Matthew Palladino is from San Francisco and has been living in Philadelphia for the last couple years. He’s about to move to NYC. His work has been exhibited at Park Life and Eli Ridgway Gallery in San Francisco and Fredericks & Freiser in NYC. This following interview was conducted in March 2012 by Jamie Alexander, owner of Park Life, and friend of the artist.

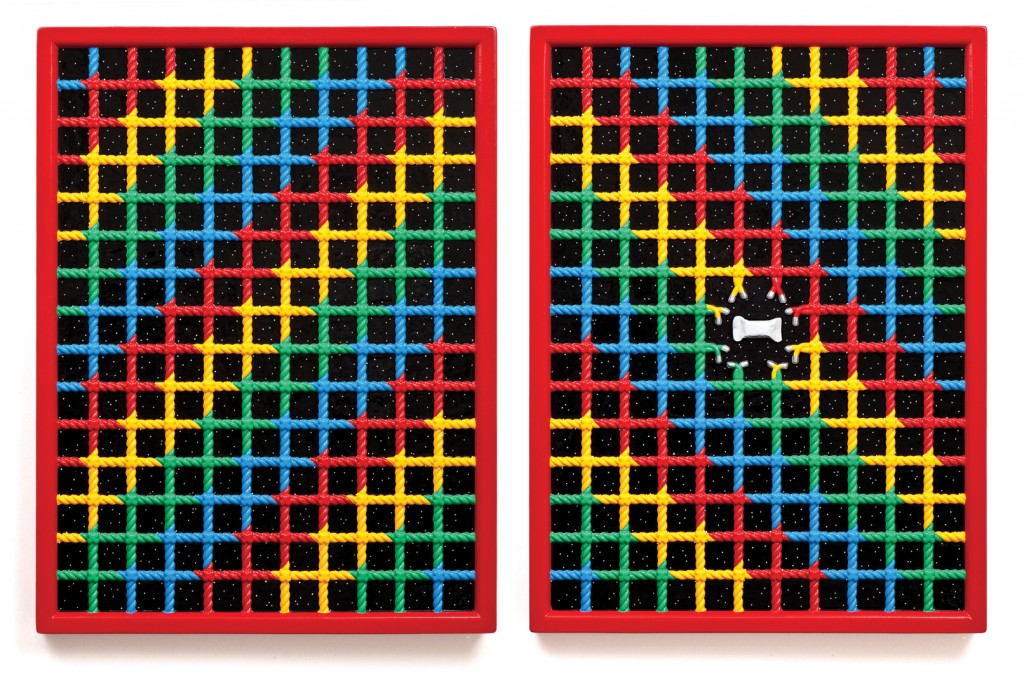

Matthew Palladino, “Bounce House”, 2012. Enamel and plaster on panel. 2 panels, 40 x 30 x 2.25 inches each. Courtesy Eli Ridgway Gallery

I’ve been following your work since I first saw it at your Brown Bear show in 2007 and I’ve noticed that the content of each body of work you present has a unique narrative, almost unrelated to the previous body, but always seemingly very personal. Can you talk about the elements and narratives of your work?

I’m not sure how to make work impersonal. Or maybe I find it difficult to get excited about things that I don’t feel some real connection to. For some reason, words like narrative and illustrative sound derogatory to me, though they tend to be some of the more common descriptors, especially of the earlier work. It’s like, if you’re a serious singer/songwriter and someone says “Oh, I just love your jingles!”. You appreciate their enthusiasm, but you think, I’m trying to write real songs, not jingles, you know?

Your visual painting style can be described flat and colorful with some folk or outsider-art qualities. Can you explain how your style developed or what influenced it? Is there any relationship or influence from SF’s Mission School artists?

In high school, people like Margaret Kilgallen, Chris Johanson, Barry Mcgee definitely had an affect on me. Their work had a similar feel to it as the work that had hung on my parent’s walls when I was growing up. It just seemed to click. The work just felt so earnest, unpretentious, without need for explanation or justification. When I was younger, that was very inspiring.

