This interview was originally published in SFAQ issue 11 (November 2012–January 2013).

Legendary filmmaker and video artist, poet, critic, and founder of Anthology Film Archives, Jonas Mekas, often called the ‘godfather’ of American avant-garde cinema, turns 90 this year, and continues to indelibly influence the creation, history, and reception of American culture.

Born in a Lithuanian farming village in 1922, he landed in New York as a refugee in 1949 with his brother Adolfas (1925-2011), after fleeing Soviet police, being captured and taken to a Nazi forced labor camp, and being held in German displaced persons camps.

After discovering avant-garde film and borrowing money to buy his first Bolex, he became intensely immersed in the thriving New York art world with luminaries such as Fluxus founder George Maciunas, Andy Warhol, Allen Ginsberg, John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Salvador Dali, Kenneth Anger, Harry Smith and Nam Jun Paik. Living in the Chelsea Hotel and in the emerging SoHo artist loft collective, he made films and curated film screenings of work by radical experimental filmmakers that came to be known as the classic American avant-garde. A pioneer and iconoclast, he, with his brother Adolfas, published the first issue of Film Culture Magazine in 1954. in 1958 he began writing his “Movie Journal” column for the Village Voice, mostly covering independent, underground film, or what he called the New American Cinema.

In 1962, Mekas co-founded the Filmmakers’ Cooperative, an artist-run, non-profit organization devoted to the distribution of avant-garde film as an alternative to the commercial movie system that they saw as “morally corrupt, aesthetically obsolete, thematically superficial, temperamentally boring”. In 1964, he founded the Filmmakers’ Cinémathèque, which eventually became Anthology Film Archives, one of the world’s most important centers for the preservation and exhibition of experimental and avantgarde cinema as an art form. In addition to contemporary independent film and video, Anthology continuously screens the Essential Cinema Repertory, which Mekas and others formed in the early 70’s, to begin establishing a historical canon of American avant-garde cinema. In Lithuania, Mekas was targeted for his anti-Nazi and anti-Soviet writing and underground activities, and in New York in 1964 he was arrested on obscenity charges for screening Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures, and Jean Genet’s Un Chant d’Amour.

As a filmmaker, he is best known for his visionary “diaristic” films, such as Walden (1969); Lost, Lost, Lost (1975); Reminiscences of a Voyage to Lithuania (1972); Scenes from the Life of Andy Warhol (1990); and his five-hour long diary film As I was Moving Ahead Occasionally I saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty (2000), assembled from fifty years of recordings of his life.

For over twenty years, Mekas has been working primarily with video. Endlessly innovative, in 2007, he began his 365 Day Project, in which he created one video every single day for a year, to be viewed on the iPod and on his website: http://jonasmekasfilms.com.

His recent Sleepless Nights Stories (2011), inspired by reading One Thousand and One Nights, is an episodic series of intimate vignettes of himself and his life with artists and beloved friends, such as Carolee Schneemann, Louise Bourgeois, Patti Smith, Marina Abromovic, Harmony Korine, and Ken and Flo Jacobs. He also has expanded his work into multi-monitor film installations. The Jonas Mekas Visual Arts Center opened in Vilnius, Lithuania in 2007, where much of Mekas’ Fluxus art collection is displayed. He continues to make video work and is currently preparing for numerous upcoming shows, such as a Paris exhibition of photo prints from Williamsburg, Brooklyn where he first lived in NY from 1949-52; an exhibition of installations, prints, and sound pieces and a premiere of his new film Outtakes From the Life of a Happy Man at the Serpentine Gallery in London; and a film and video retrospective at BFI Southbank, London. Re:Voir and agnès b. will be releasing a DVD box-set of Mekas’ films this year.

When I came to New York almost twenty years ago, the first book I read was your autobiography I Had Nowhere To Go. Can you tell me about the experience of being in exile, and if you have a feeling of home here?

Home is where you are. That’s one interpretation. Brooklyn was originally where I landed after postwar Europe, then I moved to Manhattan, and now I am back in Brooklyn. My home, all my new friends are in Brooklyn.

All the places in which I lived are still in my memory; they are pat of me. I am romantic, but I’m not sentimental about the places from which I’ve come. My childhood, Lithuania, my village, it’s all very real, and I use it as material in my work. I do not believe in remaining in one place, none of us do. We all keep moving to somewhere else and to something else.

Exile. There was a period when I was thinking about exile in conventional terms, Like in I had Nowhere To Go. But I have transcended that. Now, I think that it was very good that I was thrown out of Lithuania. It brought me out of a small village with a provincial mentality, and threw me out into the world, and exposed me to unforeseen, unpredictable experiences and realities, which made me who I am today.

If I would not have been thrown out, I don’t know what would have happened to me. I grew up in a small 20-family village, a farming family. I did not experience city life. I had just finished high school. Usually after high school you go to university, but those normal things, I did not have any of it. Suddenly I was there in Germany, together with French and Italian war prisoners in a forced labor camp. Ten years of my life was wiped out. So it was like I left Lithuania at 17, and when I landed in New York I was 27. And that’s where really my life begins, in New York.

