Takeshi Murata

Interviewed by Peter Cochrane

This interview has been pulled from SFAQ Print Issue 16.

“Cone Eater” (still), 2003, 4:26. Courtesy Takeshi Murata and Ratio 3, San Francisco.

There is a language created by Takeshi Murata that surfaces in the breakdown between analog and digital media. Artifacts, distortions between transfers, and erratic colors appear, which he uses and manipulates to create a totally new vision. Working between animation, photography, and video, he is invested in the interchange between media. There is also a consistent subtextual critique of American culture and consumerism that is the perfect companion to his dystopian vision. Think ‘80s horror flicks that stem from monsters growing out of sewage or mallrat teenagers who fall under governmental control through drinking too much of an experimental new soda. Or “The Price is Right.”

THE VIDEOS

“Monster Movie,” 2005. 3:55. Courtesy Takeshi Murata and Ratio 3, San Francisco

“Monster Movie”

Both the subject matter of many of the films used for source material and the presentation through the breakdown of imagery—expanded artifacts, interlacing ripped apart, repetition, and alteration of speed—seem to reference dystopia. We are given something recognizable that is then exploded into swirling formlessness. And as soon as we lose ourselves in a mass of color, you launch a monster back into reality. How do you relate to this rapid teetering between seductive abstraction and abrupt horror?

It is about levels of perception. The habits formed looking at things are evolutionary necessities to parse the amounts of visual information coming at us every day. My eyes are all business all day, while my ears get to hang out and chill. It shows. When not working, I can enjoy and understand abstract sound more deeply and immediately. This is much more of a challenge with abstract images. With sound, there is no looking for representation that isn’t there. It can just get absorbed. Unless it’s like a bus honking or bullet firing. With visual art, it’s almost like the brain needs to be fooled. Or extremely relaxed.

With “Monster Movie,” I wanted to connect these two ways of perceiving things into a single shot. I think there’s a fear of losing the connection and comfort with all the things we see every day. Madness can be defined by this. And I guess the horror comes from the knowledge that all our understandings of things are made up, or just arbitrary. Or is this just an American horror? Maybe somewhere else an arbitrary existence wouldn’t be horrific. I don’t know. I should try meditating again.

I was amazed to realize that as you pull apart each repeated clip by the seams, it’s the idea of abstraction that becomes the constant we grow to rely on. Either the colors are maintained (though constantly moving) or the method of change seems to follow an algorithmic pattern. But as the object moves—a monster writhes; a hand cuts through the melting; eyes snap into view and brush away again—it creates a post-clarity wake in this abstract field. I feel like our natural inclination is to think of the figure as a constant, but we can’t grasp it for long enough to create a narrative. As soon as the loop loses all distinction, you switch scenes or bring back a moment of narrative reality, leaving us to start our process of understanding again. Is there importance in seeing the same image over and over until we can no longer recognize it?

Haha! I’m answering these right after reading without reading ahead. You do a better job describing what I’m going for with that video. Looping is another way of breaking down familiar representation. Like repeating a word out loud until only the sound remains.

“Silver”

Have you seen the film “Decasia” (2002) by Bill Morrison? I couldn’t help but think of it when I saw Silver. In his movie, we bear witness to the de- cay of digitally scanned cellulose nitrate film—abandoned by production houses in the 1950s due to its unstable nature and possibility for combustion—as haunting disintegrating memories. Actors melt away into grotesque figures and buildings alight in flame, all created by the physical decomposition of film. But in “Silver,” you are controlling the fracturing of a benign (what appears to be) Hollywood black-and-white scene. A woman taps on a piano key, stretches, and then puts on a necklace. Or so I’m guessing. By the time the camera has panned down to her, you’ve manipulated her gestures to such a degree that she’s become a stream of gray waves atop a synthetic, gurgling soundtrack that matches her languorous movements. What opportunities do you think are provided in digital manipulation that weren’t before the creation of digital technologies, and how does it relate to film?

The similarity is the loss of code. But the interesting thing to me with manipulating the video data was the organic result. Usually digital glitch had very little direct connection to the natural world. At least the old world. And being able to control it added a level of human hand, and intent. More narrative. More warmth.