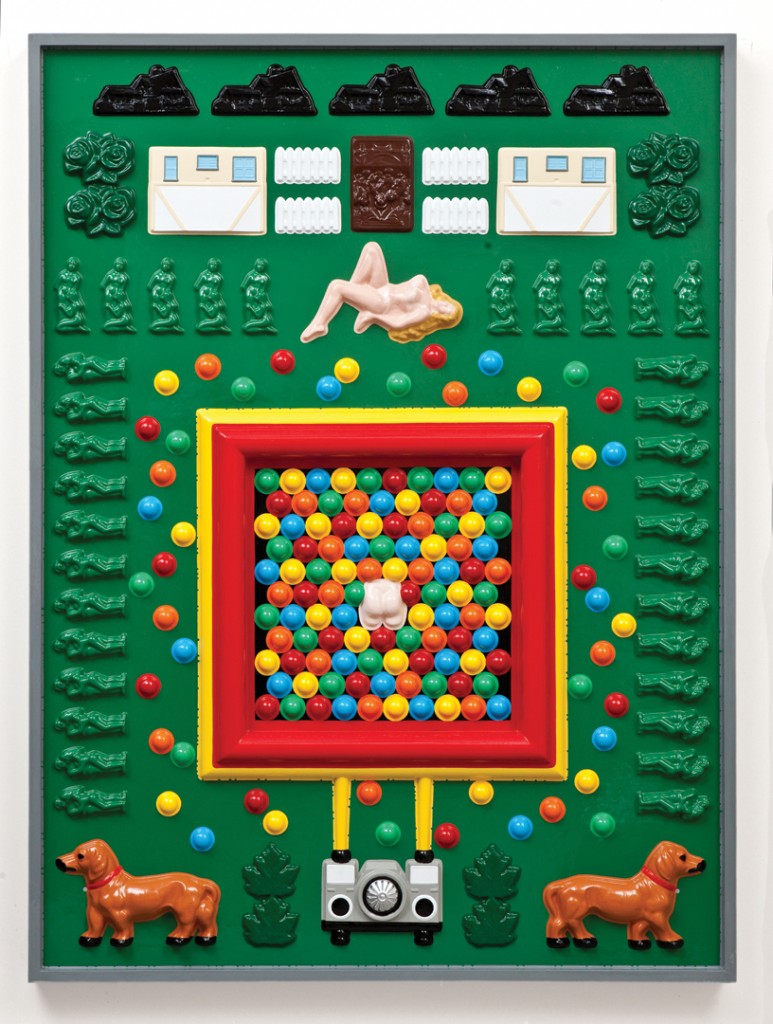

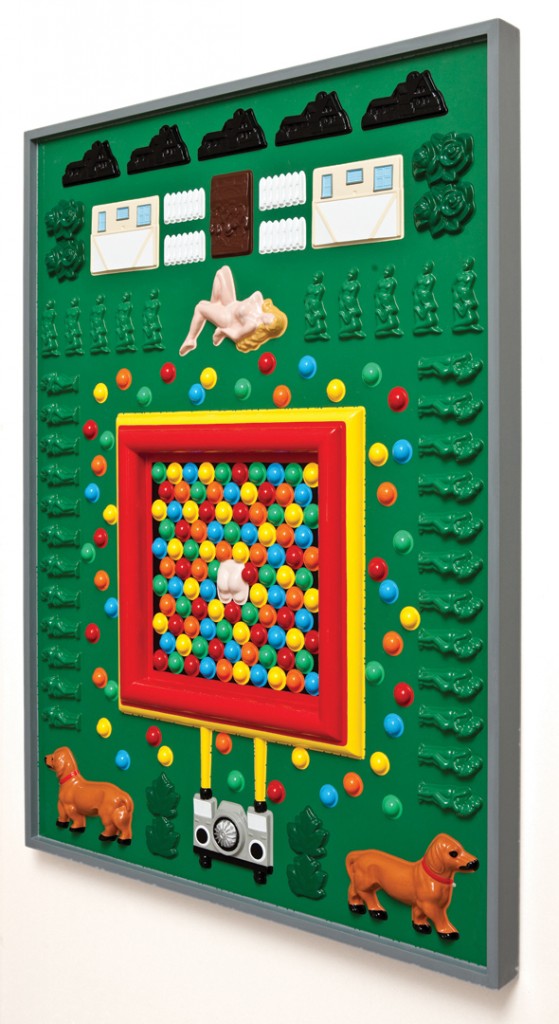

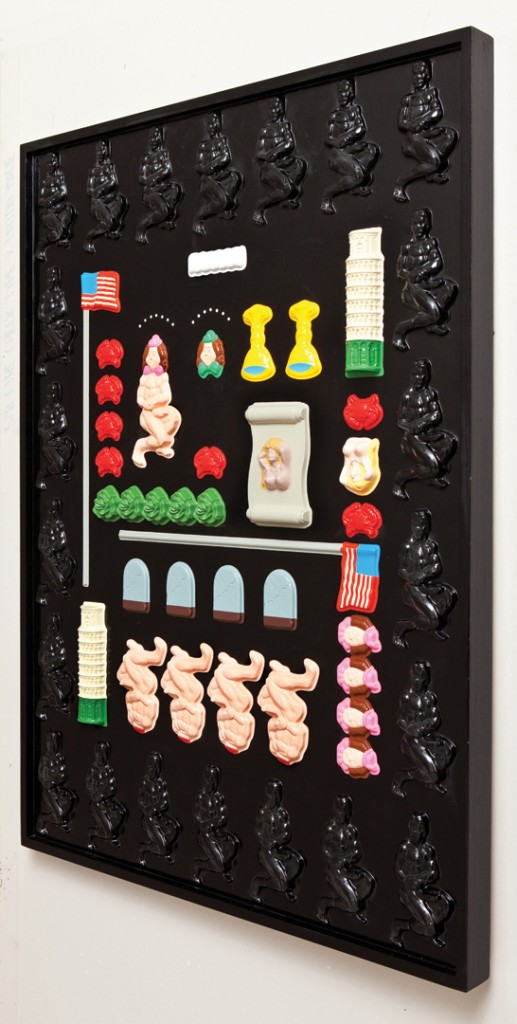

Matthew Palladino “Ball Pit”, 2012 Enamel and plaster on panel 48 x 36 x 2.25 inches Courtesy Eli Ridgway Gallery

Matthew Palladino “Ball Pit”, 2012 Enamel and plaster on panel 48 x 36 x 2.25 inches Courtesy Eli Ridgway Gallery

It seems that with each new body of work you increase the level of effort in scale, medium and content. These new pieces at Eli Ridgeway gallery even moving into 3-D relief. Is there a drive to keep moving that bar higher or just experimenting with new technique?

The works scale, medium and the level of time committed to it is directly affected by my own resources. I didn’t get into watercolor and ink on paper because I had a special affinity for it. I got into it because it was the cheapest way for me to make work at the time. I didn’t have any money for supplies back then, and it was easy to steal watercolors from the art store, you know? Paper is relatively inexpensive. But as time has gone by, and I’ve made a little money, I’m able to take that money and put it back into the work. If I had endless time, money and space, the work would reflect that.

It’s important to keep things interesting too. I’m miserable making the same thing over and over. I’ve tried. The problem is that people sometimes favor a certain grouping of my work over another, and they want more of that. But by that time the works evolved into something else. So I find myself, especially with this newest body of work, trying to assure people that this is just the next step in the work. Not a gimmick or a one-off, but another mutation of the thing that came before it. And that hopefully the work will always be in a state of change.

You spent some time at CCA in the Bay Area. Can you talk about what that experience meant to you and what did you learn from it?

I only got to spend 2 years at CCA. The friends I made there were probably the most lasting, positive I got from attending art school. I didn’t really hang out with anyone my age who was interested in art before I went to college.