My real interest and life in cinema began on the second evening after I landed in New York, when I went to see The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and The Fall of the House of Usher at the New York Film Society run by Rudolph Arnheim. After I landed in New York, with my brother Adolfas, every day we went to the Museum of Modern Art. We did not miss any film opening. When I look to my lists of what I saw then, those lists are the history of cinema. I also went to every new play and every new ballet…

I’ve heard you say it sort of saved your life…

Yes, because, after years in the displaced person’s camps where there was nothing, then suddenly I was here in New York, I was like a dry sponge, I absorbed absolutely everything, I wanted everything, I was open to anything and everything … there was so much … poetry readings and the Beat generation … so much.

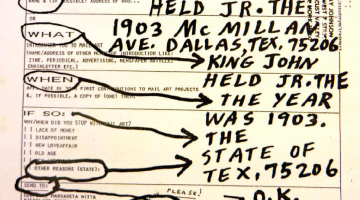

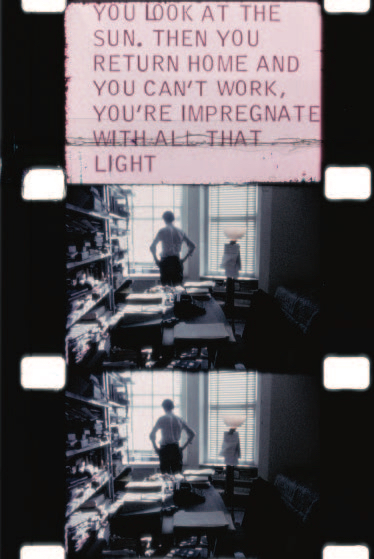

Film still from “Report from Millbrook” by Jonas Mekas, 1966.

Copyright Jonas Mekas. Courtesy of Anthology Film Archives.

Tell me about your relationship with Fluxus artist George Maciunas—who was also born in, and fled, Lithuania, and came to NY at around the same time that you did. How was Maciunas fundamental in the emergence of SoHo as an artistic centre in New York in the ’60s?

I met George first around l95l. In 1954, together with Adolfas, my brother, we began publishing Film Culture magazine. I needed some help with designing, so I asked George to help me, which he did. Ours was always a working relationship.

In l967 he organized the first Fluxhouse cooperative building on 80 Wooster Street. I joined the cooperative by purchasing the basement and the ground floor (total price: $8,000…), where I began the Cinematheque screenings. George fixed up the place, designed the interior. Since he had no money, I gave him one part of the basement to live and work, until 1977, when he had to move out of the city. Most of the Fluxus performances, and much of what is known today as the classic American avant-garde cinema of the Sixties, were first presented

at the Cinematheque.

The Creation of SOHO was 100% George Maciunas’ idea and project. I would say, George was responsible for completely transforming downtown Manhattan. Before his untimely death he created 30 artists’ cooperative buildings that transformed the dilapidated 100 Hell’s Acres area into SOHO. When the idea caught fire and, after a long legal fight—by George—the area was legalized for artists to live in, the idea exploded. Eventually it jumped over Canal Street and gave birth to Tribeca. So it’s all George. Eventually the project cost him his life. After he was beat up by the mafia in one of the buildings, his health was never the same.

George Maciunas on June 9, 1962, Galerie Parnass, Wuppertal, Germany.

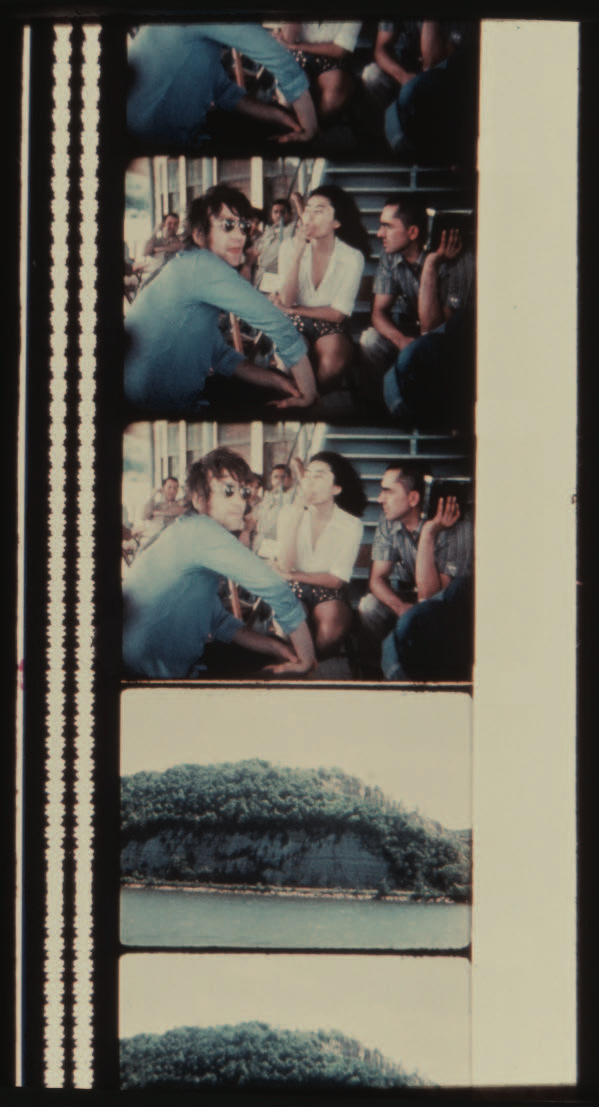

On a Fluxus boat trip up the Hudson, July 7th, 1971, with John Lennon, Yoko Ono and George Maciunas. Courtesy of the artist.

