I walked into Eduardo Consuegra’s studio on an unseasonably warm day in Los Angeles to find he has been working quietly and consistently on a new body of work that is ready for the eyes of the world. As the light of the golden hour that afternoon made its way through the skylight and across the wall, it highlighted three distinct practices that define his work. Ranging from minimalist abstract painting, collage and assemblage, to representational painting, Consuegra explores the visible and veiled aspects of the dissemination of images. Using found Colombian magazines from the ‘70s and ‘80s as his primary content, he has located a space to address the ideologies of advertising and modernism as it translated into and out of South American culture. By looking at the ways that modernism and the transference of cultures dictate modes of thought, Consuegra explores the inherent desire to possess or experience, and it is apparent across his mediums. It is through this constant troubling that Consuegra makes meaning of the influences that dictate culture and identity through the appropriation and negation of images.

Eduardo Consuegra, “1+1=2,” 2011. Plywood, wood, mirrors, 28 x 60 x 36 inches (71.1 x 152.4 x 91.4 cm), EC0211.

Consuegra was born in Bogota, Colombia, and spent his early life as a photographer documenting the effects of modernism and the changing landscape of Bogota. When he moved to California to go to art school, he began using a variety of methods to create elegant, formalist artworks with a contemporary twist. One source of Consuegra’s work is his collection of Colombian magazines, “Semana” and “Cronos,” similar to “Time” and “Newsweek,” “Architectural Record,” and “Escala,” an influential source for promoting modernism and international architecture in Colombia, among others. His use of the magazines and advertising pages is a delicate intervention, creating new narratives focused on translation and difference made to function independently of their circulation. In his appropriation of images, the work is bled from its source, and the allure of formal aesthetic choices literally re-frames and re-broadcasts cross-cultural advertising through the politics of display.

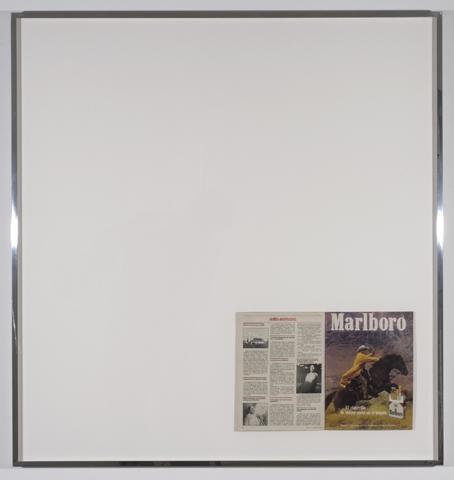

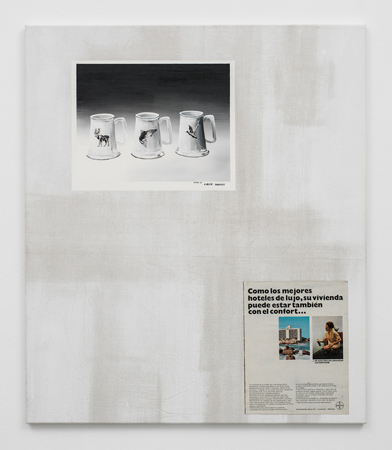

In his last two exhibitions at Richard Telles Fine Art, Los Angeles, “In Bond” (2008) and “Re-Present” (2012), Consuegra used his practices to create more complex relations between images—or lack thereof—and their fundamental structures. To create a discourse, Consuegra made paintings in relationship to the magazine pages, such as one canvas with painted beer mugs and an advertisement pulled from a magazine for a luxury hotel in Spanish. There were a group of collages where a large sheet of brown paper was folded to fit inside of a frame, then vintage magazine pages were inserted to fit into the folds. To complement these found and repurposed objects, Consuegra made several starkly abstract paintings using a large-format brush and oil paint that he would pass over the canvas once, twice, three times to duplicate the effect of the mechanical process of a scanner. Alongside these paintings the always awry and ever-so-off-center found advertisements from North and South America leaves room for the images to circulate within what Consuegra calls the “effects of an un-calibrated machine that is showing stress.”

Eduardo Consuegra, “Untitled (Tavern),” 2012. Oil and magazine page on linen, 40 x 36 inches (102 x 91 cm), EC1012.

What I saw in his studio continues these explorations but goes even further, digging beyond the façade to explore the beginning ideologies and mental processes that create images. In a new series of paintings and collages, Consuegra has begun to forego language in favor of symbols—symbols that represent the principals of images and how they translate into an intricate web that infiltrates our daily lives. For one, a series of new collages builds upon dozens of magazine pages, loosely layered one atop another, to the point that they are almost completely obscured. The top layer is a found black-and-white photograph whose central image has been cut out. On the panel next to the collage is a painted interpretation of the removed photographic center. These collages and assemblages sort of duplicate the way we experience images, one after the other, after the other, ad infinitum.

