Vito Acconci shouldn’t need any introduction. His body of work is so extensive and influence so widespread it renders recapitulation redundant. That said, it can be argued that a bevy of current practitioners who weren’t born yet when Acconci was editing 0 to 9 with Bernadette Mayer and stalking strangers through the streets of Manhattan in Following Piece (1969) owe at least some of their notoriety and success to a pronounced borrowing from his oeuvre. Be that as it may, Acconci doesn’t seem too concerned about that at all and he, and the Acconci Studio, remain incredibly active and engaged. On the night we spoke at the studio in DUMBO in Brooklyn, a Merzbow show at St. Vitus in Greenpoint was marked on his calendar. As he graciously left for the deli to get some coffee before we started, I told him I wanted mine with cream and sugar. “I stopped putting sugar in coffee a while back when someone told me there’s as much in a New York-style deli cup as there is in a cannoli. I’d rather just eat a cannoli,” he said. Luckily I’d brought a couple of Toblerone bars, which we made short work of during the next hour and a half.

Starting at a point roughly in the middle of the last forty-odd years, let’s talk about Maze Table at the Wadsworth Athenaeum in 1985. It looks like it had a lot of sharp edges. When you first started doing a cross between furniture and architecture did you think people might wonder if you were against comfort?

No, I don’t think so. I don’t think I can answer that I had anything against comfort but I was thinking more about an idea of sitting, an idea of chair. I was thinking about how people use this in the sense that they entered at any of the four corners and the only way they could get to the middle was to go from one table to another table to another. I thought of, if there were people sitting at this table the person entering now can interfere with the people sitting there, but I certainly wasn’t against comfort. Probably twenty or more years later I would at least give some thought to comfort, but at that time I was much more involved with chair as an idea and if it was necessary, if someone wanted to go to a chair, with the thought that they don’t know when they want to get up, maybe they want to stay there for a while. Maybe they would start to think, “This is so comfortable I could die here.”

Maze Table, 1985. Courtesy of the artist.

But from around the same time, though, Sleeping Dog Couch looks comfortable for lounging.

Exactly the same time, but it probably didn’t come from comfort, it came from the idea of a dog, a dog is soft, everything was soft, it was a rug on the outside, leather, leather on some pillowed-like stuff. But I’m sure at that time it came from if a dog is used as a couch, unless it’s a dead dog, it’s a good couch.

Prior to all that you did a lot of performances that often involved situations in which you were making yourself suffer, other people suffer, or at least uncomfortable. When you started doing things like Maze Table, in the mid-1980s, was part of the impetus that you had suffered for your art, in a manner of speaking, and now you were going to make other people suffer too?

I never thought that. I did think that now that I was making stuff for other people I didn’t want to make other people necessarily uncomfortable. But with Maze Table, and this is something that isn’t really known, it was done for the Athenaeum’s Lions Gallery of the Senses, for the visually impaired. So I wanted to make something that sighted people would not have a privileged view of, therefore I wanted to make it transparent, with glass. The blind aspect was really important, that was its starting point. It was amazing seeing blind people use it because they quickly realized it was glass, they very quickly went through it with a cane, and they did it faster than any sighted person could. They didn’t need “sight.” It wasn’t an encumbrance to them, it was an aid. A maze might be uncomfortable for a sighted person but really comfortable for a blind person.

Who are used to the whole world being a maze. On the subject of comfort again, and this is sort of a “lifestyle” question, do you have sofas at home, do you have soft, “normal” furniture?

We live in a very small apartment, a tiny apartment, in Chinatown, and there’s a sofa which we usually use to put stuff on. If we want to sit or be comfortable we lie on the bed, and if I’m sitting I’d rather sit on a stool or a chair, because I’m going through newspapers, or doing work. Basically the sofa was bought because it pulls out as a bed and it’s not easy for people to stay over, but it can be done.

So you’re not collecting mid-century Modernist furniture?

I love the idea of furniture, but not as fine design exactly. I like design that has two or three directions or two or three goals, more than one thing at a time, that’s very important to me.

What’s an example? Like, a sectional couch?

