The Grace Jones Project

Museum of the African Diaspora

685 Mission St. San Francisco, CA 94105

April 27 – September 18, 2016

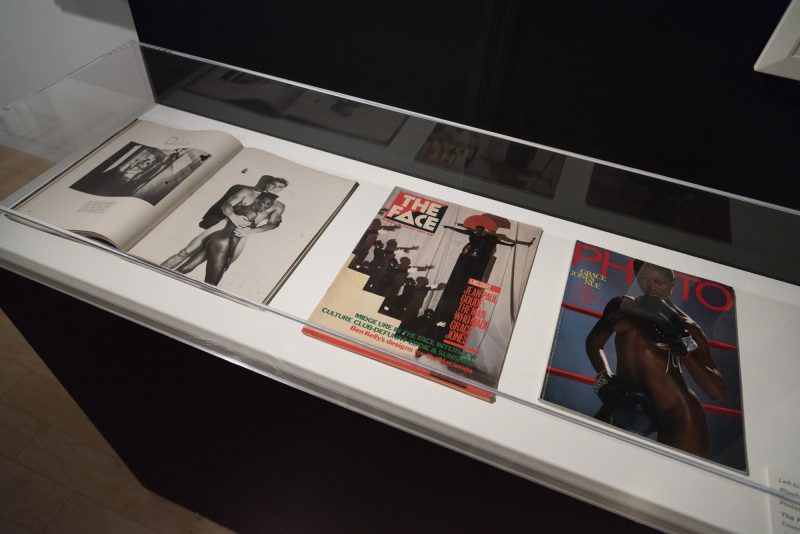

Grace Jones’s “Slave to the Rhythm,” hit the charts and MTV in 1985, and during that time she also posed nude for Helmut Newton with buff action-hero star/sensation Dolph Lundgren for Playboy magazine. The public at large was presented with one of the most intense and unapologetic images of a woman imaginable. Jones paraded her sexuality with power—her prowess put cutesier pop women performers to shame who seemed to be merely toying with audiences in comparison to Jones’s incredible contralto voice that ranged from baritone spoken word to high soprano notes. Jones stood out in her entire being as a black woman and a sexual person.

For those of us active in music and the club scenes, “Slave to the Rhythm” appealed to the working-class roots from which so many underground genres stem, including ska, punk rock and no wave. The song’s music video was directed by Jean-Paul Goude (her French white male producer and lover), and in retrospect the video is problematic; there is a tremendous amount of commentary on minstrelsy, black face, and other racist stereotypes throughout. The lyrics are like those of an activist song, calling listeners to “Sing out loud, the chain gang song,” in the second stanza; an obvious reference to slavery and work songs often sung to keep time during gruelling hard-labor. When taken in the context of the ‘80s it can also be read as an anti-capitalism song against the music industry. In addition, it can be interpreted as a metaphor for a bound commitment to music itself as life-blood and passion.

It is with the same passion and political drive that the artists in The Grace Jones Project—currently on view at the Museum of African Diaspora—have approached their work. Curated by Nicole J. Caruth, the exhibition focuses on “contemporary artists who Grace Jones has influenced and inspired, and artists who address black bodies and queer identity in ways that recall aspects of Jones’ oeuvre,” she said in an interview with Crave.[1] Calling upon references to identity and performativity that are inspired by Jones’s iconic presence, not only as a woman of color but also as a performer who epitomizes gender androgyny (as we called it in the ‘80s), the exhibition brings to light issues of corporeality and how black bodies contend with race and gender.

