Danny Lyon: Message to the Future

Whitney Museum of American Art

99 Gansevoort Street, New York NY 10014

June 17–September 25, 2016

In the fall of 1987, Aperture magazine published a new issue entitled Witness to Crisis. Featured artists included Sebastião Salgado, Susan Meiselas, and David Goldblatt. In her discussion of the latter photographer’s series on South Africa, Nadine Gordimer writes, “Goldblatt’s photographs, in their beauty and honesty, offer the very reverse of the easy panacea of ‘understanding.’ They cause us to face the ultimate implications of what we understand very well.”[1]

Without eliding the nuances of their respective projects, I find this to be a similarly apt description of the series of photographs included in Danny Lyon’s most recent retrospective at the Whitney, Message to the Future. While the retrospective naturally encompasses a wider range of Lyon’s work than does Aperture of Goldblatt’s, the dominant series are contemporaneous, dating to the 1960s and ‘70s. Lyon’s photographs—because of their rigorous compositional structures and suggestions of genuine intimacy between subject and photographer—rise above the exhibition’s thematic groupings, which tend to reduce the series to mere documents rather than confrontational messages, as the show’s title would imply.

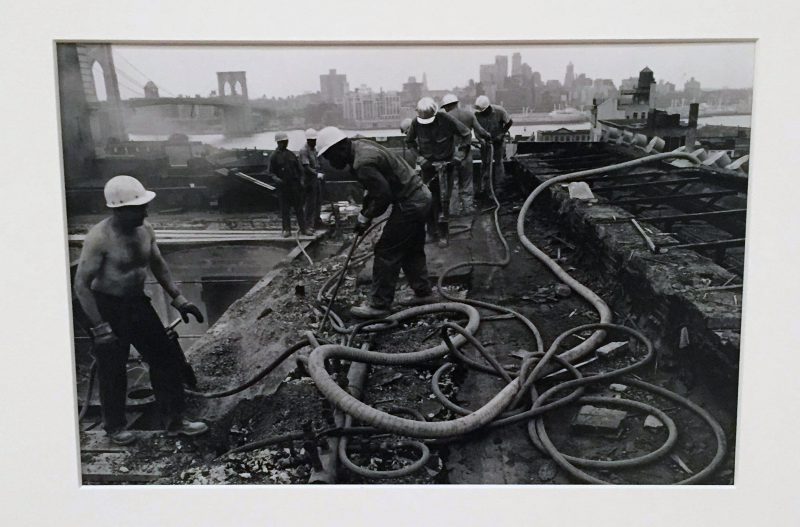

Danny Lyon, Roof, 80 Beekman Street, New York, 1967. Gelatin silver print, 20.6 x 30.7 cm (8 1/18 x 12 1/8 in.) Collection of Melissa Schiff Soros and Robert Soros

Each of Lyon’s series is specific to a certain context, as several projects were funded by the government; his series depicting the destruction of lower Manhattan to make way for the World Trade Center, for example, was funded by the New York State Council on the Arts. Formally complex and abstract from afar, these photographs unfold upon approach into more seemingly journalistic shots. Roof, 80 Beekman Street, New York (1967) depicts the primary actors in the trajectory of de- to re-construction. The workers’ hoses and power supply cords lie tangled on the ground, weaving through the rubble on the roof and encircling the human bodies like snakes. It’s a busy scene, and from afar the humans appear to be part of the exposed building’s infrastructure.

In the exhibition’s wall text, Lyon writes about these workers; “my respect for them grew tremendously. They do a difficult and dangerous job very well and it’s a mistake to think that they feel anything but pride for their work.” In light of Lyon’s stated mission to give meaning to the demise of this part of the city, this explicit relationship of respect for (and, undoubtedly, trust of) the workers responsible for that demise highlights an important tension in the series. As photographer of the destruction, Lyon could easily have settled into the position of removed documentarian. Yet framing the implications is again more important than passively understanding; 100 Gold Street, New York (1967) represents the cyclical nature of destruction. From the inside of a half-destroyed building, Lyon captures the arm of an excavator as its claw reaches up to tear apart the jagged roof. Framed as it is by both the building’s gaping hole and the high-rise buildings beyond, the excavator is caught between phases of construction—the photographer stands in the past, in the shadows of the building that once stood complete, while in the distance stands the implied future, a skyline crowded with pillars of urban development. The excavator becomes both actor and instrument, referencing also the unit of photographer and camera who together initiate this transition.