There’s an infamous teacher over at CCA, Franklin Williams, who made a big impression on me. Very eccentric guy, but a wonderful teacher. His classes were very loose. There would maybe be model or something, but really you could do whatever, then he’d walk around the room and interact with people individually. The first day he had us do some still life drawing then had us put them all up on the wall. He then would pick certain ones and expound on them. It was an introductory class, so it was a mix of the different disciplines, people who’d never done life drawing. So I thought mine came out pretty good, I’m feeling confident, like, I got this one. But when he got to me, he started making fun of it. “This guy thinks he can draw!” Ha ha ha.

This treatment went on for pretty much the rest of my time in all his classes. Until then I had gotten nothing but praise and encouragement from adults when it came to art. But he was really hard on me. He’d either tear me down, or completely ignore me. I hated it. He’d baby others, telling them how well they were doing to keep going then he’d just pass me with a grunt sometimes. But he recognized what each individual needed. He saw that my pride needed a kick in the ass, that the work was too precious, and that if I wanted to make work that was truthful rather than pleasant, I’d have to be willing to take risks and to fail. And that’s something I’ve aspired to do ever since.

Matthew Palladino “In The Night”, 201. (Side View) Enamel and plaster on panel 48 x 36 x 3 inches Courtesy Eli Ridgway Gallery

I know the artist David Huffman also had an impact on you and your work during your time in the Bay Area. Can you talk about that? Were there other artists that influenced you?

I met David at a turning point in my life. As I said I had spent two years at art school, but had just dropped out due to financial complications. While my friends continued their education, I moved back into my parent’s house in San Francisco with no money, no job, and no direction. Sort of the same situation that people are in when they graduate college, free of school and commitment for the first time in their lives, but lost when confronted with integrating into the real world. Except I didn’t have a degree or any sense of accomplishment and there was no one else in my life who could really relate at that point.