No, more if there’s a place where two people are sitting next to each other, but the sofa-like thing is so shaped that somebody might be able to sit behind someone, or to the side. I like thickening the plot. I don’t like the idea of one purpose and at the same time I love architecture and design I hate it because it makes people subservient to it. I think that can’t possibly change until people by using something can change. Whatever they’re sitting in, whatever they’re living in. Can that happen? There are ways. We’ve done it with something that has a hinge, so it can be up, or down, but that’s not real freedom. Suppose someone wants it to move another way? That’s an obsession.

One of the early Acconci Studio projects was Personal Island, right? Like, every man is an island?

I don’t know if it came from that. It came from the fact that I’d been asked to do something at this little park in Holland, the occasion was some flower show, with a very small budget, maybe two thousand dollars. The interesting thing about most cities in Holland is that where there’s land there’s probably water. So let’s do something with rowboats, they’re relatively cheap. You drive a rowboat into the ground so it becomes almost a park bench. And there’s another rowboat facing it, and it’s attached to a circle of grass, so now if you go into that rowboat you can take that out into the water and have your own island. It was a way to do something relatively cheap but also something where, well by that time, I was convinced that people had to do things for themselves.

Personal Island, Floriade, Zoetemeer (temporary), 1992. Acconci Studio (V.A., Luis Vera, Jenny Schrider).

A noble impulse, though I doubt people are actually going to start doing things for themselves. Possibly that’s overly utopian.

They might use their iPhones.

There are a lot of video games to play.

They might have a thousand and seventy friends on Facebook. It’s an interesting thing, you can be acquaintances but maybe never friends. Facebook friends. You can skip. It’s a great thing about the computer age, you don’t have to read anymore. There’s a lot of surface, and surface isn’t bad. If you go into the surface you can go much more into things in depth. But if you want to read The Brothers Karamazov it’s going to take a while.

You’re going to have to get on your personal island for that. What’s neat about Personal Island is that it’s small-scale and turns a lowly rowboat into an island, which is a thing rich people buy. But this is a different contrasting kind of island. So when was the transition from just you to Acconci Studio?

Well, 1980 was kind of the big change with some of the first pieces, well, pieces were starting to be more publically used, before Acconci Studio started in 1988. There were installations throughout the 1970s and people were part of something but in the 1980s I wanted things to be participatory, though I don’t know if that’s a good enough word. With Instant House (1980) somebody could come and think there are four American flags on the floor, there’s a swing in the middle, the person decides to use the swing, and the walls come up and the person becomes implicated or starts something that wouldn’t have happened if that person didn’t do anything. A lot of people had no idea what the piece was about. A lot of times circumstance makes a big difference. It was first done at The Kitchen, and some people said to me, “I didn’t understand that piece of yours with the American flags on the floor.” Because they hadn’t gotten in the swing so the walls didn’t come up. But a few months later it was in the Venice Biennale and there was a corridor with rooms on either side and a room at the end, and Instant House was at the end. So as people went down the corridor they inevitably saw it being used and that changed it completely so they knew it was supposed to be used.

Instant House, 1980. Courtesy of the artist.

As opposed to walking into an empty gallery and seeing it inert. Around the same time, Park up a Building, and House up a Building, they have insouciance that could be interpreted as thumbing your nose at the audience.

But why? You’re giving people a place to go they would never have had before. During that show House up a Building was used by people, as a kind of house. How many times do you get to climb the outside of a building?

Being critical, one could say they were parasitic to their host buildings.

Definitely a parasite. The house took the electricity from the museum, it took water from the museum. You could wash, people stayed there. They usually stayed there part of the day, they didn’t leave it a mess.

Around the same time Garbage City, near Tel Aviv, 1999, though it was never completed seems extremely prescient since now recycling is such an obsession. It was ahead of its time, using methane gas to power things, actually incorporating “reuse” instead of empty rhetoric.