What do you think of how SoHo has changed?

I have been often been asked what would George think about SoHo, seeing what became of his dream of cooperative artists lofts. He would hate it, they tell me. And I say, no no no. George would have liked it! He would have opened stores of Fluxus clothes, Fluxus shoes, Fluxus furniture, Fluxus restaurants, etc. One thing George never lacked, it was imagination and humor.

Can you tell me the story of getting arrested on charges of obscenity in 1964 for screening Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures?

In March 1964, myself, Ken Jacobs, Florence Jacobs, and Jerry Sims, we were arrested at the Bowery Theater for screening Jack Smith’s film Flaming Creatures. A week later, I was arrested again, for screening Jean Genet’s film Un Chant D’Amour. All of us faced six months of prison each. Thanks to Jerome Hill who hired New York’s top criminal lawyer, Emile Zola Berman, to defend us, we managed to get away with six months suspended sentences. And a few days in jail. Susan Sontag and Allen Ginsberg were defense witnesses. Jack was never charged.

I have heard about Jack Smith’s accusations about you, but I have never heard your side of the story. Apparently Smith said that you kept money that should have gone to him, that you used the publicity about Flaming Creatures to further your own career, that you withheld the original film print… Can you please tell me your version of that situation?

According to Jack’s later statements, we got arrested because we wanted, especially me, to promote ourselves… He never mentioned, in those statements, that the idea to screen the film to the public was his idea. He prepared the ads and approved the screenings.

I should tell, on this occasion, that it takes those who didn’t know Jack to believe rumors that I stole his prints and screened them all over without asking Jack’s permission… Those who knew Jack, knew that nobody, absolutely nobody, could have done that—because Jack would have been there to stop it. No work of Jack’s could be presented by anyone without Jack’s permission. He would have been there to stop it.

As for the original print of Flaming Creatures which Jack was telling everybody I stole from him; here is the real story. Jack deposited the original with a film lab in New York that he trusted. But as time went by, he managed to forget which lab it was. Years later, a filmmaker by the name of Jerry Tartaglia happened to work in a place where they collected discarded films from labs. One day among the cans that were delivered from one of the labs, the writing on a can attracted his interest. It happened to be the negative of Flaming Creatures! That’s how the film was saved.

I have to say, that despite who says what, we were friends. Our friendship through the years went through changes, it was a complicated friendship—it wasn’t a friendship of two normal people… But Jack managed to antagonize some filmmakers. In l964, during the filming of Normal Love (with my Bolex…) he promised to distribute it through the Film-Maker’s Cooperative and asked for some advance monies. The Cooperative paid for the film stock and labs and work prints. After the advance (about $2000), which was taken from other filmmakers’ rentals, Jack decided that he was not going to give the film to the Co-op and refused to reimburse the Co-op for the advanced monies. The fact that the money belonged to other filmmakers was of no importance to Jack. Since it was my decision that the Co-op advance monies for his film, I had no choice but to borrow money from friends and reimburse the Co-op. Jack was a genius but he was no angel…

Can you tell me something about your filmmaking process and the diaristic form of cinema?

It’s very simple… There is life around me and there is my camera and there is me. And there are times, moments, when I feel I should film those moments. It’s as simple as that. Well, let’s face it, I film only certain moments, which means that that moment for some reason is important to me, consciously or unconsciously. Mostly unconsciously… It’s important enough for me to want to film it, or—it’s not even wanting, it’s just I have to, I must, I’m driven to film it, I’m forced to film it…

There’s so much said about being in the ‘here and now’, but all the moments that I remember, we did not think about here and now at all—we should forget here and now! That’s when we really live!

What is time then for you?

Time did not exist when I grew up, time began to exist only when I began filming. A roll of film is 2 minutes 45 seconds. 24 frames per second. We never thought about time, in my village. I don’t think about time even now. Time is not important at all. Okay, seasons—there is a time to plant potatoes, what a farmer has to do in the fields, but that’s a different kind of time. You don’t think about time, you just live it. We just did what had to be done. You know the rain is coming and the hay is dry and you rush to take it to the barn. Anything that we did on the farm we did because we loved it, it had to be done. But it was not work. We were not workers at all. Work is a modern invention. Workers were invented by the industrial revolution, and we see the results, it’s a negative thing. If you pay, a worker will produce, will make instruments to torture people, they will make needles to be squeezed under their nails when they torture people. Workers make these things. Workers will make anything for money, that’s why I hate workers.

