Taipei Biennial

Taipei Fine Arts Museum

No. 181, Zhong Shan N. Road, Sec. 3,

Taipei 10461, Taiwan

September 10, 2016 – February 5, 2017

You could be forgiven for missing the connection between a gray men’s suit—the image of the Taipei Biennial used in publicity campaigns—and its curatorial premise. The suit is from Jean-Luc Moulène‘s 39 Strike Objects, a publication with photographs and brief descriptions of altered products made by French factory workers while on strikes between the 1970s and 1990s. What appears uniform and unexceptional is in fact the evidence of a movement for worker’s rights. 39 Strike Objects, which visitors can take a free copy of, is displayed in the stacked cardboard boxes in which the publisher presumably shipped them to the museum—a nod to the connection between the publication itself, the space of the gallery, and the labor behind the production of this artwork and the Biennial.

The suit is also a fitting image for a Biennial that might like to get political but stays inoffensive. As the title would suggest (“Gestures and Archives of the Present, Genealogies of the Future”) it’s grounded in material culture: geographical place, physical objects, and artistic and literary works are revisited as documents of social history. But while centering material culture and the archive can be a powerful tool in centering popular voices—as in Moulène’s piece, which draws attention to workers and rights movements all too often invisibilized in media and history—the approach of the show as a whole remains mild-mannered. It’s not a bad show—there are a number of individual works that are successful—but as a whole, it’s not a thorn in anyone’s side. This Biennial remains not so much critique as remark.

Chen Chieh-Jen, Wind Songs, 2015. Single channel video installation, blue-ray disc, b+w, sound in selected portions, 23 min 17 sec. Courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

A case in point is Realm of Reverberations (2014), Chen Chieh-Jen’s engagement across media with the ongoing struggle to preserve the Losheng Sanatorium, an area in New Taipei City that was used to forcibly confine people with Hansen’s Disease (leprosy). Despite protests from long-term residents, the area is under threat of being cleared to build a transportation center. Chieh-Jen presents a four-channel video with narratives relating to the history of the Losheng Sanatorium from characters including a nurse, an elderly resident, and a young activist. The making of this film, and its digestion as an art object, propels the next work in the series, Wind Songs (2015), which documents residents watching Realm of Reverberations while it is being screened at the Losheng Sanatorium. This half-smart half-annoying reflexivity continues in the form of a performance-lecture referencing the site of the lecture, etc.

This piece, at the beginning of the show, and occupying a large enough physical space for one of the best-known contemporary Taiwanese artists, sets the tone for a number of works that incorporate re-performance and its various offshoots into the work. In Prophet, Su Yu Hsien invites the original actors in a seminal Taiwanese modernist play from 1965 (the director altered it into more conservative form) to perform it as originally intended. In One. Two. Three (2015), Vincent Meessen records a contemporary re-staging by Congolese Situationist Joseph M’Belolo of the protest song he wrote that was discovered in the archive of a Belgian situationist. Performed in Club One Two Three, which was itself an important site for the development of a Congolese modernity, M’Belolo and other musicians play in and on the architecture itself—picking chords as they pace the hallways, drumming against the floor.

Vincent Meessen, One.Two.Three, 2015, three channel digital video installation (looped), surround sound, 35 min. Courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

Among Taiwanese artists, the net is cast widely—that is, vaguely—on issues of social and economic inequality. In Collectivism (2016), Eric Chen and Rain Wu reference recent social movements, such as the Sunflower Movement, with an outdoor installation of 700 bulletproof shields built around a garden. I-Hsuen Chen photographs the nest-like enclaves among mounds of trash where people make homes under highway overpasses, then pairs these images with real estate advertising copy (propping the photos up on the floor does nothing for the work, though). In Daily Life Portrait, 2016, Yi-Chih Lai photographs residents’ houses against the backdrop of the petrochemical zone in Yunlin, Taiwan. Matched with audio recordings of interviews with residents, the project also includes flowerpots made with incinerator slag. Available for purchase, the pots are a way of re-introducing waste into the market.

