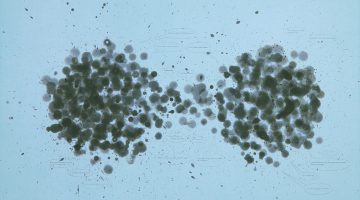

Tea Party, 2012

2-color lithograph

Paper size: 48 3/4 x 37 1/8 in (123.8 x 94.3 cm)

Image size: 32 x 22 1/2 in (81.3 x 57.2 cm)

Frame size: 51 x 39 1/2 (129.5 x 100.3 cm)

Printed by Jungle Press Editions

Courtesy the artist and Leo Koenig Inc., New York

Nicole Eisenman’s show at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive presents a fundamental reshaping of a beguiling, simple word that we use on a daily basis. After viewing a stunning selection of Eisenman’s recent oeuvre, the very word “artist” comes into question as a category of aesthetic positioning, identity, and sociopolitical stance within our modern capitalist regime. She destabilizes the term even as she herself is an artist. Eisenman uses her penchant for subversion to at once undo and reify the importance of the visual arts in posing those unanswerable questions that must be considered in an era marked by forgetting and erasure. As Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art and Phyllis C. Wattis Matrix Curator Apsara DiQuinzio points out in her evocative text to accompany the exhibition, the pieces included all “coalesce around the theme of social and economic hardship,” specifically with regard to the inability of capitalism to maintain any sort of equity on either economic or psychic levels. It is a problem that artists have wrestled with for centuries – how can one depict injustice when painting, printing, and sculpting are inscribed in the very regime of commoditization that has left us scarred by poverty, fear, and disillusionment?

Nicole Eisenman

“Guy Capitalist”, 2011

Oil, mixed media on canvas

76″H x 60″W

Gallery Inventory #EIS189

Courtesy of Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects

Photo credit: Robert Wedemeyer

It follows that MATRIX 248 is paired with Ballet of Heads, a companion exhibition that firmly places Eisenman’s practice within a centuries-long history of which she is simultaneously a participant and an outsider. Even as her work appears within the walls of a museum, she is at the vanguard of undoing the Artist, not through a trite rejection of ownership or genius, but rather by striking at the word at the very moment of its creation, that instant wherein the art object placed itself under the purview of the grotesque-comical Guy Capitalist (2011). Many scholars have pointed out that the emergence of the autonomous “artwork” and the concomitant creation of the term “artist” were inextricable from, as Professor Amelia Jones of McGill University describes it, “colonial exploits and developing structures of capital and related discourses of individualism” (Amelia Jones, Seeing Differently: A History and Theory of Identification in the Visual Arts. New York: Routledge, 2012. 23). For artists and critics in the early years of what we deem the discipline of art history, self-sufficiency was critical in separating the “fine arts” from “decorative arts,” a rhetorical move that had as much to do with patronage as it did the centralization of knowledge and taste-making. In this way, artistic identity was forever tied to class, capital, and stratification. Eisenman’s purposeful subtleties present us with the failures of the very discourses that allowed the visual arts to create their own delineated space. She presents us with something at once beyond and within art, and in so doing returns the conversation to the inventive uncertainties of the medium.

Nicole Eisenman

“Tea Party”, 2011

Oil on canvas

82″H x 65″W

Gallery Inventory #EIS192

Courtesy of Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects

Photo credit: Robert Wedemeyer

DiQuinzio’s incisive selection of a range of media perfectly encapsulates the paradox with which Eisenman contends – the impossibility of utilizing a medium born from elitism and essentialism in order to depict, for instance, the ragged, terrified, yet strangely placid, denizens of a makeshift bomb shelter in Tea Party (2011). With their stockpile of ingots overlaid in real gold leaf, this becomes less about making fun and more about the beautifully complex interaction between painting and the public sphere. These figures have within their grasp the very financial security that they seek in the form of Eisenman’s applied gold, yet they would have to exit the confines imposed by paint in order to access it. Perhaps, in Eisenman’s dystopian genre scene, pigment is as imprisoning as the musty basement itself. Art and capital are thus intertwined; the painting becomes a commodity and the artist recognizes her own place within the lineage of art’s commercial fetishization. Sitting on the shelves above these ignorant, yet painfully human, survivalists are stacks of Bumble Bee tuna, a modern-day Merda d’Artista, Piero Manzoni’s infamous 1961 readymade long believed to be canned shit sold by its weight in gold. This is more than caricature; instead, Eisenman points to the nuance inherent in the art object’s entry into an increasingly complex political-social-aesthetic arena

The Triumph of Poverty, 2009

Oil on canvas, 65 x 82 (165.1 x 208.3 cm)

Courtesy the artist and Leo Koenig Inc., New York

Dr. Thomas Huerter, Omaha, NE

It is clear, then, that this exhibition represents the efficacy of Eisenman’s deft handling of the impossibility of art and artistic identity. Doubtless aware of the fraught past that precedes her, Eisenman bravely implicates her own chosen profession in a widespread inability to cope with the Great Recession and its fallout, thereby calling to mind the fragility of the archetypal Artist and his deeply problematic origins. Art, however, is certainly not an outmoded means of engaging with the world. For Eisenman, it is the forge for a necessary recasting of contemporary discussions of art and politics through productive and rigorous critique.

MATRIX 248 is on view at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive until July 14, 2013 . William J. Simmons can be reached at wsimmons@nullcollege.harvard.edu and on Twitter at @WJ_Simmons. Most recently, he is the author of “DESIRE” for the exhibition “Jimmy DeSana: Party Picks” at Salon 94 Bowery, New York.

For more information visit here.

-Contributed by William J. Simmons