I have a lot of problems with the word transcendence, but it’s something that I experience with your films, something like a convergence of the past and present, an ecstatic joy of the present, a kind of seeing the everyday as ritual…

It’s not transcendence, it’s the intensity of the moment. It’s intensity. I think I’m an anthropological filmmaker. I’m interested in situations, moments that are like eternal, typical to humanity. It’s not a question of memory, of looking back, but I’m an anthropologist who is interested in certain moments, experiences, behavior, states, and activities that have been performed many, many times by everyone around the world by different generations. And I seem to be attracted to them, to those that I approve, there are certain human activities that I disapprove of and I ignore them—violence, for example—I don’t record them. But there are some activities, some moments, moods, situations, which I want to record as truly as possible. They could be very simple: People being together, maybe eating, singing, where nothing is really happening—but, something is happening there. And I’m interested in those moments, in recording them without destroying or distorting them, without really imposing something else upon them. To record it all as truly as possible, that was and still is my biggest challenge. On my website, my 365 days project, that that was and still is my biggest challenge. I watch for those moments. I go through life, life does not exist for me until suddenly something happens, a moment that I have to record.

Film still from rom “Notes on the Circus” by Jonas Mekas, 1966. Copyright Jonas Mekas. Courtesy of Anthology Film Archives.

Your work seems to celebrate the fleeting, transitory nature of everything: the moving image itself, moments, people. You made a beautiful film of Allen Ginsburg’s Buddhist Wake ceremony. So much religion and spirituality seems to be about trying to deal with impermanence, and I wonder if cinema is somehow a way of dealing with, or accepting impermanence, for you?

I come from a pantheistic background. Lithuania was never really Christian. Nature was always our religion. I consider that organized religions are at the root of most of the horrors that have plagued humanity for millennia. And it’s continuing so today. But I am attracted to the saints, to all those who have achieved high spiritual complexity. It’s a subject that I consider very personal and I prefer not to talk much about it. All spiritual life has to do with an aspect of our very essence which is so complex and mysterious that it is better not to talk about it. I will only say that I believe in angels and I am very close to Santa Teresa de Avila… See my film AVILA, on my website.

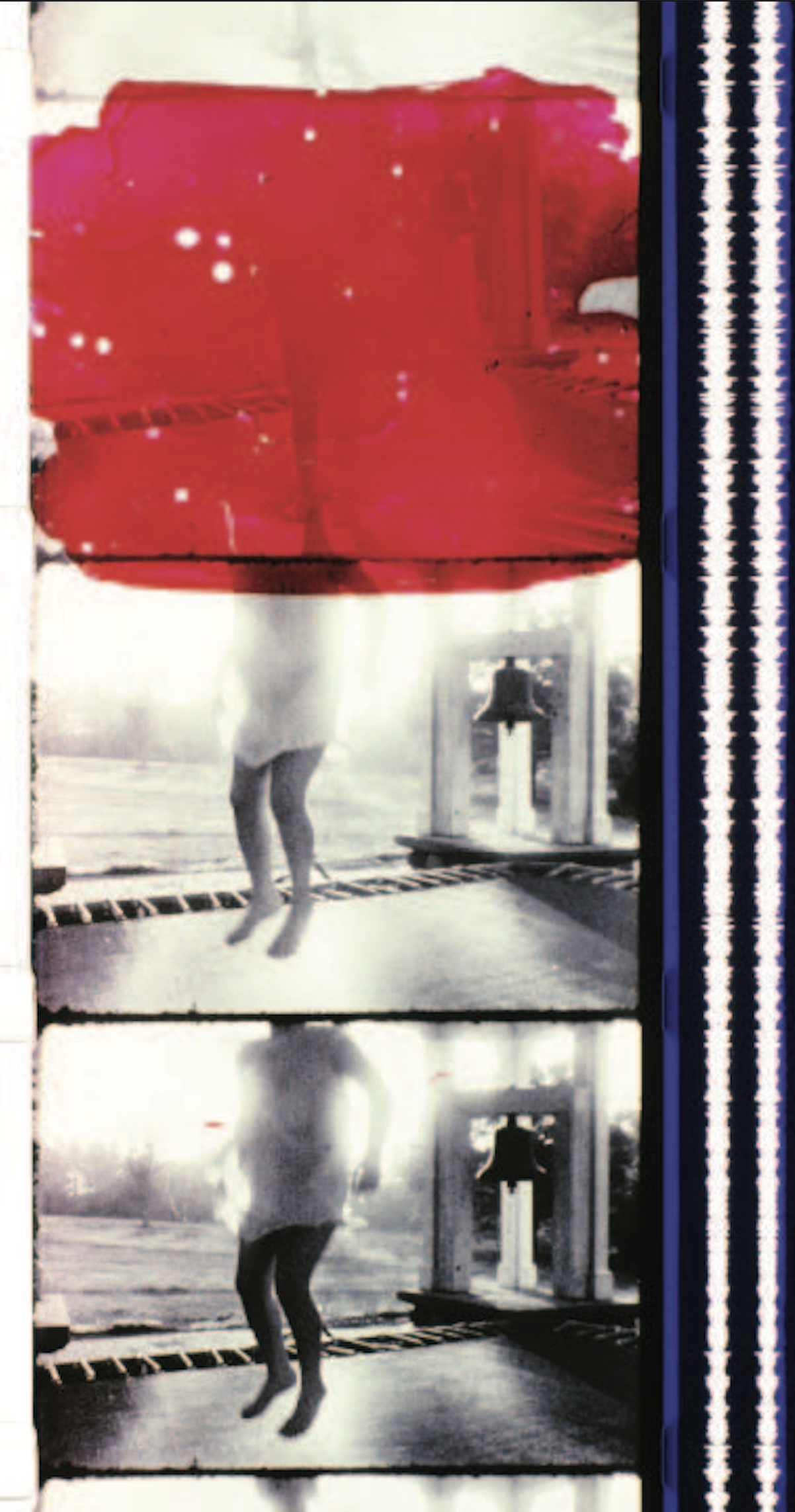

Film Still from “Reminiscences of a Voyage to Lithuania” by Joans Mekas, 1972. Copyright Jonas Mekas. Courtesy of Anthology Film Archives.

