The fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent famously quipped that “fashions fade, style is eternal.” This enigmatic statement does much to elucidate the powerful place that style holds in many contemporary cultures. In particular, it alerts us to the relationship that exists between notions of style and notions of history. Or, to the idea that “to have style” is to have the means of inserting oneself into history, while “to lack style” is to risk oblivion. This column, Style Wars,” suggests that the tracing of style’s fluctuating movements across varied social, political, aesthetic, and philosophical terrains is important work, and that this is particularly true within the realms of fine art, design, art history, and visual studies (as many important figures within these fields have long vied to claim and contest the ownership of this term). Style Wars aims to appreciate how thinking about style can offer opportunities to think across sets of subjectivities and cultural practices that are often disassociated or pitted against one another.

Lydia Brawner’s installment of Style Wars sets out instead to remind us that not all modes of self-styling are visual by considering how important scent is in the construction of one’s identity. Along the way, Brawner’s essay conjures the complicated way that smell wafts between the most private and most public aspects of our lives, and it sniffs out how closely the politics of smell map onto histories of bodily containment. By its end, we are haunted by the fantastic odor of the best version of ourselves.

– Nicole Archer, Column Editor

***

Chanel No. 9

With hundreds of new fragrances, how do you know which are for you? The secret: Use your style as your guide!” Like fashion, your scent should fit your mood and where you’re going,” says Sheena Chandran, Sephora’s director of fragrance merchandising, “It’s the invisible finishing touch.

– From How to Find Your Best New Scent, on harpersbazaar.com

One of my first jobs was working in the fragrance section of an East Alabama department store during the mid-nineties. At the start of a shift I would spray myself with Carolina Herrera (1988) or Trésor (1990)—thick perfumes full of big white flowers and fat peaches that even then felt slightly out-of-date and way too old for me. They made me feel like I belonged in a nice-ish department store—womanly, cheerful (words I would not generally apply to my fifteen-year-old self). Swathed in syrupy scents, I became a different, saccharine version of myself. Fake smiles came easily, customer service was a breeze; it was a game. This job was frequently an exercise in biting my tongue while older women and college students who might have more naturally worn Trésor yelled at me for offering them a sample spray of Calvin Klein’s CK One. The unisex fragrance had come out the year before, and we were pushing it hard.

We eventually had to stop offering the samples because we got so many complaints. CK One, released in 1994 and created by Alberto Morillas and Harry Fremont, is, in and of itself, actually lovely. It’s a freshly showered skin smell, citrus with a bit of musk. It’s all pleasant soap, good health, and clean living. No matter how much I enjoyed my Carolina Herrera disguise, its sweetness is borderline repulsive. CK One is not that. If anything, it was a throwback to the previous century and the first mass-produced colognes like Guerlain’s Eau de Cologne du Coq (1894) or Impériale (1853) . . . pleasant lemony smells for first thing in the morning. So what made CK One so vehemently objectionable? Why did some people consider its wafting presence to be “nasty,” or “pornographic” even?

