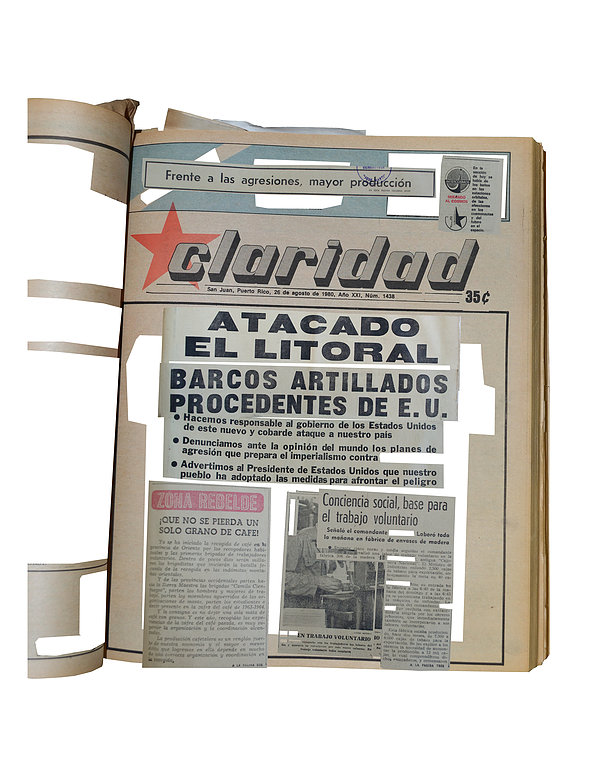

Virginia Colwell, Newspaper for a Puerto Rico Libre, 26 of August 1980, 2016.

Digital print, 92.5 cm x 71.5 cm. Courtesy of Marso Galería

The exhibition is the result of her investigation of the clandestine revolutionary organization FALN (Fuerzas Armadas para Liberación Nacional) that sought to liberate Puerto Rico from the United States. In the show’s accompanying text, Colwell speaks of her childhood memories of her English-language kindergarten class and her parents’ expatriate friends when they lived in Puerto Rico. Within the framework of the exhibition, she accepts these memories as a personalization of the embodiment of the colonialist bubble that FALN was fighting to liberate Puerto Rico from.

The works in the exhibition wander through various media: digital and hand-cut collage, video, audio, delicate graphite drawings, a series of paper small maquettes of the bomb sites, and copies of the original research documents.

The central theme is slippage; there’s the slippage between her childhood memories of the island and the political context that brought her family to Puerto Rico, the slippage of investigation as one struggles to reconstruct the past or perhaps understand the motivations of a terrorist group, and the cognitive slippage of a group of committed radicals fighting to liberate an island they had never set foot upon.

Virginia Colwell, A Net, A Bind, A Game, 2016. Tri channel digital video NTSC and bilingual audio, 13 min, 55 sec. Courtesy of Marso Galería

Her caring and delicate treatment of a little-known past seems to stem from an understanding that investigation is a construction and therefore is subjective. The process of researching to reconstruct a moment or the motivations of a group is a slippery endeavor. Each piece of evidence examined, each interview granted, amplifies the field of vision, but in the process shifts and distorts the clarity of previously arranged conclusions. Even inside an organization, the subjectivity of one fighter’s views versus another’s makes even the most clearly articulated efforts of a liberation group cloudy.

The show is anchored by A Diptych, A Chronicle, a 2-channel video installation featuring a female voice narrating the FALN’s story. The video projected on the wall is a series of seascape images, presumably shot standing on the beach in Puerto Rico. A small television on the floor plays home videos Colwell’s father took of various Caribbean islands from a sailboat. Her narrative begins generally, analyzing islands as cognitive constructs. Is the beginning of an island the peak of the mountain that rises out of the sea? Or is it the beach, the maritime travel point of entry where an island begins? Is sand not the form by which runoff and rubble of the mountain fulfills its journey to the ocean? She then relates the difficulty of distinguishing beginning, middle, and end of an island to the difficulty of parsing out FALN’s revolutionary story, returning again and again to her central question, “what justifies what?”

Virginia Colwell, The Atolls, 2016. Paper, compressed cardboard, book cloth, and photographs, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Marso Galería

The exhibition includes collages of Caribbean islands as scale models standing on saw horses, upon which Colwell has collaged images of known safe houses of the FALN in New York (the headquarters of the FALN), New Jersey, Wisconsin and Illinois. They seem to ask what is the role of geography in freedom fighting? How far can we divorce the fight from the place being liberated before the logic breaks down? Whose fight is this? And whose idea of liberty is being fought for? Is FALN’s battle for “liberation” of a distant place just a romanticized twist on colonialism colored red?

The timing of the exhibition seems prescient given the grave current state of Puerto Rico’s debt crisis and the island’s lack of rights and debt restructuring options that stem from its status as a protectorate rather than a state.

Whether the exhibition’s timing is coincidence or speaks to the protracted length of Puerto Rico’s struggle in their ambivalent relationship with the United States, it’s a reminder of the chain by which the effects of yesterday’s political scheming festers into today’s troubles, which in turn become tomorrow’s call for revolution.