Regarding Santa Teresa de Avila … do you feel like you experience anything like her ecstatic or trance kinds of states, when you are engaged in making film or writing poetry?

I do not want to use the word “ecstasy” regarding the moment of filming. It’s more an “immersion,” a total immersion into the moment, into the scene. Same goes for writing. It’s not the same as when Santa Teresa de Avila levitated. But maybe it’s the same. A total immersion in writing or filming sends one into a kind of levitation, you are not here any longer.

I discovered Santa Teresa de Avila by chance in 1966. She came in a smell of roses, she sent me a message, actually, several messages. So I went to Avila and I met her. And she came back with me to New York. With my two guardian angels and some saints who should remain nameless, she has been my best friend since then. Also … a psychic once told me that during the times of Santa Teresa de Avila (in one of my “previous lives”) I was a lieutenant in the Spanish army…

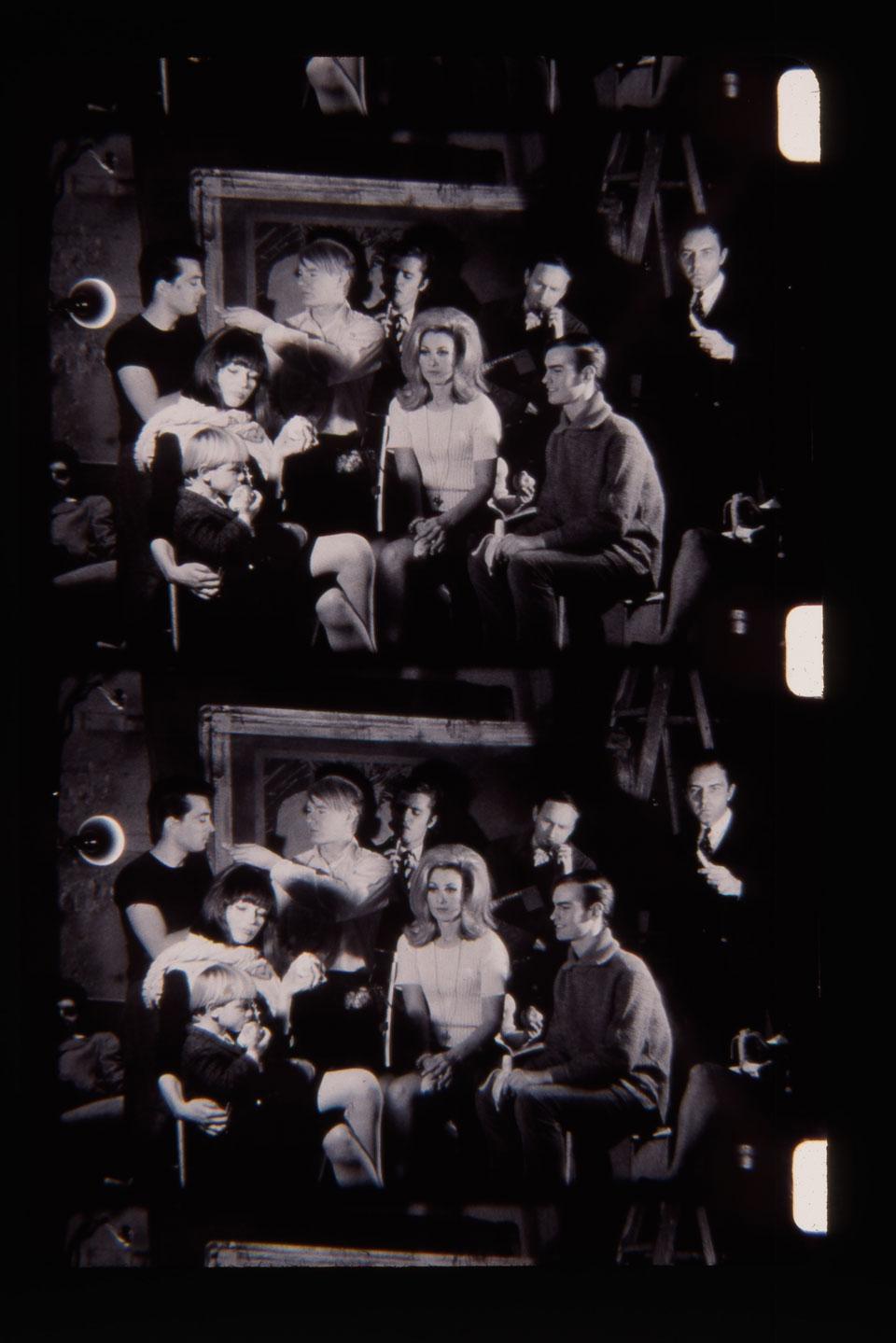

At the factory, December 1964, Andy Warhol, Jonas and others. Courtesy of the artist.