Danny Lyon, Ruins of 100 Gold Street, New York, 1967. Gelatin silver print, 23.6 x 23.4 cm (9 5/16 x 10 7/16 in.) Collection of Melissa Schiff Soros and Robert Soros

Though there is a future to these environs, Lyon’s series has a pessimistic bent. Ruins of 100 Gold Street (1967), a portrait of felled columns strangely reminiscent of Roman ruins, represents the consequence of that claw’s power. These are the phallic remains of some former ruler of lower Manhattan, recently deposed to make way for that next infamous symbol of American prowess. Tribune Building, Northeast Corner, Spruce and Printer’s Square, New York (1966) is another picture of cyclical despair: still clinging to the peeling wallpaper of snowflakes on a drab green ground, a horizontal poster of an idealized, hyper-saturated sunset and silhouetted skyline warns ominously that every aspiration towards an image must fall short. Below the poster, an exposed I-beam and heap of broken bricks drag the eye downwards towards the rubble that this building has become.

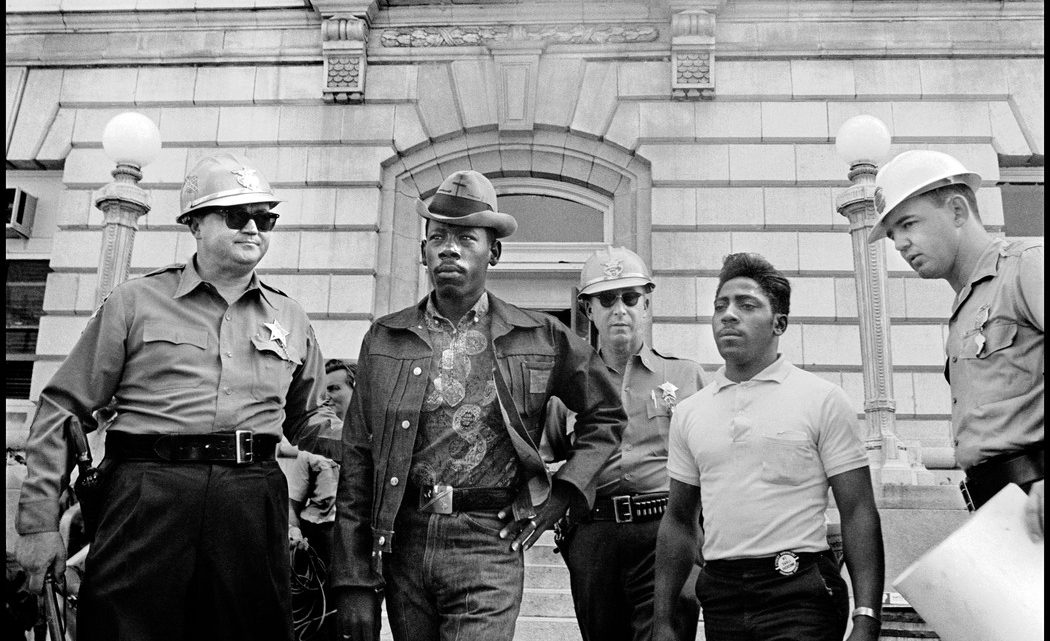

Ultimately, in order to do more than help a viewer or photographer “understand” a situation, a photograph must also perform some sort of action itself. In Lyon’s Civil Rights Movement series, shot for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), several photographs not only represent but also enact protest. Sheriff Jim Clark Arresting Demonstrators, Selma, Alabama, October 7 (1963) would, from its title, seem to submit to the power of police authority by representing their dominance. Yet the more compelling expression in the photograph is not the smugness of the white officer but rather the pride of the arrested men’s faces. Shot from lightly below eye level, the taller man’s strong gaze out towards the left side of the frame is strengthened by the suggestion of a furrowed brow beneath his hat. His attire and pose, with one arm on his hip, help him read as some kind of savior. By representing this event as one of defiance rather than submission, Lyon creates an object of protest.