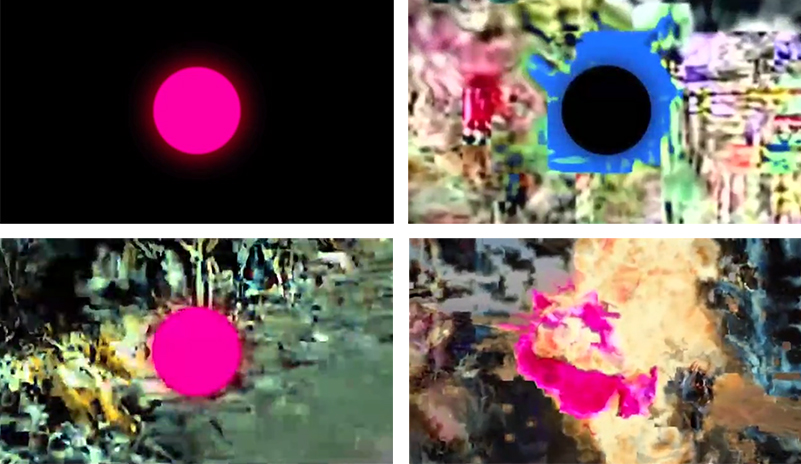

“Untitled (Pink Dot)”

For me, this piece combined many of the concepts I think you’re working with throughout your films. Constancy and change flow simultaneously. We start with a perfect circle, a vibrating hot-pink dot in the middle of a blue field. Each color alternates with black every microsecond. A soundtrack using left/right stereo sound to the fullest pulsates back and forth creating something consistent we come to expect. What looks like the introduction to a trancelike meditation is ripped through by Rambo sliding over a desk before continuing on his rampage of death and destruction. As he, his villains, and his flamethrower all streak into the frame and melt away in paint-like streams, the pink dot continues to flash in the background (except once, when it too dances with Rambo’s inferno). I feel like you are toying with expectation and calamity with a hint of pop culture.

It’s an interest, and angst, stemming from an informed age. Information age? It makes satire one of the best, or the best ways of reconciling this, for me. Otherwise I’m just trying to not think about it. Escapism is an effective route too. How else do people deal with the knowledge of all the shit that’s going on? Rambo is one way.

“Homestead Grays”

“Homestead Grays” holds the most direct audio/visual relationship you have created. Can you talk a bit about your relationship to sound? How do you decide what direction to go with music, and do you co-collaborate? Some works are very ambient and harmonious while others are full of discord. What prompts each?

There is usually a year between most of these, so a lot of it is just the time, and what was going on for me. With “Homestead Grays” I remember wanting to impose limits, or define a rigid structure, in which the work would need to exist. I chose to work in black and white with only hand-drawn looping animation and minimal compositing. The feeling of the work was airy, with a building of action. I asked my friend Ross Goldstein to make the soundtrack because his previous work with field recordings seemed like a good fit. Then I tend to stay out of it. I like seeing what other people will bring to the work. And from video to video, it changes how much direct relationship there is with the visual and sound. Robert Beatty made the sound for a lot of my videos. And Devin Flynn with Plate Tectonics made the sound for “Monster Movie.”

“Infinite Doors,” 2010. 2:04. Courtesy Takeshi Murata and Ratio 3, San Francisco.

“Infinite Doors”

If I had been guessing at your criticism of American consumerist culture up until watching “Infinite Doors,” it was solidified after I heard the announcer from “The Price is Right” squawk prizes one after the next. In the two minutes of the film’s runtime, I counted the word “new” used twenty-eight times, and “car,” the holy grail of prizes on that show, used eight times. The bodacious women introduce free prizes, the doors slide open repeatedly, and the crowd cheers with an insatiable appetite. (As for my favorite unexpected moment, a Nazi enthusiast from the ending of “Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark” melts on one of the new, free flat-screen TVs!) If this is a clear signal of numbing overconsumption, can you talk a bit about how these ideas work into other projects? Do you think that they are heightened in the digital age?

As a child of the ‘80s (mostly), I was one of the targets for commercial marketing on steroids. I didn’t know why I loved “Star Wars” action figures so much, but George Lucas sure did! The ‘80s-era marketing is comical now, and easy to make look ridiculous. With “Infinite Doors,” I wanted to show my affinity for it, for better and worse, and understand how it shaped my aesthetic development. With the digital age, it’s harder to see the humor because it’s harder to see. It’s definitely heightened, or maybe honed is a better word. How else are Facebook and Google worth billions, right?

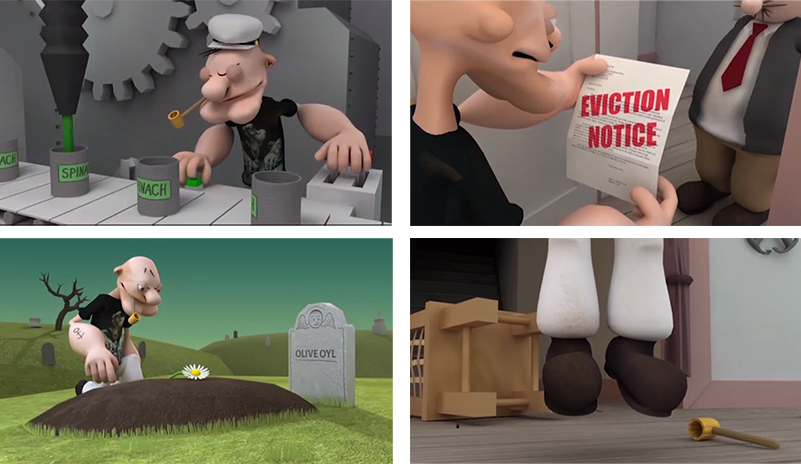

“I, Popeye”