Earlier this year you selected films for a “Boring Masterpieces” series at Anthology. A few of the 60 or so people that came for Andy Warhol’s Empire, stayed for its entire running time of 8 hours and 5 minutes. You were the cameraman for Empire—what was the experience of making that film?

It was the spring of 1964. My loft was the Film-Makers’ Cooperative office; Film Culture magazine office; and a hangout of underground film-makers, poets, people in transit. Bob Kaufman, Barbara Rubin, Christo, Salvador Dalí, Ginsberg, LeRoi Jones, Corso, George Maciunas, Warhol, Jack Smith… I slept under the editing table while the parties were going. A new issue of Film Culture was out and I had asked John Palmer, a young film-maker, to help to carry bags full of magazines to the nearest post office, in the Empire State Building. As we were carrying our heavy loads, the Empire State Building was our Star of Bethlehem: it was always there, leading us… Suddenly we both had to stop to admire it. I don’t remember who said it, John or myself, or both of us at the same time: “Isn’t it great? This is a perfect Andy Warhol movie!”

“Why don’t you tell that to Andy,” I said. Next day he calls me. “Andy is very excited about filming Empire. Can you help us?”

So on Saturday July 25th there we were, on the 41st floor of the Time-Life building. I set up the camera and framed the Empire State Building. Andy was there to check framing. The premiere of Empire had to wait for almost a year. It was a very, very busy period of the Sixties, we kept doing new things, and we had no time to look at what we did yesterday. Ahead, ahead we moved!

So it was only March 6th, 1965 that Empire was first screened. Some 200 people came, but they trickled out, one by one. Still even many hours later there were at least fifty people, and everybody had a great time. Andy was there too.

This past July, on its 30th anniversary, I saw it again at Anthology. The film looked greater than ever. Even today, thirty years later, it remains one of the most radical aesthetic statements in cinema.

Yes, almost nothing happens in it—meaning, nothing in the usual, conventional movie watching sense. The film keeps running, time goes, the anticipation begins to mount: what will come next, maybe nothing will ever come. I had completely forgotten what happens in the film. An hour later, suddenly: an ecstatic moment! The whole Empire lights up! What a moment! What visual ecstasy! The audience bursts into applause…

Later, six or so hours later, when all the lights suddenly go out: amazingly, Empire is still there! It’s all burned deep into our retinal memory…

Why, that day, with John Palmer, why did we look at Empire State Building and say: Ah, this is an Andy Warhol movie! Already in 1964 Andy had established himself as celebrator of publicly recognizable, iconic images, images that everybody saw every day and which had become imprinted in our minds. Be they people – Elizabeth Taylor, Jackie Onassis, Mao, Elvis Presley – or objects such as The Electric Chair or Empire – he was attracted by these images of mythic proportions. Not to make money with them, no: he didn’t need any money. He was obsessed by images.

In 1962 or ‘63, I met Andy on Second Avenue, I was going to a LaMonte Young concert. He said he would join me. LaMonte played one of those very, very long pieces, four or six hours-long variations on a single note. Andy sat through the entire piece. Andy was already doing serial pictures, repetitions of the same image. Stretching time. Jackson MacLow had already written his script/note about filming a tree for twenty-four hours. It was all in the air, Empire. Andy was very up-to-date with what was happening in the arts. One could say that Empire was his conversation with other avant-garde artists of his day, with minimalists, conceptualists, realtime artists and, at the same time, an aesthetic celebration of reality. As such, it will never date, it will always remain alive and unique.

I saw a photo of you at Occupy Wall Street with a sign that said “Money never made anything beautiful… people did!”

Political activities, wars, I have no energy left to pay attention to that. I don’t want to spend energy on it. I am pulled by something else. I know some of my friends, Ken Jacobs, he is very involved in what’s happening in politics. I limit myself in that area only to what’s happening to the planet, ecology, I pay attention to that, but that’s it. I cannot begin to pay attention to Romney or Obama…

I think of what you’re doing in a way as political because it’s supporting the arts, community, a way of life…

There are political activities that are positive … and there are also those that are negative. To me, the positive politicians are those people and movements who contributed to changing humanity, the way of life, thinking, feeling, behavior of humanity … how people like Buckminster Fuller affected the world, how we live and the structures in which we live. Or John Cage or the Beats, even hippies, communal life, women’s liberation. People laughed, dismissed them, but they left seeds and grew roots and are changing humanity. So those to me are the real

positive politics – not what’s known as politicians, political parties, etc.

You are largely thought of as a filmmaker, but you have been working with video for many years…

Around 1990 I began to feel that I had done everything that the Bolex permitted me to do, and that I was beginning to repeat myself, even to imitate myself. Just at that time Myaki, a Japanese friend, offered me a Sony video camera in exchange for a piece of video to advertise SONY. I accepted the camera, I gave them some footage. But it didn’t end there. I continued fooling around with the camera and discovered that this new tool for making moving images opened new areas of content and technique and form. At the same time some of the film stocks that I was used to, began disappearing and I had a difficult time getting used to new stocks. So I embraced my SONY as something that was sent to me by angels, to move me into new directions.