Originally a number of people were invited to make proposals for this garbage dump that was no longer being used. It had been there for almost fifty years, since Israel began actually, and because of the accumulation of garbage it was drawing multitudes of birds and since it was very close to the Tel Aviv airport they were worried birds would cause airplane accidents. They stopped using it, and asked for suggestions. So I don’t know if I would have thought of it myself. But once it was presented, we try to take these things seriously. We worked with an environmental consultant from Arup and asked, what are some of things we should know? And he said the most important thing is the methane gas, it’s always going to change because the methane gas is going to be constantly released. He also estimated that there was enough methane gas at the dump to generate electricity for probably the next fifty to seventy-five years. I really loved that project, and the guy who asked us, I think he kind of loved it too. But eventually he had a landscape architect do it. I admit, I felt a little piqued. It wasn’t the worst landscape architect, but well, we had a grazing field for cows.

You’re saying that as if it was of overreaching, but now you have urban rooftop farms and these kinds of ecologically progressive notions are the currency of the day. They might have seemed very farfetched then but they’re not ten or twelve years later. On a related subject, you once said, “I’m interested in landscape not just as something to look at, but something to touch.”

Can you go through the landscape, can you go under, can you transfer the landscape to somewhere else, and can you treat the landscape as if it’s water? You can move water, can you move landscape? I don’t know enough about this stuff, but I always think we can learn. We can bring in consultants, we have to, because we can’t know everything. Some of the consultants might not have some of the farfetched ideas that we have, but sometimes others do get excited.

Going back to the element of danger, you did something with projectiles in the 1970s?

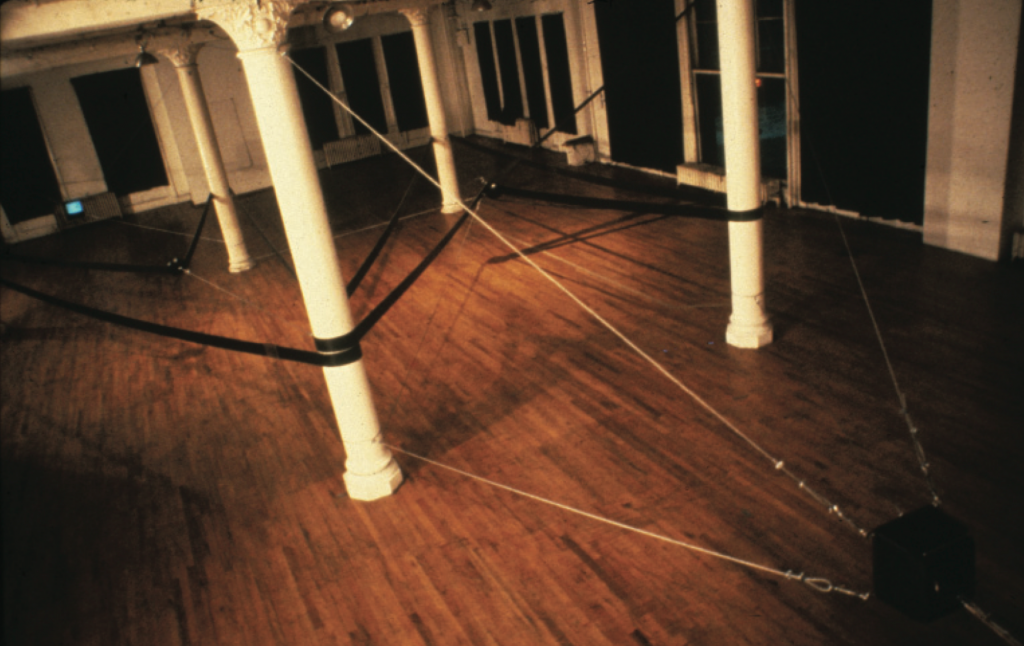

Not projectiles, the one I think you’re referring to, it wasn’t exactly a projectile. It was a piece called VD Lives/TV Must Die. It was a time when I had good titles. Again, these things always had a reason. It was never from intuition, it was always from some kind of logic. It was done at The Kitchen when it was still on Wooster Street. They had a space with five columns in the middle of the space, and I thought, you can’t ignore these columns. So I made the columns the supports for two large slingshots made of rubber bands, each rubber band held in place a bowling ball, and each bowling ball was aimed at a television set. A bowling ball, if it were released, would hit the television set, but if it missed it would go through the window and out into Wooster Street. But nobody released them. Maybe they would now.

VD Lives/TV Must Die, 1978. Courtesy of the artist.