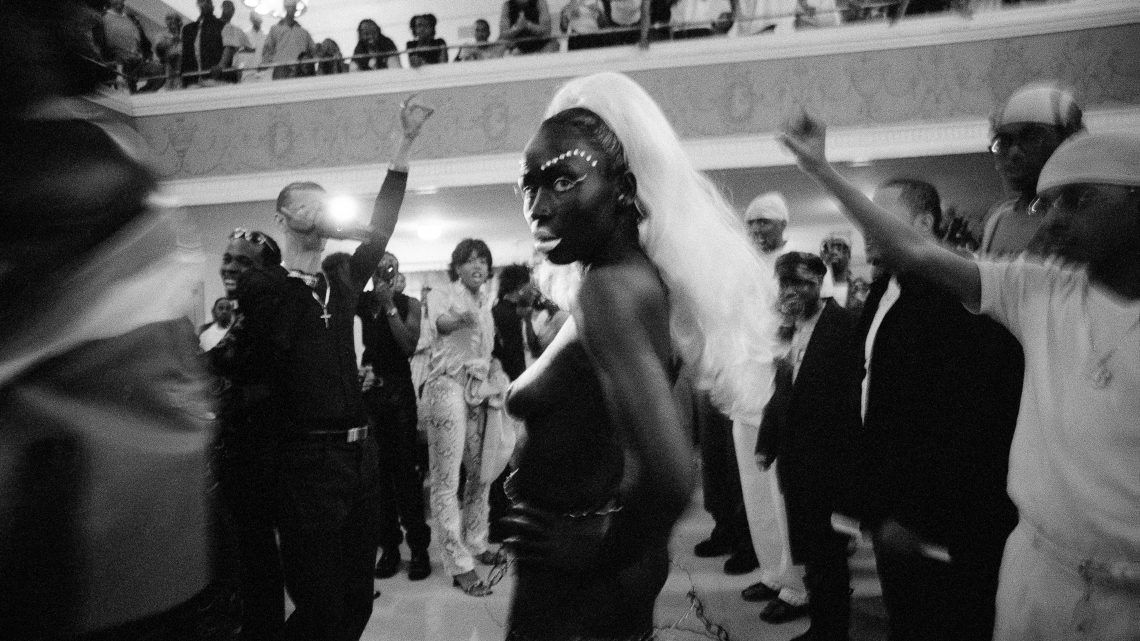

Installation view, The Grace Jones Project, Museum of the African Diaspora, April 27 – September 18, 2016.

Prior to 1985 Jones had already gained a cult following in the New York club, avant-garde music and film scenes of the 1970s due to her successful modeling career and work with Island Records and Jean-Paul Goude. Grace Jones’s touring performance A One Man Show premiered live at the Savoy in New York in 1981, featuring songs and videos. A One Man Show clearly denotes layered meanings between individual identity and gender-bending; “one man show,” in and of itself plays with the idiom for work or labor that is performed by a single-handed individual, while the use of the word “man” instead of “woman” challenges established gender binaries.

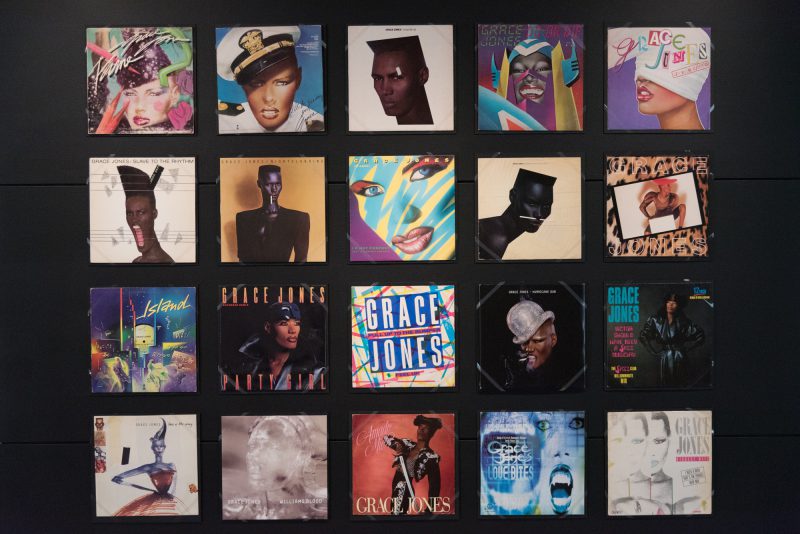

On the back wall of the museum installation several excerpts of A One Man Show along with an assortment of videos play in a loop. Nearby, a selection of record albums are formally displayed on two stationary walls painted black. After her hit “Slave to the Rhythm” in 1985, One Man Show was relaunched as State of Grace to coincide with promotion of her new material. State of Grace implies something governmental: a state all of her own, while at the same time implying that she herself is in a state of grace, as in a place of sheer poise.

Poise and images of the body are seen throughout the exhibition. Whether posing, dancing, or performing, many artists draw from sources either directly referencing or inspired by Jones, ‘80s culture, queer dance clubs, fashion, and historical black performance—all tinged with concepts of the gaze.

Mickalene Thomas, Ain’t I A Woman (Keri), 2009. DVD and framed monitor, rhinestones, acrylic and enamel on wood panel; 36 x 28 inches (painting), 36 x 58 inches (overall). Courtesy of the artist and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Mickalene Thomas’s Ain’t I A Woman (Keri) (2009) addresses issues of black female stereotypes and the labors of adornment that women undergo to maintain presentability in society, and how they are in constant competition with men in the struggle for equality, and as objects of the male gaze. The title refers to the famous speech by abolitionist Sojourner Truth: “And ar’n’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! [And here she bared her right arm to the shoulder, showing her tremendous muscular power] I have ploughed, and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ar’n’t I a woman?”[2] The title Ain’t I A Woman acts as a double-entendre in context with Jones’s title One Man Show. In addition, the Thomas piece is at the entrance of the exhibition, which clues visitors into the overarching focus on the body throughout the works, while the sequins and glittery surfaces imply a sense of kitsch that also pervades. One could even say that Jones is kitsch, and that without it she may not have been taken seriously. Sometimes humor is needed to deliver difficult topics.