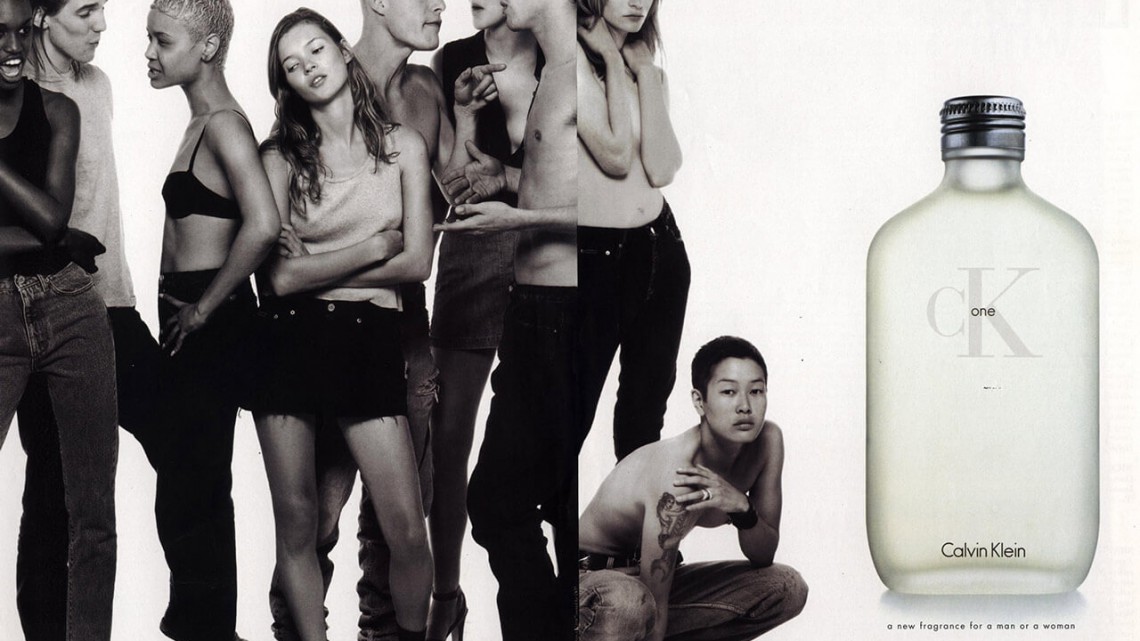

The year before the CK One release, a Steven Meisel-helmed ad campaign for the brand’s denim line featured young models being asked to undress by an off-screen male voice in what appeared to be a creepy suburban basement. The women yelling at me in the mall weren’t wrong—the ads stunk, badly. Previous Calvin Klein ad campaigns had toyed with the appropriateness of representing teenage sexuality, but these newer ads weren’t titillating—instead of young models knowingly delighted by their sexuality, the ads aped the look of ‘70s pornography and play-acted predation in a (naked) bid to drum up outrage. (As with many things designed exclusively for the reflexive pearl clutching of an older generation, they now just read as flat, or worse, boring.) Yet, for all that, no one objected to free samples of other Calvin Klein offerings like Eternity (released in 1988 and created by my beloved Sophia Grojsman, who also did Trésor and for what its worth Coty’s Ex`cla-ma`tion! (1990), which you can still buy for a couple bucks at any drugstore). There was a disconnect between the cutesy, freshly scrubbed smell of the new perfume and the department store customers’ horrified reactions to it. The commercials for CK One featured black-and-white shots of multigenerational, multiracial, gender fluid hang-outs; a pre-Foxfire Jenny Shimizu pulled at her tank top and stared into the camera, while Kate Moss cooed “A fragrance for everyone.” The angry women who campaigned against our free samples would have loved the fragrance in Estée Lauder drag—a different bottle and an innocuous femme-y name, but the (now iconic) art direction had turned CK One into something that maybe smelled dangerous, queer, and revolutionary. Even if it was just a new Impériale.

The job made me pay attention to contemporary perfumery. I still do. I frequently name-check chemist and fragrance writer Luca Turin as my favorite art critic. His recent takedown of Miu Miu (2015) on style.com/Arabia moves seamlessly from science lesson to Roland Barthes to matters of the spirit (“I cannot imagine why a woman would want to smell like her soul has been scorched . . .”) all in the space of two short paragraphs.1 It’s not just the smell that matters. It’s all of it—it’s the whole capitalist kit and caboodle of desire, fetish, salesmanship, class, aesthetics, and memory. We are encouraged through advertising copy and received wisdom to add scent to our identities, as “the invisible finishing touch” of our own style in a complex negotiation of consumerism, taste, and fantasy. After he had lost his sight, I saw my grandfather make a woman blush by telling her that he knew she had entered in the room because he had smelled her perfume. It wasn’t true of course, but the idea that it could be was so seductive. And again, the nice Christian women screaming at me about CK One weren’t wrong: everybody gets that perfumes, scents worn on the body and announcing your arrivals and absences, can be, if not pornographic, certainly sexy.

