In Part One: Collecting, Compiling & the Construction of Cultural Histories, it was noted that artists often find it difficult to retain and manage accumulated materials in their care. Questions regarding materials are particularly challenging for the artist engaged in non-traditional practices. During the discussion in Part Two: The Disposition of Decades-Old Correspondence, our focus was directed to practitioners of mail art and their apprehension over what to do with decades of correspondence and collateral items in the face of institutional disregard. Here, we continue our discussion on how best to fashion a collection capable of soliciting scholarly notice.

Part Three: An Immediately Quaint Form that Excused Itself from History

Larry Miller: Compare Fluxus and . . . high art today.

George Maciunas: First of all, high art is very marketable. You can sell for half a million. You can sell for 100,000. You know, very marketable. Second, the names are big names. They’re marketable names. Like, you just have to mention the name and everybody knows, like you mention Warhol, Lichtenstein, everybody knows. Mention Ben Vautier, even George Brecht, very few people will know. And now even when they say a yearbox sells for 250, there are very few collectors who will collect them, they’re just special collectors of Fluxus things, and they’re willing to pay those prices because they’re just not available any more. But museums don’t buy it. Now high art is something you find in museums. Fluxus you don’t find in museums. Museums just don’t have it. The only exception is the Beauborg and that’s only because of Pontus Hultén, and even then, he has all the Fluxus things in the library, not in collections of art, but in the library (where) he has documents. So he doesn‘t consider it art either; he considers it a document.

[Transcript of the videotaped interview with George Maciunas by Larry Miller, March 24, 1978. Published in Ubi Fluxus ibi Motus 1990-1962. Mazzotta, Venice, Italy, 1990.]

I met George Maciunas a year or so before he granted his final interview, the above excerpt, ruminating upon the disposition of his legacy less than two months before his death in May 1978. It was given after he had departed New York City under tumultuous circumstances, hounded both by the Mafia and the state attorney general, relocating to Barrington, Massachusetts, nearby his foremost American patron, Jean Brown.

I had read about Jean Brown in a 1976 magazine article, which touts her as a collector of the avant-garde, mentioning her interest in mail art and rubber stamps, both of which were beginning to arouse my curiosity. Through her, I learned of Fluxus; I met several of the artists involved in the circle and was instantly enthralled yet befuddled by their inattention by the art establishment when they obviously had so much to offer. I impatiently waited for their recognition for over a decade, until in 1990, the first major exhibition, In the Spirit of Fluxus, was staged at the Walker Art Center and backed by an excellent catalog. Reviews in widely circulated art publications followed, spreading knowledge of Fluxus to a larger audience and attracting institutional attention; these institutions began to collect Fluxus artifacts, driving the price of the works to astronomical heights.

Fluxus 1, the first of the yearbooks Maciunas mentions in the above passage, which he was hard pressed to sell for $250, sold in 1993 for $25,000, a hundred-fold increase, reflecting the prestige Maciunas had attained since his demise. Before his death, Maciunas was committed to depositing significant collections into private hands, including those of Jean Brown, Barbara Moore, Marvin and Ruth Sackner in the United States, and Hanns Sohm in Stuttgart, Germany.

Soon after the Walker exhibition, Jean Brown sold her comprehensive collection of Fluxus to the Getty. She insisted that the whole of her assembled materials be acquired, including a sizeable selection of mail art. As Maciunas foretold, it was not the Getty Museum expressing interest in the material as art, but the information wing of the museum, the Getty Research Institute, charged as a repository of documents.

Julie Paquette, Fluxus Buck, c. 1996. Collection of John Held, Jr.

Barbara Moore sold her significant collection to Harvard University. Hanns Sohm’s collection was bequeathed to the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart. Years later, another large Fluxus collection, derived in part from the resources of Barbara Moore and Jon Hendricks, was donated to the Museum of Modern Art in New York by Gilbert and Lila Silverman. But as early as 1988, MoMA’s Director of the Library, Clive Phillpot had surreptitiously exhibited Fluxus, much to the consternation of the museum’s curatorial staff upon discovery.1

Fluxus still exerts an influence on the contemporary art scene. Fluxfests are convened by mail artists positing themselves as neoFluxists, just as Fluxus, reviving the spirit of Dada in the early 1960s, were labeled neoDadaists. Marcel Duchamp, arguably the most decisive artist of the 20th century, was subjugated to a similar protocol of neglect, having to wait several decades before his inclusion in modernism’s conversation. The progression of art history is a slow march, entailing a long slog toward acceptance into the canon. It is one I witnessed firsthand with Fluxus and am currently experiencing with mail art.