I – Hsuen Chen, Still Life Analysis II, The Island, 2015 -2016. Archival inkjet prints, framed photos 4: 82 x 102 cm/ 3: 61 x 92 cm, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

Apart from several works that reference the Japanese colonial period, most of these issues are contemporary and deal with economic inequality: there’s nothing on Indigenous rights, queer and trans rights, gender equity, abuse of domestic workers, etc. There’s a conspicuous absence of work dealing with the White Terror, as well as Taiwan’s relationship to China (and although Chinese artists do show frequently at museums in Taiwan, there are none in the Biennial). It’s hard not to see the connection between these absences and Taipei Fine Arts Museum’s own funding bodies. The lack of engagement with Taipei Fine Arts Museum is particularly poignant given curator Corinne Diserens’s introductory statement emphasizing bureaucracy and the institution: apparently, it doesn’t extend to the actual site of the Biennial.

One work that critiques the museum, if not this one, is Ȃngela Ferreira’s A Tendency to Forget (2015), which engages the legacy of anthropology’s service in oppressive political regimes in Mozambique, where Ferreira was born. Photographs of the National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon are spaced around gallery walls, showing the building from every angle, as though the viewer were circumambulating it, trying to find a way in. In the center of the gallery space, a teal spiral staircase leads up to a little video loft shaped like the museum façade, 10 feet above the ground.

Ȃngela Ferreira, A Tendency to Forget, 2015. MDF, pine beams, iron, LCD, 460 x 565 x 415 cm. 7 inkjet prints, 70 x 100 cm each. Video, 16:9, color, sound, 19 min 15 sec, loop. Courtesy Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

Initially I had my doubts about what just seemed like a glorified video screening area. I watched as a previous viewer—the structure can only hold three people at a time—descended the stairs. Each one bent outwards under her weight. Is this spiral staircase supposed to feel like it’s about to break? I wondered. No napping in this video lounge. I really was expecting the whole structure to fall over at some point, and this precarity, whether intentional or not, is what ultimately makes the work.

The video pairs journal entries from Margot Dias, an anthropologist who did fieldwork among the Makonde, who wrote with a sort of quotidian, ‘deary diary’ racism about, for example, the need to differentiate between educated and uneducated blacks, and the value of the educated blacks in controlling the populace. This treehouse–like structure that straddles the gallery mimics the form of the Museum of Ethnology. Its architecture carries all the authority of the state: it has dull, clean, modernist lines; nothing decorative or frivolous. If this is the colonial project, it is anything but stable: this tenuous architecture, in which the viewer must sit, could collapse at any moment.

The research-based works in the show hold up well, but where the Biennial is weakest is how painting is presented. Apart from the young painter Yi-Wei Lin, whose gorgeous acrylic and lacquer canvases emanate a particularly Taiwanese color palette, of potted plants in styrofoam boxes, faded turquoise window frames, and terazzo floors.These are paintings that are interesting not as things to look at but as social facts. They’re presented as objects relevant only in retrospect, as traces of the historical arc they occupy, with a disregard for the apparently outdated criteria of composition, color, and line—let alone the artist’s hand.

Yi-Wei Lin, Night Run Series – Flower Season of Palm, 2016. Acrylic, raw lacquer, canvas, 89 x 64 cm. Courtesy Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