Back inside the main gallery, two videos by Narcissister also use humor. Narcissister (also known as Isabelle Lumpkin) is a female-identifying performer based in Brooklyn whose work focuses on overt female sexuality. Using pop-culture references in conjunction with parody, her performances and videos pull at the exploitation of race and gender fetishes. Every Woman (2010) features a burlesque dancer wearing a brown skin-toned half mask, a huge afro and a merkin (a pubic wig). The scene is set to the Chaka Khan song of the same title, remarking on race exoticization: it is grotesque rather than sensual, which is the point. In one scene she pulls red stockings out of her vagina and then puts them on her feet, and in another scene she pulls a cheap yellow vinyl hand bag from her jumbo hair-do and jauntily slings it over her shoulder in a fashion pose straight out of a 1980s JC Penney TV commercial.

Across the way, Jacolby Satterwhite’s video En Plein Air: Music of Objective Romance: Track #1: Healing in My House (2015) also comments on eroticism. This 3D animated film offers a fantastic sci-fi environment where men and women in bondage gear perform erotic moves, while creature-like robotic tentacles swirl and grow into mechanical forms. As the scenes quickly shift like a video game, the architecture of weird tubes connect platforms that reveal the dark underbelly of a futuristic city before colliding into space. Spliced with this animated environment are filmed scenes of a young go-go dancer practicing moves on the dance floor before a big night and another man in bondage gear and cap posing in a grungy bathroom stall.

An a cappella version of a song created by Satterwhite’s mother, Patricia Satterwhite, plays intermixed with dance beats. The Healing in My House lyrics are a forlorn accompaniment to the mother-son compilation and offer homage to art-making that speaks to the notion of the insider/outsider artist. Mr. Satterwhite has gained recognition for his work at important contemporary art circles including art Basel and the Studio Museum in Harlem, while his mother who has been diagnosed with mental illness leads a secluded life at home, albeit as a prolific artist. The idea of outsider is all the more bittersweet and symbolic when taken in terms of their relationship—to be “out” in queer terms is to be open about one’s sexuality in the world—yet as the son is “out” in the world, the mother is sometimes labeled “outside” in terms of the art world.

Being out and outside is another thread that carries through the exhibition. For example Lyle Ashton Harris presents a series of portraiture that include a boxer and a transgender performer dressed as Josephine Baker; both combat sports and burlesque hover on the fringes of “decent” society, regardless of their increasingly mainstream appearances on television and in sports or contemporary dance. Gerard Gaskin’s photographs feature cos-play people from the Latex Ball or the Evisu Ball; venues that welcome the Ballroom subculture, where queer identity revels in vogue dancing and high glamor fashion, yet this still hovers in the fringes of society.

Gerard Gaskin, Tez (backstage) at the Evisu Ball, Manhattan, 2010. Archival inkjet print; 20 x 16 inches. Courtesy of the artist

This blending of both mainstream and subculture is the epitome of Grace Jones. Always pushing up against the norm, she was a constant dichotomy: both sensational and poignant, both avant-garde and popular, both female and “male.” The ‘80s saw the beginning of androgyny leaching into mainstream, and Jones was a huge part of that movement.

“Unisex” was a slogan used to describe everything from haircuts to sweatshirts to suits. Whether people identified as punkers, new wavers or metal heads, queer or straight—both men and women wore kohl eyeliner and lipstick, spiked, shaved and grew long their hair, or wore each other’s gender normative clothes; cross-dressing was a way to execute anti-establishment norms and as much as it was a symbol of gender equality, as it was a fashion statement, as it was a gender identifier. All of this is still happening now, on new terms. We still have a very long way to go before the outside can be a place where those who are out can be completely safe—where people of color can be safe, where women and trans people can be safe. Meanwhile, The Grace Jones Project reminds us that although this is the case, there is power in expression, and like Jones said, “Live to the rhythm, Love to the rhythm.”

Installation view, The Grace Jones Project, Museum of the African Diaspora, April 27 – September 18, 2016.

—

[1] Miss Rosen, “Pull Up! Curator Nicole J. Caruth Discusses The Grace Jones Project,” May 10, 2016. http://www.craveonline.com/art/982341-interview-curator-nicole-j-caruth-grace-jones-project#5GjQ0uSkUwRLDGfT.99

[2] Transcription by Frances Dana Gage, 1863. http://www.sojournertruth.org/Library/Speeches/AintIAWoman.htm