This is a seriously bleak take on an American cultural icon in your first fully 3D-animated video. Here we see a man who has lost it all: Popeye now works at a “spinach” factory (or rather, green goo slopped into labeled spinach cans), he is delivered an eviction notice by Wimpy within the first few seconds, Brutus is on a ventilator in the hospital, Olive Oyl and Swee’pea are dead and buried, and after a spinach-fueled fit of destructive rage at his home, Popeye hangs himself. But this is where his fun begins, as he drives into a trippy postmortem world of bending colors and stimulation overload. We saw him dream of a similar space when he fell asleep earlier at the factory. Is digital art a kind of freedom from the mundane? While I do think of it as an infinite playground, how does it relate to our physical and emotional realities for you?

Art has always had that freedom for me. Including technology in the process makes it even more exciting. With “I, Popeye,” I had been watching all these videos of people at home using CG applications, like I myself was. I wanted to achieve the same directness I saw in these videos. I felt being a novice with the tool could take some of the shine off. You know what I mean? There was no hiding. It felt revealing.

“Night Moves,” 2012. 6:04. Courtesy Takeshi Murata and Ratio 3, San Francisco.

“Night Moves”

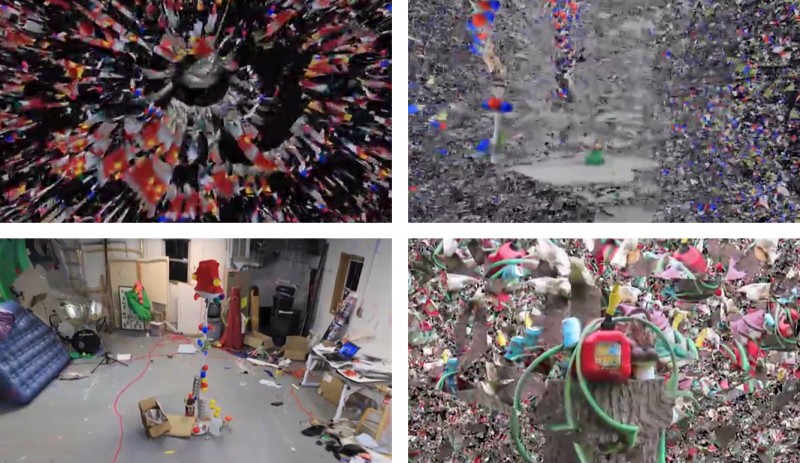

Process is something I can’t stop thinking about with your videos, and the creation of “Night Moves” is totally beyond me. It’s this hybrid of studio recordings, sculptural objects, and kaleidoscopic refractions. Shots are mirrored and overlaid one atop the next: moving, distorting, consuming, destroying then creating. We get a thousand little views of one object, which then refracts infinitely into total static. As if to mock my turning, trying brain, something starts laughing maniacally halfway through. Takeshi, help! What is going on here?

Haha, thanks! This was a really fun video to make. I had about a month before a show at Salon 94, and had been wanting to collaborate with my friend Billy Grant for years. He happened to be free for what we thought would be a week of intense work at my upstate New York studio. It turned into four weeks, and we finished the video days before the opening. We had realized early on that we needed to set up a framework in which to work if we were going to be able to get anything done, though forgot to multiply that by four to be realistic. The framework had to be for both the real and digital world. In the real, we used only the studio as stage, and objects and trash within to make characters. In the digital space, only photogrammetric scanning of all the objects and space, and 100% mirrored planes. We ended up building everything in the day and shooting and animating at night. We worked every day without much sleep at the end, but it was a great experience. There was an immediacy that I like looking back at this one.

“Oneohtrix Point Never”

Here we have this great interaction between the still image and your videos. This film gives us prolonged looks into your highly refined installations and the narratives found within each. I’d like to ask you some about your photography later on, but what was the impetus to create this piece?

I’m a huge fan of Dan’s music, so I jumped at the opportunity to be part of his latest release. The other artists involved were great, and many were friends. The images I used were also produced as prints. I had really wanted to release them back on the screen as well, where they had been made. I like the idea of a still life—a minimally moving music video—and the song was a perfect fit.