That brings to mind Ant Farm’s Media Burn and the Plasmatics with Wendy O. Williams driving the Cadillac through the wall of TV sets. Did you ever see any Survival Research Laboratories performances?

No, they were reported to me, I knew about them, there were times I was in San Francisco, but I never even met them.

The bowling balls, and S.R.L. around that time they were rigging animal carcasses to walk and blowing things up, and it reminds me of a talk Frank Grow gave at the University of California at San Diego, in 1988 or so, in which he showed slides of S.R.L. performances. The professor, Sally Stein, interrupted him, all in lather, scolding him, saying it was all castration anxiety and masculine acting out.

I don’t think my stuff was about that so much, I don’t think it came from that. It came from wanting a person in the gallery to at least think, and think can I release these bowling balls? Or, do I want to release these bowling balls?

Give them agency?

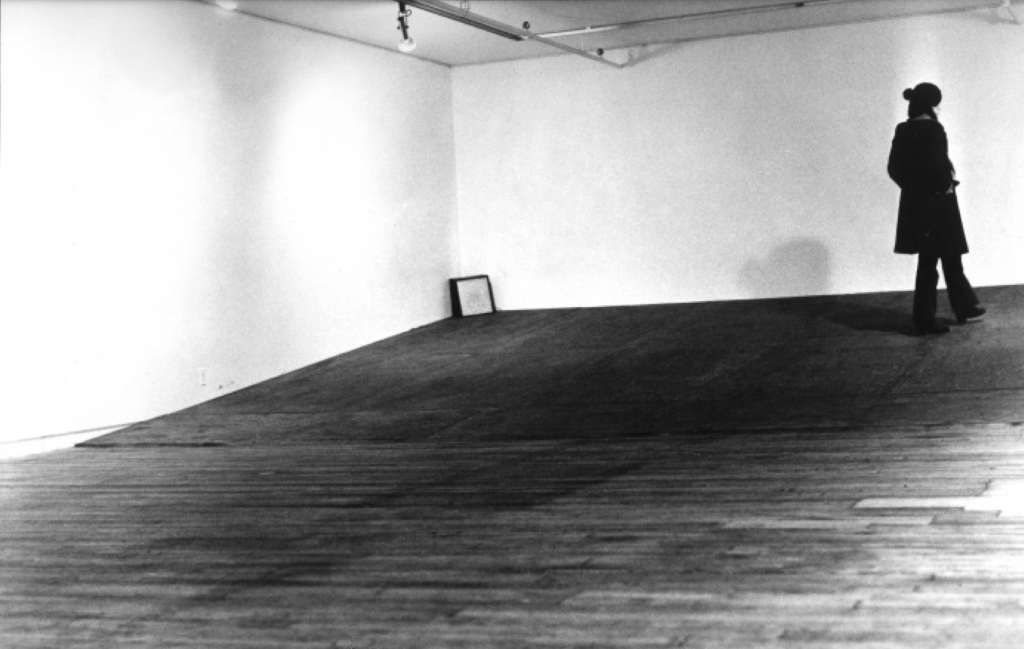

That was so important to me, because I think the worst thing about art is that it takes away agency, though it gives the art doer a lot of agency. I might be blind to certain things, but I don’t think I did stuff that necessarily caused a commotion. Even Seedbed. Seedbed started from wanting to be with people, but not facing people. It was done very logically. I could be in a few places—behind the wall, above the ceiling, or under the floor. Behind the wall seemed wrong since I would be next to people who were by the wall but not next to people on the other side of the room. Above the ceiling was difficult because it had a relatively low ceiling, between nine and nine and a half feet, so if I took three feet, there was only six feet left for people. So it had to be under the floor, but under the floor meant I had to build a ramp. But you know galleries were different at that time, galleries had just opened in Soho. Ileana Sonnebend at first didn’t even ask me what I was going to do. Apparently she was in Paris, and I told people what I had planned and it got back to her, and she called and said, “I hear you’re planning on doing something outrageous in the gallery.” And I said, “I hope I’m not doing it because I’m outrageous,” and she said, “OK.” It was a very different time. She knew that the first year galleries were open in Soho, nobody knew that there were galleries there yet, and of course they needed sales, but they needed sales two or three or four years later. In the beginning they needed attention, and they knew they were going to get attention from things like Seedbed. The same year was the Gilbert and George Singing Sculpture show. They weren’t going to sell that, but they could bring them into the back room and sell them a Johns or a Rauschenberg.