So, I actually started going back to CCA and trying to see if I could audit some classes. A couple of my friends were taking a class with David Huffman so I dropped in. I guess we hit it off. I didn’t really know him, but he had actually been the student of Franklin Williams back in the 80’s so we bonded a little over that. He was cool. He let me hang out in the room during class while I worked on my stuff.

I had just seen a documentary about Jim Jones and Peoples Temple and it had had this profound affect on me. I’ve talked about it in another interview already so I won’t get into it here, but it shook me. To this day I still can’t put my finger on what it was that moved me to the extent that it did. It had the effect of churning up all this shit that started coming out in my work. I was second guessing myself, wondering if this was appropriate stuff to show to other people, all these spiritual and racial ambiguities popping up. But David was very encouraging. His work deals with race. I think being a black artist teaching a largely white group of students, he got a kick out of me trying to tackle some of these things. He told me go for it. Who cares what other people think?

What is it that you’d like people to get out of the art you make?

The work I make is not like science, it doesn’t begin with a question. It instead tends to end in a question. It feels more poetic than scientific, though I suppose art is the thing that lay between them.

It’s clichéd, but I don’t make work with other people in mind. I, of course, hope the work, once done, is appreciated. But my desire is to manifest something into existence that was not there before, that because it solely exists in my mind, cannot exist without my action. My process, while I get a lot out of it, is not the focus of the work. It’s a means to an end.

Looking at the work, it’s obviously important to me that it has an immediate impact that draws the viewer in, that it engages you at first glance. But once engaged I hope the work causes them to wrestle with their own ambiguities and confusion, as I do when creating the piece. I hope that people have a sense of dissatisfaction that lingers with them afterward, a sense of the mysterious and the absurd. Like a very realistic dream. That’s how I feel everyday. Even better if they come to a conclusion, though. I love when people inform me, with authority, what’s going on in my work.

How has moving away from the Bay Area changed your perspective on the art world, if at all?

I don’t know that living in another city has affected my perspective on the art world as much as participating in the art world has changed my views. Art fairs were a real eye-opener for me. When I went to Miami for the NADA fair, I had no idea what to expect. I quickly found out that the fairs not really geared towards the artists, they’re more for everyone else in the art world…the collectors, curators, galleries, museums, writers, everyone else… To see the mix of the political/business side of the art world at that scale was new to me. I realized making great work was only a part of being a successful artist.

And NADA was a great fair! Probably the best I’ve been to. A lot of high quality work all in one place. And people there were nice, not stand-offish at all, very encouraging. But then, going to Miami Basel, it was even more heightened. Very bourgie. Not many young people. Little European men in expensive sun glasses with their plastic-looking wives all done up. The women were all wearing very beautiful shoes, I remember. I spent more time people watching than looking at art. People were standing in front of the art with their backs to it half the time. It was a bit gross to me. And these are the people that rule the art world. People with money, with cultural capital, people with connections. I guess I always knew that, but to see it all in person made me question if this was the community I wanted to aspire to please.