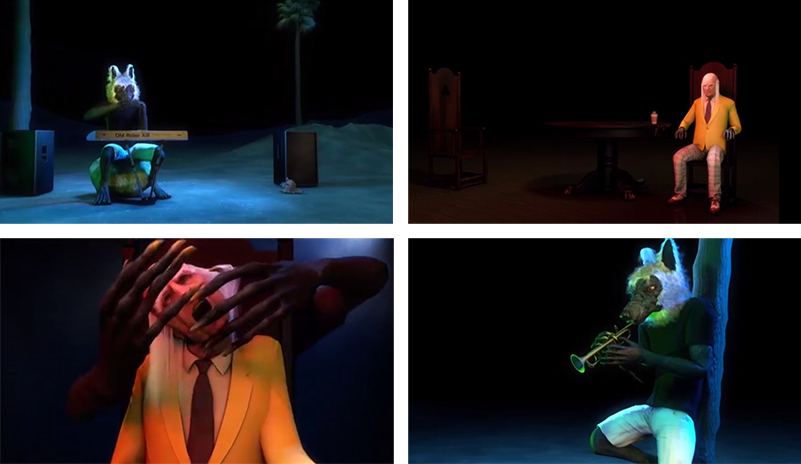

“OM Rider”

Flipping between a synth-playing werewolf in a desert and an old, stringy man sitting in a chair silently sipping coffee from a to-go cup, “OM Rider” presents a strong story. The werewolf eats a fish and vomits, the man throws dice and repeatedly lands snake-eyes. The werewolf jumps on a motorcycle and speeds off into the night, the man stares at a knife lodged in his table. The werewolf gets high. Then, like some long-take Dario Argento shot in “Suspiria,” the camera follows the man up a spiral staircase with only a hint of red light illuminating the scene. The old man cuts a banana, hears the werewolf growl, and gets one look at him in the reflection of his knife before having his head snapped. Slumped over the table, the army’s bugle cry, “Taps,” begins to play. Between “OM Rider” and your photography works in “Synthesizers,” I feel like you’re treading a very different path. The elements are present in each—American pop culture, elements of ‘80s camp and masterpieces, a digital reality created from our own—but now we have tight narratives and 3D animation without artifacts or manipulations. How would you describe “OM Rider” within your previous pieces? Does it represent any major change for you?

A couple years ago I decided I had to teach myself 3D. It’s allowed me to consider much more. Even just adding a 3rd dimension, and thinking in terms of sculpture, film and painting, was a big change. I’m still only beginning to understand the possibilities. The other reason I’ve been interested in the process is that it’s used everywhere in the culture. By using it myself, I feel like I can address things more from the inside. “OM Rider” is my first video going this way. Inside out.

THE PHOTOGRAPHY

“Synthesizers”

The photographs of this series are so elegantly constructed that their fabrication eludes me entirely. The focus on color arrangement and the materiality of the objects is puzzling in an exciting way—are they porce- lain or digitally crafted? Is a camera even involved? Oddly, it isn’t until a video from “Synthesizers,” titled “Street Trash,” that I am able to convince myself that these are digital renderings and not physical fabrications; something in the way a light source warps and briefly moves across a beer can shows the man behind the curtain. Speaking of, “Street Trash” is a sensational video. It is hypnotic. As soon as I lose myself to watching a yellow highlight wrap around a perfect cone to fade into a purple shadow, over and over, this concentrated study of geometry and color, my eye darts back to the lighter, then the Coors Light, and always again to the VHS of “Street Trash,” like some memento of ‘80s despair. How have the films of the ‘80s influenced you?

I’m a huge fan of ‘70s and ‘80s movies. Your earlier reference to Argento was right on, too. And the ‘80s were the Renaissance of schlocky trash horror. They were lawless, lowbrow and cartoonish, and often reflected one human nature perfectly without talking down to the viewer. One of my latest interests has been re-examining these in my own life, and in a different era. I try to avoid nostalgia, but who knows.

I feel like your intentionality with photography is altogether different from that of your films. There is a distinct layering of symbols that can be almost systematically connected to varying histories. Objects link to each other tightly both spatially and ideologically to create a concentrated narrative. How does the still differ from film in potentiality for you?

The narrative of a still image can be less rigid than in moving images. I like that still images can leave the flow of the narrative up to the view. In linear film, you are always guiding the viewer. The smaller area of the movie screen, or lower resolution, makes visual detail much more difficult. So with the still life, I wanted to concentrate on detail and non-linear, non-paced narrative. I found and modeled all kinds of objects that had connections for me, then composed them all at once in several different spaces.

How do you envision the future of digital art? For me it feels limitless, as if artists have just opened Pandora’s Box, even though we are decades in now. Do you think you would be creating work if you had to operate outside of the digital realm?

I think the “digital” distinction in terms of production is almost gone. In many fields— photography, film, and print especially—it’s getting nearly impossible to produce work non-digitally. And, obviously, it is almost impossible to escape culturally. It does feel limitless, for better or worse!

“Art and the Future,” 2011. Pigment print, 23.5 in. x 50 in. Courtesy Takeshi Murata and Salon 94, New York.

For more information, visit Takeshi Murata.