Seedbed, 1972. Installation view, January 1972 at Sonnabend Gallery, New York. Courtesy of the artist.

Seedbed, 1972. Installation view, January 1972 at Sonnabend Gallery, New York. Courtesy of the artist.

In the introduction of Kate Linker’s book (Vito Acconci, Rizzoli, 1994) she writes that she’s going to leave out “the notoriously sexist work of the early ‘70s.” It’s surprising that that statement is in there in a book about you, and also it’s hard to fathom what exactly she’s talking about.

Well, she was a very committed feminist-oriented writer, she wrote about Barbara Kruger and Laurie Simmons. It did bother me. At one point we were kind of friends, but I don’t know if she ever talked about why she thought that.

It doesn’t seem “notoriously sexist” at all, though from that era anything like Survival Research Laboratories, involving violent aggressive tendencies, was deemed sexist.

It was more of a masochistic thing. It was never so much aggressive, though maybe the piece Claim (1971, at 93 Grand Street) was, where I was sitting at the bottom of a stairway saying “I don’t want people to come down here” and every time I heard someone I’d swing the crowbar. But most people thought it was about the Vietnam War. I don’t think it was, except at that time you couldn’t help doing anything that didn’t seem like it was against the Vietnam War. It was so reprehensible, especially to people of my generation, because, you know, I was born during the Second World War, the “good war,” and the United States was the hero nation. A few years passed, and the Korean War, at that time I was maybe nine years old when Truman very justifiably fired Macarthur. And Macarthur came home to parades, it was incredible, we didn’t have school so we could go to the parades. But he came up with great phrases like “Old soldiers never die, they just fade away.” That was a number one popular song at that time. If kids could have voted, Macarthur would have become president. Whereas Truman was a sissy, a guy with glasses.

Claim, 1971. Courtesy of the artist.

There’s a Philip Hamburger story from The New Yorker a long time ago about Truman signing something like 4,000 copies of his autobiography in Kansas City. All day long, talking to everyone separately, with a fifteen-minute break for a tuna sandwich or something. Talk about durational, endurance-based performance pieces.

Switching gears a bit, in the recent Wish You Were Here exhibition at the Albright-Knox museum in Buffalo there’s a sound piece of yours, from 1975, at Hallwalls. There’s also a great Paul Sharits’ Locations called Dream Displacement, with four projectors and audio of breaking glass. He was bi-polar, and supposedly the sound of breaking glass soothed him.

I met him, up there, he took me to this bar where there were nude, or almost nude dancers, dancing around a pole, and at one point I said, “Paul, I’ve got to, I’ve got to get out of here, I’ve got to go to sleep. I know you’re enjoying this, but I’ve got to go.” So I left, and apparently, five minutes later he got beaten up.

There’s also purported tale about Sonic Youth playing in Buffalo in the mid-80s when they showed projections of Sharits’ films behind them while they were performing. After somebody asked, “Who were the projections by?” And they said, “They’re by this guy Paul Sharits, he’s from Buffalo, do you know him?” And whoever they asked was like, oh yeah, and took them over to where Sharits was on the ground practically passed out, wasted, with his head on his knees, his back against the wall, and said, “Paul, this is the band that just played, they want to meet you.” And he flipped them off with both hands, growled, “Fuck you,” then stood up and vomited all over them. And the Buffalo people were all embarrassed, but Sonic Youth was like, “Wow, he’s so cool!”

Sonic Youth formed in, 1981? Wait, I know when they formed, because they formed in my loft. 1980, around the corner, in DUMBO.

In that piece at Hallwalls, and all of your work with your voice it’s very distinctive, your cadence and timbre.

I know, I know how to use my voice. I don’t know how I learned it exactly, but I realized that I was so influenced by things, more voice in movies, especially Last Year in Marienbad. Robbe-Grillet. That text shaped my entire career. I didn’t know it would, but a narrator doing a voice as if it’s kind of hypnotism, because this a person that’s trying to convince this woman they met last year at Marienbad, and at the end she goes away with him. To me that that’s the most supreme, of any kind of art thing. It’s astonishing. The movie came out in 1961, I was a junior in college, I think.

