Carrie Mae Weems: “Subject & Witness”

Gallery Paule Anglim

14 Geary Street, San Francisco, CA 94108

Marc 19—April 19, 2014

Carrie Mae Weems consistently challenges the narratives of history and representation. Her works shift fluidly between delicate and overt confrontations of established sexual, racial, and political structures. As a photographer, Weems uses the camera as a recorder of the inescapable yet malleable lineages around her, and as an activist tool in reflecting on the state of African Americans today. Inseparable from the absence of positive black visibility in the dominant chronology of the United States, she has stitched together her own vision through representation, performance, and the examination of overlooked and altogether absent realities.

Through many works in the show and in her career, the interpersonal connections that work within and break established understandings are portrayed and reconfigured. As observer and performer (both are actively participatory), she is an explorer of untold stories existing within those that have become unquestioned paradigms: male and female, government and citizen, artist and viewer relationships are all equal points of consternation. From either side of the camera, Weems creates informed critiques of dominant power structures.

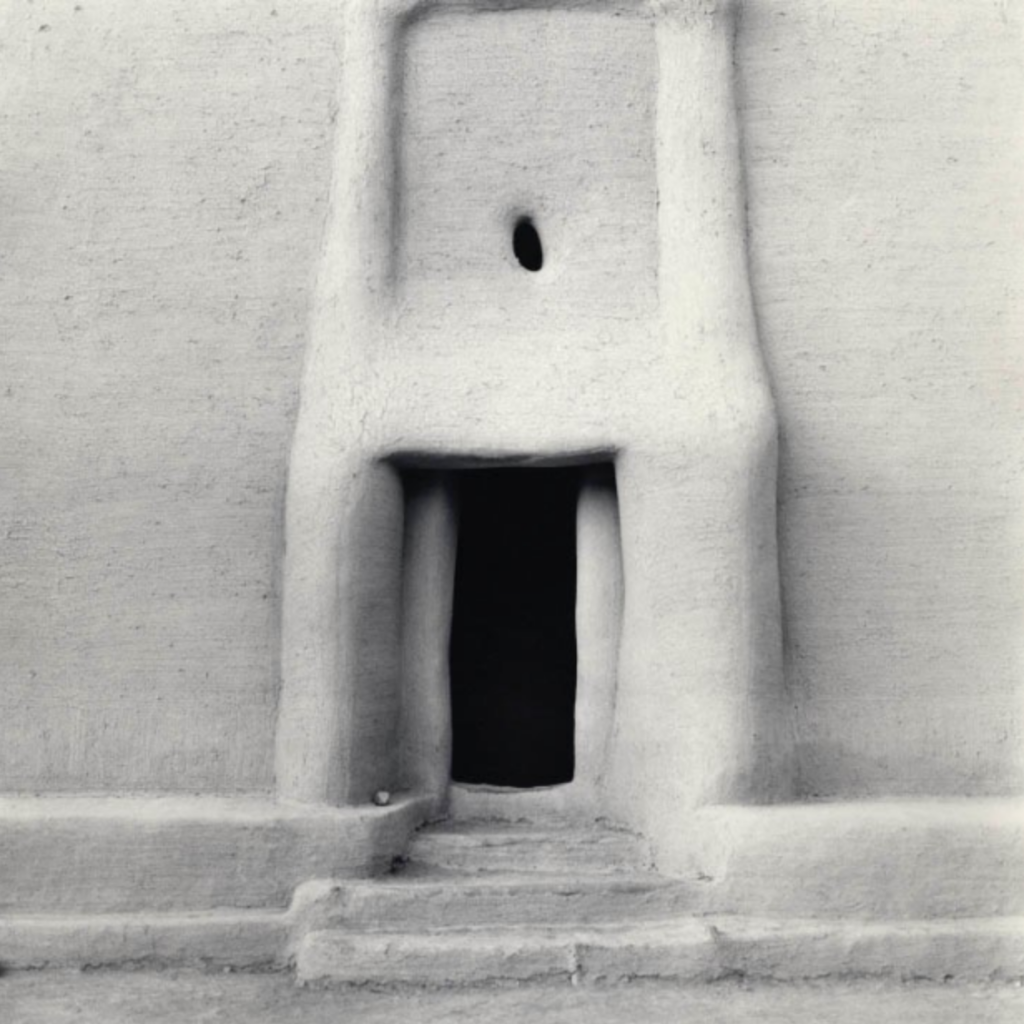

Carrie Mae Weems, “Shape of things (female),” from “Africa Series” (2000). Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Paule Anglim.

It is through the encapsulation of Weems’s work at Gallery Paule Anglim—a kind of truncated retrospective—that we come to understand her continuous effort. Hers is a constant message, a call for the realignment of social consciousness in the face of catastrophic oppression. Walking through the space, moving first from photographs of architecture that illuminate a gendered, African creationist story through the sexualized nature of vaginal entryways and phallic columns (“The Shape of Things”), to the last room housing images of silhouetted 19th-century owner/slave figures in various domestic situations upholding class-based relationships (“Louisiana Project”), Weems’s omnipresent political vision solidified.

Carrie Mae Weems, “May Flowers” (2003). Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Paule Anglim

“May Flowers” is a portrait of three young African-American girls in traditional poses of beauty and relaxed contemplation (think Manet’s “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe”). Each holds a different gaze that bonds one with another, one with the viewer, and one with the sky—that potent space of innocence and daydreams. Part of a larger project entitled “May Days Long Forgotten,” the girls are also shown dancing around a maypole, wearing crowns of flowers, and generally celebrating spring. Using propagandistic images of smiling children employed by the Soviet government for aggrandizement and social control as a historical platform, Weems inverts the intentionality as a call to action for global human rights.

Carrie Mae Weems, “Galleria Nazionale D’Arte Moderna,” (2006). Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Paule Anglim.

What is impressive in nearly all of these works is the layered accessibility and the extensiveness of meaning. In a suite of formulaic images taken of the artist in full view from behind, always in a black dress, we stand as counterparts in observation with her and of her environment. In two instances, “Galleria Nazionale D’Arte Moderna” and “Louvre,” created while traveling abroad, Weems stands before the most iconic museums of art in Italy and France. As establishments for modern art and the encyclopedic survey of human creation, respectively, the failure of these organizations lies in her presence alone. Her ghostly figure and hesitant entry signifies the questionable function of both institutions, each largely dominated by the works of white men. If these edifices of pedagogy are overwhelmingly filled with one perspective, where does hers belong? What narratives are really playing out within the walls of these internationally adored buildings?

Carrie Mae Weems, “Louvre” (2006). Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Paule Anglim.

The power of “Subject & Witness” lies in the constant alternation of long and short views; in the singular images and the ties between years of information. Taking a sweeping view of the main room in the gallery, the thread that links every body of work clicks together. Weems is a contemporary artist for the reality of this world—there is no hiding behind the thin veil of ignorance.

Her slight encoding (we are not necessarily force-fed imagery of violence, or slavery, or institutionalized sexism) creates accessibility and linkages to painful subject matter and calls for our own visions of participation and activism. She presents narratives in a way that begs personal reflection on these histories. Without educating ourselves on the most difficult contours of humanity, we are bound to perpetuate hideous endeavors through the choice to remain naïve.

Carrie Mae Weems, “The Joker, See Faust (Alternate Image)” (2003). Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Paule Anglim.

For more information about the exhibition, visit Gallery Paule Anglim.