As an art medium of inclusion that avoids judgments of quality, mail art has eluded critical attention, marketability and widespread institutional interest. In a 1984 review of the book, Correspondence Art: Source Book for the Network of International Postal Art Activity, by Mike Crane and Mary Stofflet (Art Contemporary, 1984), cultural historian Greil Marcus commented that, “The history of contemporary mail art is the history of an immediately quaint form that excused itself from history.” Distaining established art hierarchies and seeking alternative paths of cultural production and dissemination; mail artists found themselves adrift from conventional routes of mainstream acceptance.

There has yet to be a comprehensive exhibition of mail art in a major American museum, with only a scattered interest from European venues, most often in national postal museums. Despite this, the medium continues to flourish, extending the boundaries of art with a continued practice of global social engagement, generating a multitude of small edition publications, producing exhibition documentation and distributing small-scale artworks.

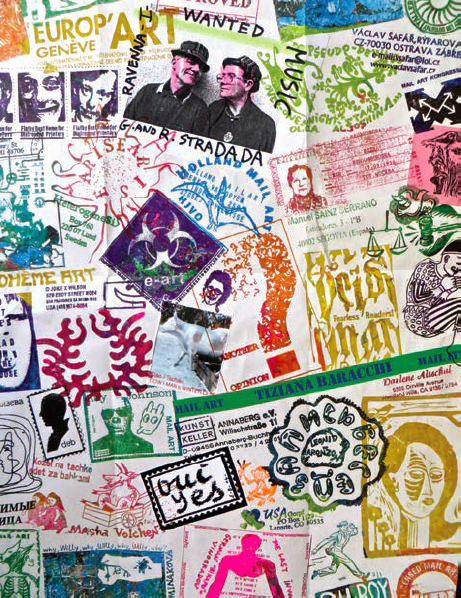

There are many avenues to roam in mail art’s Eternal Network, which harbors multiple marginal art forms including rubber stamp art, artist postage stamps, artists’ books, periodicals, add & pass collaborative works, project documentation, painted works, sculptural objects, and collage, just to name but a few of the concerns which continue to engage this global network.

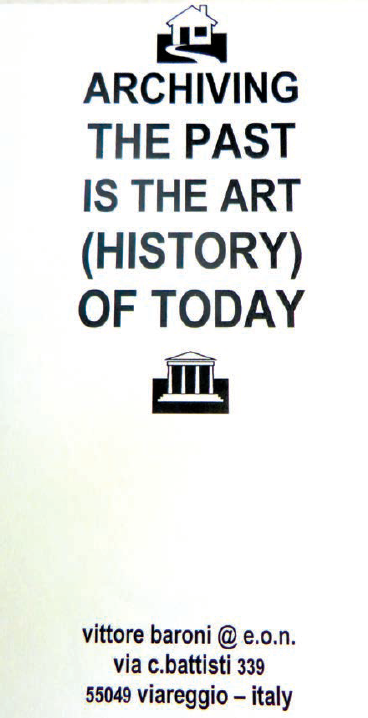

Vittore Baroni, Archiving the Past is the Art (History) of Today, 2013. Collection of John Held, Jr.

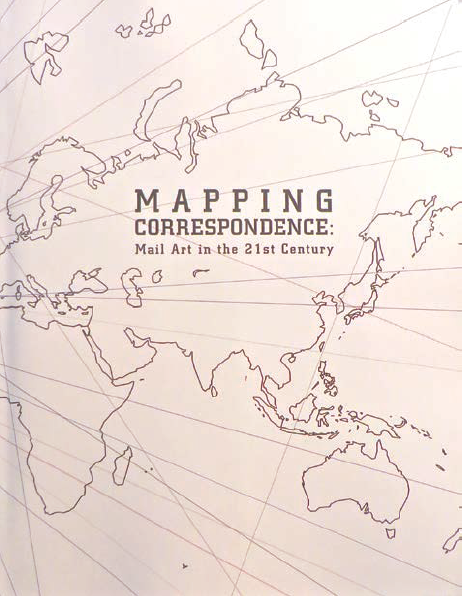

Mapping Correspondence: Mail Art in the 21st Century (New York: Center for Book Arts, 2008). Collection of John Held, Jr.