In his 1947 study of the nineteenth-century poet Charles Baudelaire, the twentieth-century existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre claims that:

The smell of the body is the body itself which we breathe in with our nose and mouth, which we suddenly possess as though it were its most secret substance and, to put the matter in a nutshell, its nature. The smell which is in me is the fusion of the body of the other person with my body . . . a vaporized body which has remained completely itself but which has become a volatile spirit.2

Charles Baudelaire, Portrait of Jeanne Duval, 1850. Courtesy of the Internet.

Byredo’s Baudelaire Eau de Parfum, released in 2009. Courtesy of the Internet.

In this intimacy of Sartre’s fusion of bodies and possession of secret substances, there is something so sensual, and on the other hand, almost frightening about it—smell crosses boundaries and crosses membranes, into our bodies through our noses and into our very memories, into the color and texture of our feelings. Commercial perfumes are also, of course, in our bodies and not just decorating it. One of the poorly guarded secrets of perfumery is that it is probably terrible for us. Molecules for families of synthetic musks, the building blocks of 20th century European commercial perfumery, have been found collecting in our fat, blood, and breast milk. They pool in especially high concentrations in Lake Michigan, slowly poisoning the fish. This somehow, shouldn’t be all that surprising. The genesis of modern perfume is violent and literally explosive. After musk deer had been hunted almost to extinction in Europe and Asia, scientist Albert Bauer discovered the first synthetic musks, known as nitro-musks, in 1888. He was looking for a better formula for more explosive dynamite: the pleasant smell was an accident.

These disincarnate bodies are volatile spirits; they do not always behave. Baudelaire himself has actually inspired a perfume, Byredo’s Baudelaire (2009), which takes its cues from the 1857 poem Parfum Exotique in Les Fleurs du Mal. Here, Baudelaire compares the smell of his longtime lover Jeanne Duval’s body to an island landscape of savory fruits and singular trees, with a welcoming port exhausted by the waves of the sea. Duval was Haitian; Baudelaire smells his fantasy of the island through her skin. The advertising copy for the perfume maintains these colonial fantasies—and at Duval’s expense. It’s pitched as a more masculine scent, or was when I went to a cosmetics counter to smell it, though, like many newer niche brands, Byredo doesn’t divide its fragrances by gender. Duval is left out of her own perfume, but I wonder now, volatile-spirit-style, what she might have enjoyed smelling like. What perfumes she might have worn on her wrists in 1857? Impériale?

Chanel N. 5 advertisement. Courtesy of the Internet.

Future and Drake, Jumpman, single cover. 2015. Courtesy of the Internet.

So what do we do with this volatile, identity-sustaining commodity that we are so frequently encouraged to wear? On Jumpman, the hit from Drake and Future’s What a Time to be Alive mixtape, which was on constant replay in my head and on every car radio for all of November in 2015, Future raps at the end, “Chanel No. 9, Chanel No. 5, well you got ‘em both.” This line always plays in my head like Future saying that he is Chanel No. 9 and Drake is Chanel No. 5. I love it. It’s perfect. In a song resplendent with luxury goods, commercial fragrance gets a shout out. But not just any: the powdery musky rose of Chanel No. 5 is probably world’s most famous fragrance . . . Chanel No. 9 is mythical. If it did exist, (and it’s not in the Osmotheque fragrance archive at Versailles, so it might never have) it would have been one of the first of Ernest Beaux’s perfumes created for Coco Chanel in the 1920s. There is rampant, rapturous speculation online about what No. 9 might have smelled like. The best sources I have found claim that it was a kind of Chanel-y dirt, masculine, and sparkling. Being Chanel No. 5 isn’t a dis per say, but it is a nod to its ubiquity. Mothers and daughters love it. It is just a little basic. But Chanel No. 9? Legendary. Singular. And what better “finishing touch,” than to be something so legendary that it doesn’t matter if it existed or not? It’s all in the imagination of the smell and the invention of its memory. Nothing else will ever smell like it. Nobody else will ever smell like you.

1) “Message in a Bottle: Luca Turin Reviews the Latest Azzedine Alaïa and Miu Miu Fragrances”

2) Satre, Jean-Paul, Baudelaire, trans. Martin Turnell (New York: New Directions, 1950) 174.