Are you still working with film?

No, I abandoned film in ’89. I saw that video was full of possibilities. When you change the instrument, that changes the content and the form, like if you worked with oils and you switched to watercolors, the subject, the form, the texture, the colors, everything changes. Similarly, 8mm is one thing, 16 another, 35 still another, and then you make a bigger jump from film to video. It opens a different area of content that had not been touched before. As we grow, humanity does not feel the same way about reality and does not see it the same way. As we progress and we move ahead, we want to express, to record those new emerging changing realities. We need different means, we record it with new, emerging technologies. So I see it as a very normal, natural development. There is no need to be sad—oh film is gone! No. Film is there, what was created in film will remain, it will remain with us … that is, if we are wise enough to protect it.

What does working with video allow you to do that film does not?

Video is available to everybody. You can go into any situation without any lights to catch real life, and you don’t interfere. Now you can record and nobody even notices. You can run nonstop video for two hours, that opens new possibilities of recording in time.

Jonas on West 89th Street, 1966. Courtesy of the artist.

What does that do to consciousness?

It allows me to watch and wait for those moments that with film I could not do. With my Bolex, I could not record those anthropological moments, but with video I can. It permits us to record new changing aspects of reality…

In 2007 you did the 365 days project—

In 2007, I made one short video every day and put it on my website, a mad project that I do not advise anyone to do. It was very challenging and demanding to make a film every day, which I did for one year. You can see it on my website, Jonasmekasfilms.com. I continue doing it, but not every day.

What has it been like to put your work on the internet?

Each medium has its own way of being disseminated, be it printed word or video, and the Internet is the perfect way to disseminate video works. That’s why we created the Filmmakers’ Cooperative because nobody wanted to distribute our film works. The same now, Hollywood will screen commercial film, but they won’t screen my work, so the Internet is the place. Every new instrument of making images comes with new content and new form, and of course it comes with new methods of dissemination. It’s not detachable. It did not appear from nowhere, the Internet and digital and computer technologies. There was a need for it to emerge, to be created, invented.

Do you think there’s an intimacy with viewing film that’s lost, that’s different from the kind of intimacy that you see with watching a video on a laptop, for example?

It’s sitting in front of you, on your laptop, so isn’t that intimate?

Well, it’s different. People romanticize sitting in a theatre—

What is intimacy? It’s like this: there are people who say that to watch a western, you have to see it on a big screen. And yes, so many nights I sat in the theater on 42nd Street watching westerns. But then we have George Maciunas—he lived in the basement and he was a workaholic, an insomniac. Whenever I passed by late at night, there he was, sitting and watching on a tiny 7” x 5” television set in black and white, watching westerns. And I was like, really? So I sat and watched with him—and after a few minutes, you forgot the size and where you were, and you were in that other space, it didn’t matter at all, you’re pulled into that image … it has nothing to do with intimacy.

How did you establish the Film-maker’s Cooperative?

In 1962, New York was already bustling with young filmmakers. There were several independent film venues such as Cinema 16, the Charles Theater, Kinesis, Film Forum, etc., where we occasionally screened our films. But nobody wanted to distribute them! The established film distributors thought that our films were amateurish and did not deserve to be seen by anybody. That being the situation, myself and my brother Adolfas, on January 6th, 1962, called a meeting at my 414 Park Avenue South loft, and proposed creating our own cooperative film distribution center. Some twenty filmmakers attended the meeting, and we all voted to create such a center. That was it. The cooperative idea itself wasn’t new to me and Adolfas. Our father in Lithuania belonged to the farmers’ cooperative, and even as a child, when my father didn’t have time to attend cooperative meetings, he used to send me in his place.

There were four or five principles guiding the Film-makers Cooperative: your membership is your film; nobody passes judgment on your film; in the catalog everyone is the same, filmmakers are just listed alphabetically; all income goes to the filmmaker except a percentage that is needed to run the Coop expenses. If somebody calls to rent a film, they have to know what they want, you have no right to suggest A or B filmmaker because that’s not fair. A renter can go to the catalog and take a chance on the description. And it’s run by a board of filmmakers, the work itself at the Co-op is done by a hired Director approved by the board. MM Serra is the Director presently, it became her life, she believes in it. But she is breaking one sensitive principle of the early Co-op; she’s suggesting films to the renters and preparing programs according to her own taste and aesthetics, which is not really in the cooperative spirit, it’s already a personal thing. So it’s not being run the way it was intended.

I’ve never really heard your filmmaking described as documentary—How would you define documentary?

Documentary was a term used to describe films in the 1930’s and ‘40s, when films were made with scripts and footage was collected to illustrate an idea. It was always predetermined. With Cinema Verite, it slightly changed. The new technology permitted you to get closer to real life—but still when one makes a film about somebody in prison, his idea is that prison is no good, the person is probably not even guilty, and he tries to collect material to illustrate that. There is very little real, personal material that is not motivated by an idea. In my case, in my filmmaking there is no idea. I never have ideas and don’t illustrate ideas, and I follow the moments I record so it is personal, diaristic.