Were you reading Albert Morovia around the same time?

No, I was reading Alain Robbe-Grillet. Robbe-Grillet to me was, he changed the nature of things. That writing could never be the same again. But it didn’t do much. It should have, how could anybody go back to things like Alberto Morovia? But you know Morovia wrote Contempt, which really changed things, once Goddard got to it. If Last Year at Marienbad for me is the greatest movie ever made, Contempt is probably the second. The third, I’m not sure if it’s either Hitchcock’s Vertigo or Psycho. And people laugh at me when I say this, but also Brian de Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise, this rock version of Faust.

We talked about Bladerunner once.

Bladerunner is up there, the art direction, based on Syd Mead.

Do you have a favorite city?

Probably New York. I love Tokyo too, and I do like Hong Kong. But the great thing about New York is, well, I love Tokyo, but it’s hard to see a white person, and in New York you see every possible color, you walk down the street and they’re people walking and you have no idea what nationality they are. There’s such a mix, cities are about mix, and in New York there’s so much incident, I can walk down streets I’ve walked down a million times before and there’s so much to notice.

Do you think the changes in New York, the gentrification, the whatever you want to call it, has diminished that sense of surprise and serendipitous occurrence?

It has lessened it, but I wonder if just the mixing of people in New York can kind of subvert that. Not totally, but to some extent, the great thing about New York is that you can probably get everything though the most terrible thing about New York is the price of space. But only space, you can get food cheap, go to Chinatown, also Indian and Korean restaurants.

It does seem though like at this point New York is almost playing itself in a movie, like a parody of itself.

It could be. You know the Alexander McKendrick movie Sweet Smell of Success?

Of course, with Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis.

That’s like, I know that New York in the movie doesn’t exist but I can’t get it out of my head. I love that New York. But, I had to be more careful when I went out, before. Though I still have to be careful when I go home at 4 o’clock in the morning.

I have a hard time with Brooklyn even if I’m just one subway stop away from Manhattan. And DUMBO, I don’t know, these ridiculous ads—“More creativity per square foot” for Two Trees, the developer.

A friend of mine dubbed it “FauxHo,” she really nailed it.

When I first got here, DUMBO, in 1980, if I was out at night and coming home at say 1 o’clock in the morning, I would take a deep breath. Though it’s only three blocks to the subway station, anything could happen. The first week or so when I was here, a lot of the industrial places had moved out and people had left their guard dogs behind. And in the first week I went out and suddenly this swarm of dogs came up to me, and I thought, shit, what am I going to do? I don’t think they’re going to try and eat me, though they were possibly hungry. Anyway I went into the subway and sat down, and I thought, why is my ass so cold? Then I realized they had torn the back of my pants. So, what do I do now? Do I go where I’m going? It puts you in a quandary.

Do you have a favorite building in New York?

A favorite building? Well, I love the inside of the Guggenheim. I don’t know, I like more in between things, like parts of New York where the grid is broken, parts of the West Village, like where W. 4th street meets W. 10th street. I guess New York is saved by diagonals where everything seems to spread, for a very short time, like around where Storefront for Art and Architecture is, at Cleveland Place. Those surprising places in New York, where it’s still a city but it’s a different kind of a city, there’s an opening. You’re not always in the middle of buildings, though you’re very close.

When I first saw you speak in 2005 you showed something that really made a big impression in a lot of contradictory ways, the New World Trade Center proposal. Where were you on September 11th?

Where was I? I was here, at the studio. I remember going out and thinking, something seemed strange, going to the subway, and realizing, “How come no one is here?” And then going back up, from the subway, I lived on Pearl Street at the time, suddenly I saw people running, and I heard yelling, and this woman saying “The buildings, the buildings, they got the buildings.” And I thought, what is she talking about? But then I could see what was happening at the World Trade Center.

Project for a new World Trade Center, New York, 2002. Acconci Studio (V.A., Dario Nunez, Peter Dorsey, Stephen Roe, Sergio Prego, Gia Wolff). Courtesy of the artist.

