Joan Brown

Gallery Paule Anglim

14 Geary Street, San Francisco, CA 94108

October 8–November 15, 2014

Joan Brown, “The Lovers #2,” 1973. Enamel on canvas. 73 in. x 85 in. Courtesy of Gallery Paule Anglim.

Joan Brown was a restless soul. She was married four times (Brown, Neri, Cook, Hebel), and in the last five years of her life (1985–1990) traveled to Belize, Burma, Egypt, Germany (West and East), Greece, Guatemala, Hong Kong, Israel, Italy, Jordon, Malaysia, Mexico, Singapore, Thailand, Turkey, and finally India, where she succumbed while constructing a commissioned sculpture. She was a Beat Princess (she would have despised and dismissed the appellation); swam from Alcatraz to the mainland; lived fast, died young, and left behind an impressively diverse visual heritage.

Joan Brown, “Adventures of a Woman #2, 1975. Enamel on canvas. 78 1/2 in. x 79 in. Courtesy of Gallery Paule Anglim.

Beat princess? Brown was a San Francisco native, taught by Bay Area Figurationists Bischoff, Oliverira, and Lobdel at the California School of Fine Arts (now SFAI); exhibited at legendary Beat venues (6 Gallery, Batman); lived next to Jay DeFeo and Wally Hedrick during the painting of DeFeo’s The Rose; married noted Bay Area sculptor and fellow student Manuel Neri; counted such disparate artists as Wallace Berman and Bernice Bing as friends; and gained early recognition (a New York exhibition at age 22) resulting in a lifelong teaching post at Berkeley, a Guggenheim fellowship, over sixty solo shows, and inclusion in an equal number of posthumous group exhibitions.

In a video interview conducted by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and available on the Internet, Brown states that, “Success to me is still finding those surprises, and the excitement and challenge of pushing the work just a little further each time to try to dig out the surprise which I haven’t dug out before. And that is to just keep growing and changing and keep letting go, letting go, letting go of any kind of boundaries or rules or regulations that I or anyone else sets up. What I mainly want to be is surprised: the joyousness of that surprise. Going past what you know.”

Joan Brown, “Woman Jumping,” 1974. Oil on canvas. 84 in. x 72 in. Courtesy of Gallery Paule Anglim.

Challenging herself had its costs. Her fluctuations of style bewildered critics and art historians. One critic wrote that, “Brown’s work is charming and professional and as superficial as those suburban vestals who used to swoon over Ravi Shankar.” Marcia Tucker held her up as a key example of “bad painting” in a 1978 New Museum group exhibition. She was derided for work looking like a cross between Pierre Bonnard and Dick Tracy. Rather, she was influenced by the stripped down figuration of Henri Matisse and the naiveté of Henri Rousseau.

Brown worked in series of paintings, and her 1973–1974 abstracted figurative works are especially well represented in the current Gallery Paule Anglim exhibition. These paintings, most notably Woman in Reclining Chair, 1973 and Dark Pink Nude, 1974 converse with Matisse. Later works in the exhibition, Year of the Tiger, 1983 and Summer Solstice, 1982 reflected her affection for portraiture and Rousseau.

Her works of the late 1950s and early 1960s were created in the manner of Bay Area Figuration, with heavily applied impasto texturing. Her latter paintings receive thinner applications of oil yet remain painterly. If one peeks into the office of Paule Anglim, a 1964 work, Noel on Halloween, can be seen to represent her earlier oeuvre. The later works on exhibition reflect a variant style.

Joan Brown, “Woman in Reclining Chair,” 1973. Collage, ink, acrylic, graphite on paper. 36 1/4 in. x 24 in. Courtesy of Gallery Paule Anglim.

Brown did not take well to the criticism the later works received. During the last decade of her life, she turned her attention to public sculpture, many in the form of obelisks. It was during the construction of one on the grounds of her guru Sathya Sai Baba in Puttaparthi, India, that she fell victim to a construction accident in 1990.

Many would say that she had earlier fallen victim to her enthusiasm with the New Age movement, especially her reliance on Jane Robert’s voluminous array of Seth books, with their preoccupations of reincarnation, clairvoyance, therapeutic dreaming, and out-of-body experiences. But in these work, Brown found a measure of comfort and a universality of signs and symbols, which she adapted to her painting.

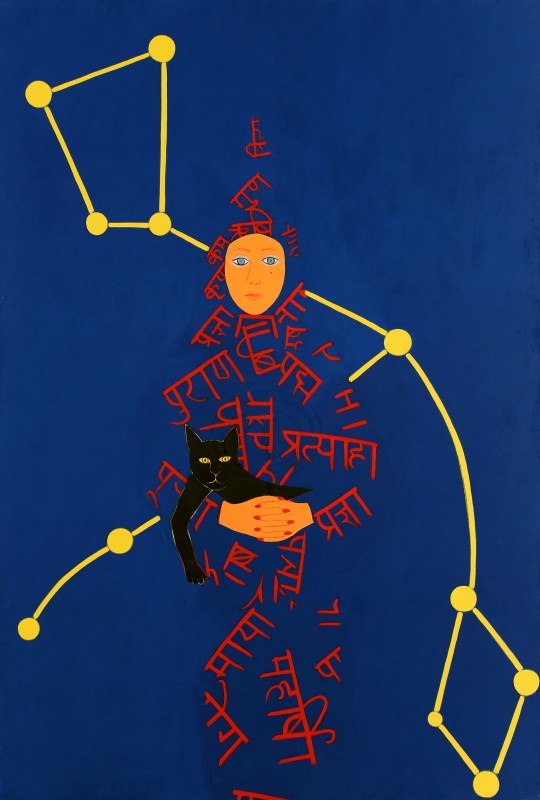

Joan Brown, “Summer Solstice,” 1982. Oil, enamel on canvas. 88 in. x 59 in. Courtesy of Gallery Paule Anglim.

Brown’s is the type of work that goes in and out of style based on the concerns of the era. Acknowledged as a second-generation Bay Area Figurationist, having pushed past abstract expressionism, secures her reputation on one level. Her portraits are as plentiful and revealing as those by Frida Kahlo. The later works are more perplexing but equally rich in layering of thought.

All the artist can do is pursue an inner evolution, wherever it may lead. The work presents a road to freedom, the public catching only glimpses of a work produced in a particular time and place. Eventually the audience’s knowledge of the artist progresses, perspective of the artist’s work comes into focus, and with time, greater understanding of the artist’s vision is attained.

Joan Brown, “The Kiss,” 1976. Oil and enamel on canvas. 96 in. x 78 in. Courtesy of Gallery Paule Anglim.

One era may be captivated by Brown’s earlier impasto paintings. Another time and another place, the viewer may be drawn to the more symbolic works. Reputation in art is a crapshoot—as much to do with audience reception as with the artist. Joan Brown rolled many a dice, and we are only now beginning to learn what numbers are coming up.

Joan Brown, “Year of the Tiger,” 1983. Oil, enamel on canvas. 72 in. x 120 in. Courtesy of Gallery Paule Anglim.