Can you talk about Anthology Film Archives, and how the state of filmmaking has changed since starting Anthology?

Here is today’s New York Times, it says, “Film is Dead?”. It says that in the next few years film will be phased out completely in all the movie theatres across the country. It will all be video and digital technology. That makes Anthology even more vital and important. We keep projecting film as film and preserving film as film, but there are very few places left who do that. There are some key art museums, MOMA, there are seven film archives I think in the United States. But even MOMA, they projected Warhol’s Film Tests series on video! I consider that criminal. So it’s important that we are there.

What happens if film as a medium disappears? Do you think there’s a future for it?

It has disappeared already I think. There are no new stocks being made, so when they reach their end, that’s it. It’s all digital now. There is some 8mm, it still exists… in Paris there are people using 8mm, and here too, but it’s small. The film industry does not believe in it, therefore, it will disappear. Kodak survived only because of Hollywood, and when Hollywood switched to digital, Kodak closed. But there should be government, museum archives, they will have to do it—they cannot permit to disappear the memory of one hundred years of humanity.

Is there any danger of Anthology Film Archives not existing at some point?

There is no danger because I was smart enough in ’78 to purchase the building from the city in auction. The building is so well built because it was originally a prison and a court house, it will last five hundred years, we are safe for five hundred years, and nobody can throw us out.

We have two theaters and screenings are taking place in both of them every day. If the day comes that we have to cut down financially, then we’ll cut down the number of programs, but we will still be there. The most difficulty, where we need money the most, is to preserve films, to make screening copies, and for the temperature and humidity control vault. The films can survive for a hundred years, but you still have to make screening copies. We do not screen originals, that would not be responsible because films can be scratched. So now we operate on a $300,000 yearly deficit.

But I’m about to go into fundraising to build a café next door and an extension of the library because we’re very cramped. So the café will help financially because Anthology is suffering financially. I think that the café may help us to repay our debts.

Do you think there’s much interest in film preservation?

No, no. More than ten years ago, but there are very few individuals, such as Martin Scorsese or George Lucas, who are interested in film preservation. The money is in Hollywood, and Hollywood people are not interested in film preservation.

Tell me about the Essential Cinema.

Anthology opened in December 1970, but the Essential Cinema project started about two years before that. The idea was to select key works by key filmmakers, and screen them on a repertory basis. The selection was to be done not by one person but by five [Ken Kelman, Peter Kubelka, James Broughton, P. Adams Sitney, and Jonas Mekas], so that it does not represent one taste. A variety of information and knowledge came into the selection. We spent three years, and we selected about three hundred titles. The idea was to continue in perpetuity, to keep adding new works and go into different areas—documentary, narrative, French, Japanese, Chinese … but then our main sponsor, Jerome Hill, who paid for the creation of Anthology and paid for all of the prints, died. After Jerome Hill died, his foundation, which he used to pay for all of this, decided that it was just Jerome’s whim, totally a waste of money, and they cut the support of Anthology. So there we are, in the middle of this huge dream, and Jerome dies, and suddenly we were at the end of the road, in the desert.

Fortunately, when Jerome Hill died he left us some land in the Florida Keys. So we sold it, for $50,000. I put it in the bank and I said I will keep this for when we really need it. It happened that a building came up for auction, it was in very bad shape … and I went to the auction and they said $50,000! I said yes! The building department said don’t buy it, it will cost you $200,000 to fix, do you have money? No, I don’t have money, but I’m buying it. As it happened, by the time we finished, it took me ten years to fix it, it cost me $1.8 million… but we have it, thanks to Jerome Hill.

Despite the unfortunate fact that the Essential Cinema project had to be aborted, the classic American avant-garde created before 1972 is very well represented and a part of history. These works were created with no support from foundations or state art councils, they were created by the personal struggle of filmmakers.

In retrospect, who would you include in the Essential Cinema who weren’t originally included?

There were many that came after and were not represented—Su Friedrich, Abigail Child, Nick Dorsky, many very, very important filmmakers. Maybe somebody crazy like me will emerge, who will say: I will do everything, I don’t care what I need, what I drink or where I sleep, I want to create the Essential Cinema from 1972 until now… and they can get another crazy person with money, to do Essential Cinema Part Two. But I don’t see such a person, so I guess we won’t have it for some time.

Your childhood in Lithuania…

I’m a farming boy… I grew up in paradise.

Tell me about paradise.

Paradise is paradise … until those that want to improve the world come and destroy paradise. Everybody in my village was happy and singing and dancing and eating well, until the Soviets came. They said, you are unhappy, you are poor, we will make your lives good now! And then they made hell out of paradise.

I feel like maybe something of what your childhood must have been like, lives in your films in terms of nature, in your relationship to nature, it is always present in your films…

If you see Sleepless Nights Stories, you will realize how important nature was to me. I grew up in nature.

How does that work when you’ve lived in the city for so long?

I don’t see the city. The city does not exist to me. I see the stones outside there, I see the trees… the storm yesterday. I don’t see the city. The city does not exist.