When I first saw that my response was a mix of laughing about it, but also, should I be laughing? Even now, but especially then, in 2005, and even more so in 2002 when you did that it was such a sensitive topic. Were reactions really negative? Did people think it wasn’t reverential enough?

I don’t know if I hang around people enough. Seriously, I don’t know what kind of reactions there were. It was part of a show at Max Protech’s gallery, he had asked people to show ideas for the World Trade Center, if you were asked to do something there what would you do. I heard reports that some people said, “You can’t do something like that, it insults the people that died there.” But I thought, OK, once there’s a destruction, can we use this destruction to make a very different space than you could ever make before? Bring the outside into the inside. One column is an elevator from office to office, these are columns are waterfalls from park to park.

The World Trade Center proposal, it had a component of surprise, almost shock, like, “You can’t do that.” It was therapeutic because the humor involved. And there’s a quote from you somewhere, to paraphrase, that you prefer slapstick over irony, the comedic over the tragic.

Well humor gives you, when you laugh, it’s proof that you had some second thoughts. You revised something. You thought things were this way, but maybe they’re not necessarily this way. Laughing makes you do a double take.

Let’s do some free association. You said that for you Godard embodied the 1960s. Who embodied the 1970s?

Who embodied the ‘70s? Probably the Sex Pistols.

The 1980s?

The ‘80s. It wasn’t music. I wasn’t so interested in music then. The ‘80s. It was either Bladerunner or David Cronenberg’s Videodrome.

With the great James Woods. He’s been really quiet lately.

He’s such a conservative, he’s like a republican.

And he was with Sean Young, and then they fell out and she allegedly left dead rabbits on his doorstep and he filed a harassment suit against her.

And she was in Bladerunner! Her presence in that movie was astounding.

Then she disappeared. In another quote, you said that by getting off the page and moving on from poetry you were “finding yourself” and that it was right after the ‘60s, so everyone was finding themselves. You said you had to “go away” to find yourself. Did you ever feel that you’d gone too far, that you couldn’t “come home,” so to speak?

At that time finding oneself really was, you almost had to “go away” to get back to finding yourself. Later I thought I the way to really find myself was through other things. Whether it was through architecture, through landscape, through cities. It’s like throwing your voice.

I thought self was so, so exaggerated in the late 1960s. I started to think all it could do was go around itself. I loved at that time the Van Morrison songs, but I loved just as much the parts that were almost kind of funny, like a beautiful song called “Ballerina.” It’s maybe seven minutes. After about five minutes he says “Well it’s getting late now.” You’re not kidding it’s getting late! Songs are supposed to be two minutes.

Thank God punk rock came along.

Thank God a scream can’t last that long! Maybe the most significant influence of the ‘60s was Archigram, though I don’t think I knew it until a little later.

Your work in the past, and now, with the architecture, the participatory aspect, brings up this idiotic term, relational aesthetics, and a lot of it is a watered down, neutered version of what you and other people did forty years ago. Like, I’m making you Thai food. The things you did, Chris Burden, many others, it just seems depressingly typical how that’s gotten to be such orthodoxy now, a degraded simulation or copy, and garnered so much attention without people saying or acknowledging that.

I don’t know why people haven’t. There’s something so wrong. And one or two of those things, when I stopped by, the food had already run out. I don’t know if the moves Marina Abramović has made are so interesting. If performance can be repeated it’s theatre. I think the best stuff she did was with Ulay. But this recent stuff, the recreations, it’s horrifying. She lies down with skeletons. It’s become a little sad. But she’s become the most well-known performance artist.

That seems like a disservice, the recreations, to what you and others pioneered.

Not just to me, but a number of people. It was kind of interesting, the re-enactments (Seven Easy Pieces, 2005) she did at the Guggenheim, because she approached a number of people, but she didn’t repeat a certain Chris Burden performance. He wouldn’t even talk to her, he wrote her a note saying if you continue this you’ll be hearing from my lawyer. Myself, I said, look, you don’t even have to ask, everybody takes from other things. I admit, I went there, to MoMA, the staring piece (The Artist is Present) and I thought, I just hope she doesn’t see me as she’s staring.