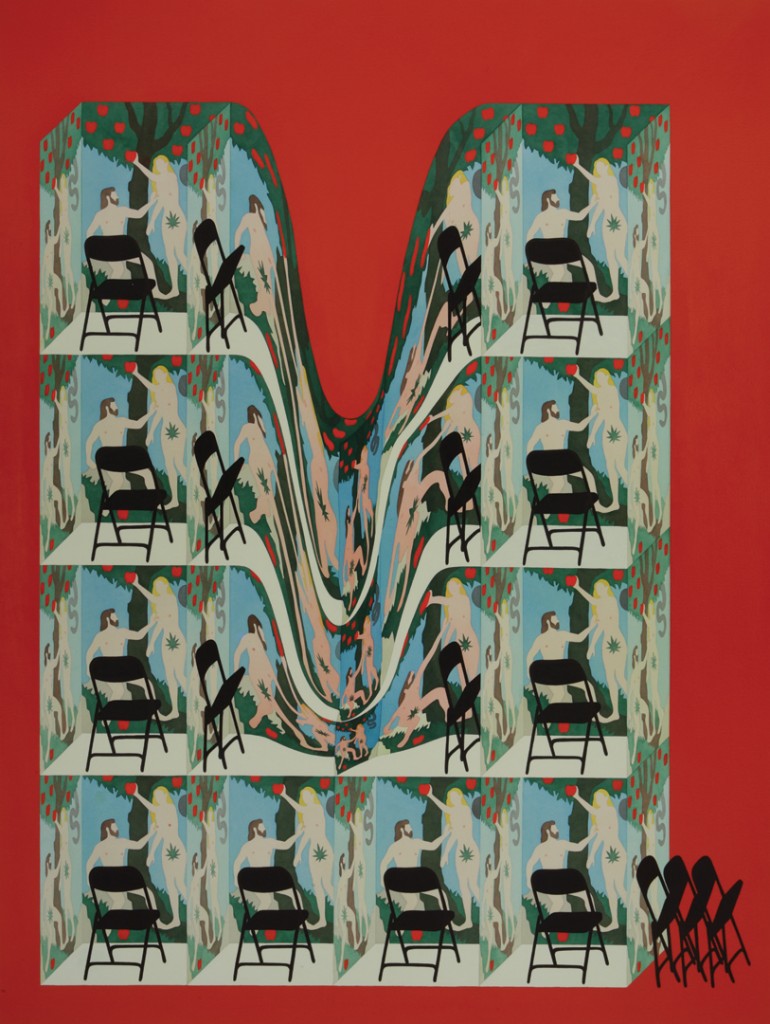

Matthew Palladino, “Private Pleasures 1”, 2010, Acrylic ink on paper. 49 x 37 inches. Courtesy Eli Ridgway Gallery

What do you think of the relevancy of the Street Art Movement?

I don’t really take much notice of it. It seems like most of it is visually derivative and usually espousing some uninteresting pseudo political view. I’ve always liked graffiti though. If you follow graffiti, you know the aesthetics of something is only a part of that world. Scale, location and amount are all equally in play. With “street art” aesthetics seem to be the primary focus, maybe with a little illegality thrown in for sex appeal. Street art seems to pander to public opinion while graffiti attacks it. So for me, while there are some very notable exceptions, (Espo’s “Love Letters” in Philly for one) I’d take graffiti over street art any day.

It sounds like you grew up in an encouraging environment, artistically. Your sister is an artist too right? Was being an artist something you wanted to do from early on?

My parents have always been very supportive of the arts, and are both artists in their own right. My father is a musician at heart and a programmer by profession. My mother writes poetry, and paints and draws when she’s not working at UCSF. And my sister, Zoe Rose, is an incredible singer/songwriter. She’s already a star in my mind. I’m bracing myself for her eventual fame.

There was always an emphasis on art growing up in my house. Music, theatre, visual, literature, I think it’s just that that was where their passions lay, which rubbed off on me and my sis. It was always made to feel important. They never made it seem like pursuing a life in arts was any more or less worth while than any other job.

I’ve been consistently impressed with your technical ability. Your Wonder Box paintings from your first Ridgway Gallery show are amazing in the details. Is this a natural skill or something you honed at school?

Thank you! I appreciate that. But I don’t think natural skill exists. It’s more about what obsessions take hold over the rest. I do believe I had a natural interest in the visual that at some point over-road my other interests. And because that interest was recognized and encouraged, I was able to focus on it, commit myself to exploring it, and from that an intimate familiarity and understanding evolved.

What do you think you would be doing if you weren’t creating art?

Humor seems to be my overriding obsession. Everyone in my family is very funny. I hope the work doesn’t come off as jokey, but there’s an undercurrent of humor that I think comes through, a certain amount of absurdity. If I wasn’t making art, I would love to be a behind the scenes kind of guy in the comedy world… the editor on Tim and Eric Awesome Show. Or the show-runner on Strangers with Candy. Or the late Mitch Hedberg’s agent. Or the guy who brings Stephen Colbert coffee. Something like that. Those people are my heroes.

What sort of work are you working on now? More relief works or returning to paper?

No paper for now. It’s the furthest thing from my mind at the moment. I do love to work on paper, but the ideas for objects moved past the limitations of that medium. As an artist, I hope people will come along for the ride, regardless of things as minor as medium. But I guess that’s not always the case. People who are truly supporters of my work, and not just the skills I’ve amassed in one medium or another, seem as excited as I am of moving forward into new worlds. I’d actually like to do even more sculptural, space-filling work, money permitting.

What do you think of the current state of contemporary art?

I really don’t know. I tend to follow my friends’ and acquaintances’ work, and through them their friends’ work. So I’m not as informed as I could be. It seems like technology and collaboration seem to be dominating interests of people who write about contemporary art. The internet and other new technologies will continue to reshape the ways we perceive, make and share art. But I don’t think it will change the function of art fundamentally.