The vintage magazines remain bound, left open to specific pages, in oversize metal frames next to complex and precarious sculptures made of mirrors, wood, and foam. There are also dualities at play—double images of similar ads from North and South American magazines situated side by side—that create a disjunctive dialogue with each other. Published during his childhood and after he moved from Bogota, the work of the magazines begins in the personal, even biographical, context of Consuegra’s childhood then move into more spatial concerns. The need to document the past and even revise it into the present is one form of opposition that appears in Consuegra’s work.

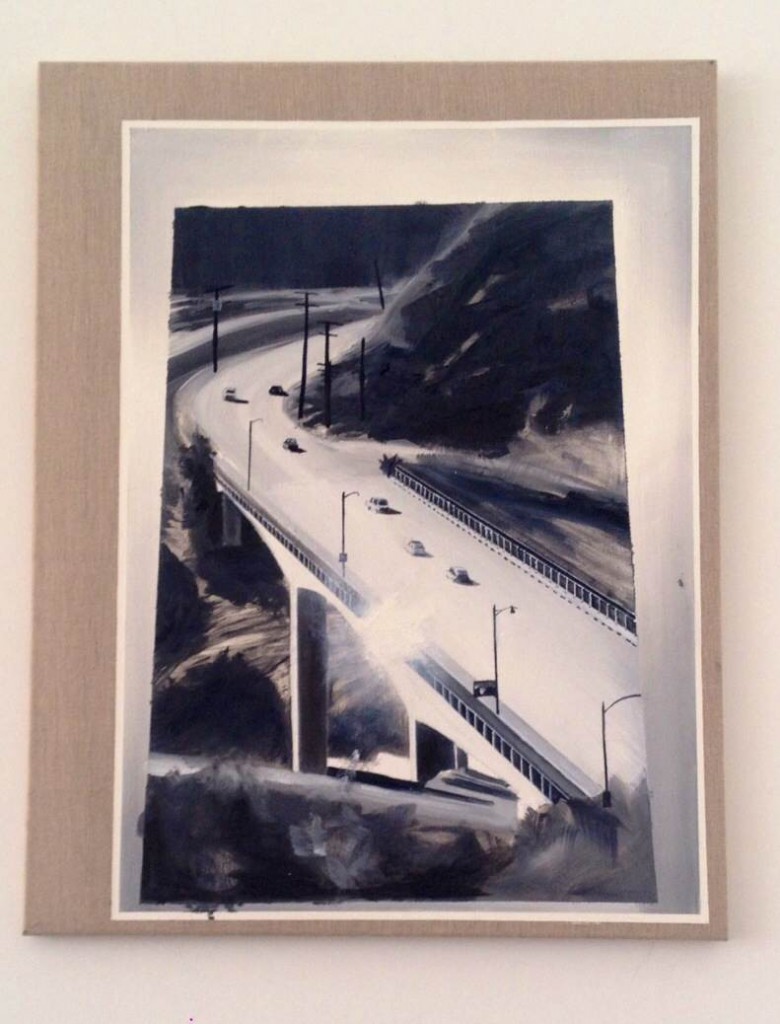

In a new series of representational paintings, Consuegra photographed images from the pages of books of modernist architecture across Latin America—Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; São Paulo, Brazil; Santiago, Chile; Havana, Cuba; Asunción, Paraguay—and painted them in a way that reveals the origin of the photographs. In black, white, and gray, they are not made to be perfect renderings. Each has a slightly askew perspective, a slanted corner here or the cropped edge of an adjacent image there, the natural edge of the linen canvas framing the image into its place. They are further obscured and confounded by a subtle glare, the familiar white spot from the reflection of a light’s flash on glossy catalogue paper. While the source becomes clear through this reference to photography, the paintings visually distance the original image and measure the architectural era of each building. These painstakingly rendered paintings signal the passing of the period into a new era of unknowns. They not only address the desire, utopian ideology, and reality of modernism, but also its failure—and the underlying linkage of politics to Latin American modernity.

Eduardo Consuegra, “Untitled (2%), 2011. Framed magazine page, 24.5 x 26.5 inches (62 x 67 cm) EC1311.

Though he does not claim the work to be overtly political, Consuegra acknowledges the search for meaning in the exploration of history. In our visit he mentioned a quote by Walter Benjamin: “Memory is not an instrument for exploring the past but its theatre. It is the medium of past experience, as the ground is the medium in which dead cities lie interred.” In his disparate practices, the oppositions of the un-calibrated machine showing stress, or the rupture of the politics of modernism, his images seek to revise the successes and failures of images to transfer ideological meaning from the most abstract to the truest representation. Whether in decay or thriving in their current forms, the oppositions Consuegra creates are the ones in which we live and thrive within, our own connections to the political meanings that surround us.