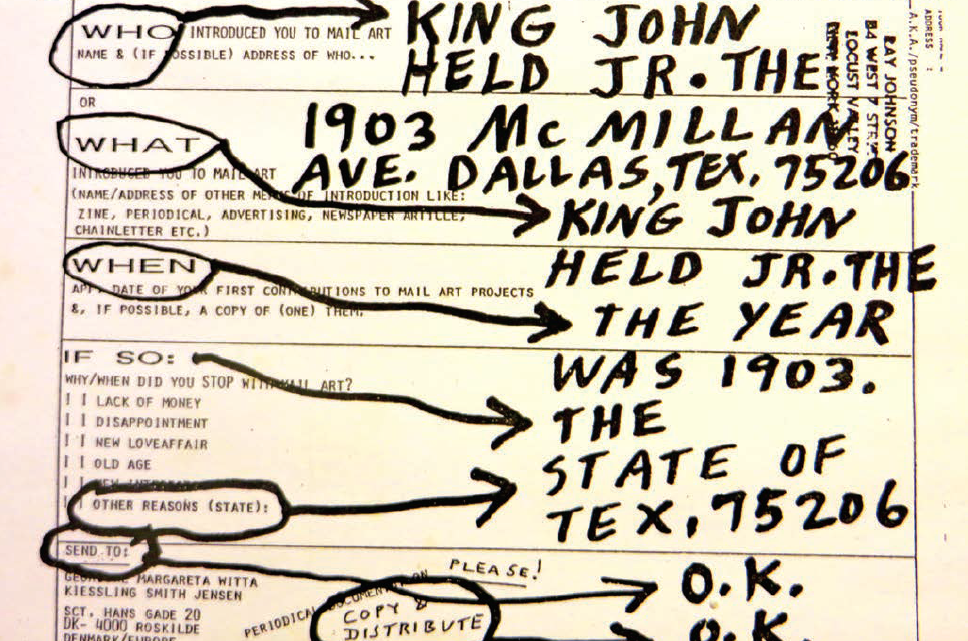

Maturing under the tutelage of Ray Johnson and the students of his New York Correspondance [sic] School in the 1950s, many of whom were associated with Fluxus, mail art has developed an enviable record of creative output and documentation yet to be sufficiently examined by scholars. The march toward institutional incorporation often occurs by singling out an individual typifying the ideals of the area of interest under scrutiny, and this has begun to happen with Johnson.

Ray Johnson has become increasingly canonized since his death by apparent suicide in 1995. A highly acclaimed film, How to Draw a Bunny, has extended his reputation far beyond the dismissive, “most famous unknown artist,” appellation, which followed him in life. A 1999 retrospective at the Whitney organized by Donna De Salvo (currently serving as the chief curator of the institution) furthered his renown. Representation by the prestigious Richard L. Feigen & Co. gallery enhanced his standing, garnering critical acclaim though posthumous exhibitions increasing the marketability for his more formal collage works, which often incorporate postal motives.

Mail art has gained in stature with Johnson’s increased success by association. Other early practitioners, many of whom have passed away, have also attracted the attention of respected cultural historians. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in their 2015/16 exhibition, Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960-1980, included many artists engaged in mail art, such as Luis Camnitzer (Uruguay), Paulo Bruscky (Brazil), Ulises Carrión (Mexico), Felipe Ehrenberg (Mexico), Milan Knížák (Czech Republic), Endre Tót (Hungary), Clemente Padín (Uruguay), Pawel Petasz (Poland), Liliana Porter (Argentina) and Edgardo Antonio Vigo (Argentina).

Introductory texts for the exhibition stated that, “During these decades, which flanked the widespread student protests of 1968, artists working in distinct political and economic contexts, from Prague to Buenos Aires, developed cross-cultural networks to circulate their artworks and ideas. Whether created out of a desire to transcend the borders established after World War II or in response to local forms of state and military repression, these networks functioned largely independently of traditional institutional and market forces.”2

In exhibiting the works of cultures usually excluded from modernist discussion and institutional acquisition, relevant materials were drawn from a number of sources outside of the museum’s permanent art collection, including MoMA’s library, which contributed periodicals to Transmissions. Under what circumstances they came to be placed there, is next to be revealed in our continuing examination of mail art’s assimilation in institutional collections.