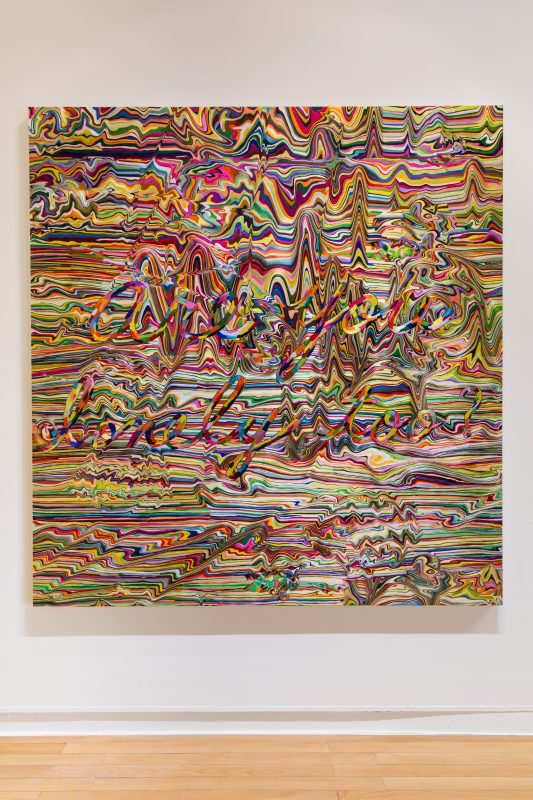

Then again, the rest of the paintings are interesting enough if you know to close your eyes to the canvas and only open them to the wall text. Kyungah Ham employs North Korean textile workers in embroidering large square canvases in a spit-up of psychedelic color with phrases mined from the internet. That Ham, who is South Korean, must go through a middleman to have them produced, and that some canvases are lost in transit, is a conceptually sound framework for an art piece (in a Santiago Sierra-style “let me expose the exploitation inherent in producing art objects by engaging in that exploitation myself” move). The claim that requesting phrases like “are you lonely too” is introducing Internet culture to North Koreans, however, is ridiculous. Kyungah Ham’s work is paired with Pen Varlen, one of several dead painters in the Biennial ‘overlooked’ by art history and whose work is similarly interesting as artifacts of material culture alone. A Korean who spent most of his life in the Soviet Union, Varlen spent 15 months in North Korea to re-establish the Pyongyang Arts Academy. It’s true that his biography is compelling, but this does not change the fact that his work, displayed here, is your average socialist realism. I think it’s possible to unite the visual—an element of painting that I perhaps naively still value—with the conceptual, without sacrificing one to the other, but not in the way that painting is curated in this Biennial.

Kyungah Ham, Whisper, Needle Country/SMS Series in Camouflage/Are you lonely, too? BC01-001-01, 2014 – 2015. North Korean Hand embroidery, silk threads on cotton, middle man, anxiety, censorship, ideology, wooden frame, approx. 1000 hrs / 1 person, 205 x 194 cm. Courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

It’s on these grounds that one work in the Biennial stands out: Park Chan-Kyong’s Citizens Forest (2016), a quiet 3-channel film in black and white that references the work of Korean artist Oh Yoon and Korean poet Kim Soo-Young. In recurring settings distributed through a forest, groups of figures enact obscure rituals with the simplest and most poetic props—masks made of baskets with holes cut for the eyes, dollar-store ghoul masks paired with hanbok, and a small boat burning as it floats downstream. A woman in white, wearing one of those shiny black visors, shines a camping flashlight in a slow arc; a series of processions of men in military jackets and bare legs moves through the woods. These beings are rarely still, and though always in motion, they never move fast, giving the scene a ghostly quality.

When all three screens sync up, we’re in a panorama of forest. In the manner of a scroll painting or Brueghel the Elder, everyone is going about their daily affairs inward-turned; only here the characters are, for example, a headless man in white stepping into the undergrowth with a hoe. It’s more Francesca Woodman than anyone else. Everything is so slowed-down as to be on the point of disappearing, which, in the end, it does, as all three screens blink into a starry sky with props from the film spinning in place: a toothbrush lashed to a laser, a plastic headband, a crushed soda-can.

So what did this film do that most other work in the Biennial did not?

With the rise of research-based practices, in which artists start from a historical event or social issue and distill it into photography, text publication, or video (and it usually is one these three), it’s worth asking, but perhaps not answering, what it is that an art object can do, or what can happen in art as a discipline, that cannot happen anywhere else.

By this I mean: I do not think that watering down some other discipline and presenting it in the space of a gallery is a sustainable way to incorporate research into practice. When this happens, the artist has merely to find an interesting premise, and the work is done before it is even begun. There is a certain formula being followed: locate some unresolved historical strand, or song, or commodity, or painting, and trace it as it makes its way through culture and archive. Perhaps find a way to re-stage the subject; perhaps lay out some “artifacts” in a glass-covered table; then document this trajectory through one glossy medium or another. This formula can be effective, as many of the works that subscribe to it in this biennial and elsewhere are. But it begins to feel like only the topic changes, while the method of approach remains the same.

Is the artist just an amateur historian with a camera and a nose for what’s weird?

Or: What can the artist add or make? What texture is the act of their noticing?

Never, for example, has one of those reflective broad-brim black visors been rendered so lyrically as it is in Citizens Forest. This film succeeds so thoroughly because it unlocks the peculiarity, the threat, the beauty latent in everyday objects, and ties these to a larger cultural text—all through the artist’s own particular aesthetic mark.