When you were writing poetry, and then started doing art, at that time did you think when I’m sixty-five or seventy I’m still going to be an artist?

I think I thought at that time, what does a so-called body artist do when they get older? I also always thought I want to be doing things that have some kind of continuity, but didn’t want to do the same things. So I was almost positive that I wasn’t going to be doing this when I’m sixty-five. I certainly didn’t think architecture. I think I maybe shrugged my shoulders and said, “Well, I guess I’m doing art now.” But by the time I was thinking I might be doing art but I can’t stay in galleries and museums, because museums are better about history.

Though your work often appears in museums. Have you ever wanted to design one?

Well if someone asked us, yes, we’d definitely try it. But I don’t think museums should necessarily be subservient to the art, there should be more of a combat.

The Guggenheim in Bilbao, at the time it was built people were treating Frank Gehry like he’d invented the next best thing since sliced bread. And when you see it from a few blocks away, wow, it is really staggering. But inside it’s an injustice to the art. It’s anti-art, a violence against what it is purportedly showcasing. Anything that’s two-dimensional and not a huge Richard Serra steel wall gets swallowed up in there.

You know Dan Graham, about ten years ago he said something to the effect that this new architecture, such as Rem Koolhaus, who he had been an early proponent of but then turned against, these buildings are made to look good in photographs, two-dimensionally, in magazines, but aren’t built for the people inside of them. All these museums, like the new Whitney.

Well Renzo Piano did some interesting buildings, but not anymore. Renzo Piano is a particular case, and even in conjunction with Rem Koolhaus, because a lot of those places that Piano is doing were given to other architects first. Rem Koolhaus was supposed to do the Whitney. But anytime someone is fired, now they get Renzo Piano. He’s become the conciliating architect. Really strange that he let himself be that, because he wasn’t always.

Mur Island, Graz, Austria, 2003. Acconci Studio (V.A., Dario Nunez, Stephen Roe, Peter Dorsey). Courtesy of the artist.

Kurt Lewin (German-American psychologist, 1890-1947) with his field theory and studies of group dynamics, that was something that was very influential to you at one time. Is it still?

It was at one time and I still think in terms of it, it hasn’t really left me. I still think, if there are two parties, if there are two people, the way I said before, maybe the architecture and the art have to combat each other, that probably comes from Lewin. He has these very simple drawings: this is one unit, this is another unit, now, if this unit wants to make contact with the other one, this unit can have an extended arm that can go into this unit. But if this unit wants to do more than that, now it can start to wrap around and subsume this other unit. And I still think I think that way.

Your work overall which might to an outsider or innocent bystander seem very disparate, is actually quite connected.

It is.

One of the elements that keeps things interesting with the recent architectural ventures is their connection to what you’ve always been doing, even when you were writing poetry, on the page, and then off the page. Makes it holistic.

To return to the 1980s and Maze Table and Instant House there were a lot of sharp angles, but now there is a lot of the opposite, swirls and curves. So there was a time when it didn’t seem too cuddly and might have hurt the viewer and now everything is really curved.

I, like many people, got really influenced by the notion of topological space, a space where the inside leads to the outside and vice versa, the continuity from outside to inside and vice versa. That kind of continuity interests me. What I wish we could do, but I don’t know how to do, is make a space that doesn’t even have surfaces. Can you make a space out of particles, pixels?

Recently, what you did for Design Impossible in Milan, that’s really wonderful.

You can do that virtually! I want to do that so much.

This might offend you, but it looks almost pointillist, like Seurat, or Sagnac.

Unbelievably, it’s like suddenly I’m an impressionist. I didn’t think it was going to be that, but I saw it and that’s obviously what happens when things become points. That’s what the Pointillists did.

That’s where you’re at right now, in the present?

Yes, but I don’t know how to do that physically. For a long time, a few years, I’ve wished that things could be points and pixels, I wish buildings could be part of the air. I’ve been using the words “thick air” a lot. This Milan project, this is the perfect time, why don’t we go around, and each time you go around there’s one more layer of pixels until it gradually disintegrates. And I called it “When buildings dissolve into air & the air re-forms into buildings.” It’s only an announcement of what it could be, right now.