Stokely Carmichael, Confrontation with National Guard, Cambridge, Maryland, 1964. Gelatin silver print. Image 16.5 x 22.2 cm (6 1/2 x 8 3/4 in.); sheet 20.3 x 25.4 cm (8 x 10 in.) Collection of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Again in Stokely Carmichael, Confrontation with National Guard, Cambridge, Maryland (1964), the compositional structure illuminates the power dynamics of the situation: the long nose of a rifle is a literal slash dividing the image. On the left, a black man in a white shirt looks out with fearful or skeptical eyes to his left. Next to him, another man stands shielding his eyes from the bright light illuminating this nighttime scene. His shirt is wet with what could be blood, sweat, or water. On the right half of the image, the National Guard officer who holds the rifle stands with his back to the camera. His helmet and shirt patches represent his authority. In this literal opposition, the sense of foreboding is palpable and Lyon’s photographic structure elegantly articulates the stakes of the protest.

In another project that was perhaps no less dangerous, Danny Lyon turned to the incarceration system and imbedded himself in a Texas prison, where he took the time to build trust with inmates in order to first understand, then convey and analyze their situations. Twenty-five years, Lonnie B. Bell, Texas, September 9 (1968) is one of the most powerful images in the series. Though it does not depict a human body, it uses an object to speak to that body’s internal distress. A calendar card pinned to the wall is marked by Xs for days past and Os for (presumably) days remaining. The logic of this system is softened by the handwriting of its owner, Lonnie, whose signature graces the top of the card. The “i” is dotted with a small open circle. These flourishes in her handwriting suggest an unbroken pride or sense of self. But the calendar is crookedly pinned to the white brick wall of her cell, another grid system that must confine her. Lonnie is somewhere in those marks of time passing, the sole comfort that one of these systems will eventually end with her release.

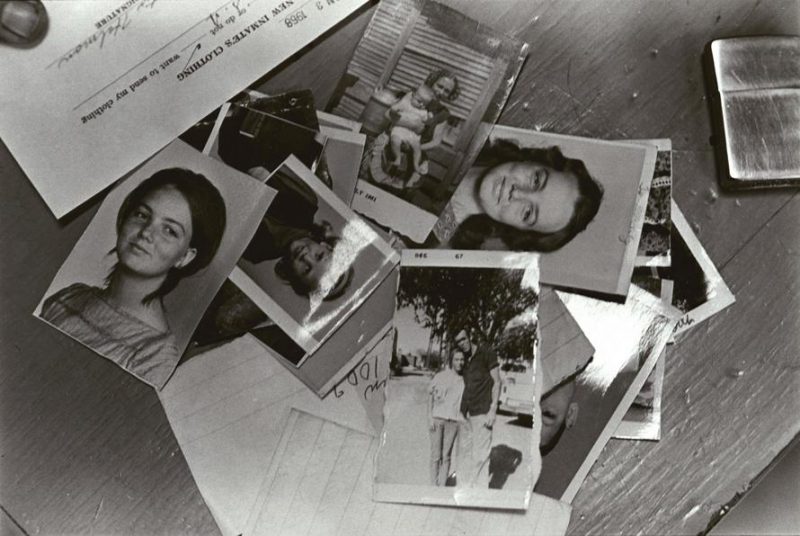

Danny Lyon, Contents of Arriving Prisoner’s Wallet, Diagnostic Unit, The Walls, Huntsville, Texas, 1968. Gelatin silver print. Image 24.3 x 17.5 cm (9 9/16 x 6 3/4 in.); sheet 25.4 x 20.3 cm (10 x 8 in.) Collection of the artist

Contents of Arriving Prisoner’s Wallet, Diagnostic Unit, The Walls, Texas (1968) depicts more personal affects: scattered on a table are several photographs and some scraps of lined paper, one visibly marked by handwriting. A young girl appears in several of the photographs throughout different ages, including one in which a taller man of a similar age leans over to reach his arm around her hip and another where a woman (the same or perhaps another) cradles a baby. In the top left of the picture is the edge of an institutional-looking form and, almost disappearing into the corner, someone’s thumb. Whose? Is it that of the prisoner who must relinquish these artifacts of a now unattainable life, or that of the officer into whose hands these photographs may now pass, their intimacy soiled by his hands? The thumb indexes this human exchange of authority, and of one life for another. A viewer may understand in theory the operations of the incarceration system, but these photographs embody a far more complex system of psychological and interpersonal relations.

Danny Lyon, Cell-Block Table, The Walls, Texas, 1967 Gelatin silver print Image 22.1 x 33 cm (8 3/4 x 13 in.); sheet 27.9 x 35.6 cm (11 x 14 in.) Collection of the artist

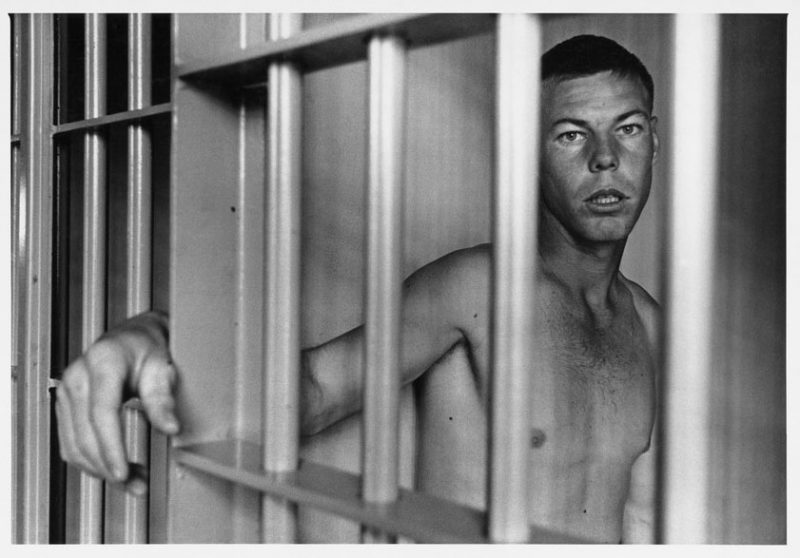

Of course, especially with the prison series, one cannot ignore the intrusion that is Lyon. When, in Cell-Block Table, The Walls, Texas (1967), the photographer looks down from above at two men playing dominoes, it is easy to believe that he is literally too far from the prisoners to understand the stakes of their game. In Charlie Lowe, Ellis Unit, Texas (1968), this division is far clearer; Lowe’s arm is foreshortened as his hand reaches for Lyon through the bars of his cell. Naked torso, slack jaw, and vacant face—he is devoid of agency. Yet even if Lyon never completely overcomes his position as outsider, there is something to this careful balance that is more real and harrowing than both removed documentation and complete entrenchment. The Aperture issue, Witness to Crisis, was prefaced by the following statement: “The journalists and photojournalists who are messengers of these grim truths uphold two prevalent motives: the belief that the photograph can affect the course of history, and the less ambitious response that it is our duty simply to record. Both emerge from the conviction that tragedy should not pass unwitnessed by those cushioned and secure, living in relative safety.”[2] More than a witness, Danny Lyon’s images uphold the conviction that “understanding” is not only insufficient, but also forever incomplete. To become intimate with the nuances of society’s ills and to reactivate those conflicts pictorially is a far more difficult task.

—

[1] Goldblatt, David, and Gordimer Nadine. “David Goldblatt: Home Land.” Aperture, no. 108 (1987): 42-69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24471948.

[2] “Witness to Crisis.” Aperture, no. 108 (1987): 1. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24471945

Danny Lyon, Charlie Lowe, Ellis Unit, Texas, 1968. Gelatin silver print. Image 16.2 x 23.8 cm (6 3/8 x 9 3/8 in.); sheet 20.3 x 25.4 cm (8 x 10 in.) Collection of the artist