The question, unresolved from part one, remains: how does a developer or a gaming community initiate a folk tradition with video games? By looking at Goat Simulator, one can observe some initial steps towards creating such a tradition by generating development or content through discourse. First developed as a joke, Goat Simulator came into being through community participation and support, purchasing of models from third-party vendors, and the purposefully sloppy implementation of the ragdoll physics of the Unreal 3 engine. The way in which Goat Simulator was conceived and developed provides an interesting account of how game development can be self-reflexive while also creating a space for non-developers to participate in the continued playability of a game long after its release. Because of this openness on the part of Goat Simulator’s lead developer Armin Ibrisagic, the game has fostered an entire sub-community of supporters and enthusiasts to experiment with game development as a “low-stakes” commitment.

This generosity and light-heartedness—driven in part by the tools itself but also the community of contributors and enthusiasts—is the root of the development of a folk tradition within video games. As a result of Ibrisagic’s development efforts the game quickly garnered attention and support from such unlikely sources as the magazine Modern Farmer. In this way, the game becomes more than merely an exercise in technique (albeit purposefully broken) and transcends outside of a cloistered player community. The joke-y quality of this title enabled the game to be considered of greater cultural value or merit than a title that only avid video game players could fully appreciate. Perhaps some of this is due to the absurdity of the gameplay, but some of it must also be attributed to how the game questions the absurdity of simulation games that attempt to present manual labor as leisure (as is the case with the Truck Simulator franchise).

Naturally, a goat breaks through a window in Goat Simulator.

That being said, generating discussion is not the same as generating discourse. The Mordern Farmer mention does signal a departure from insular game journalism, but the discussion does not contribute to discourse regarding contemporary agricultural practices. This is to say that the contribution of the game to the discourse of contemporary agricultural practices is only novelty, and not meaningful exchange. For a game to develop a folk tradition it must avoid novelty.

Although not outright a folk video game, Goat Simulator is tapping into two distinct powerful sources where folk traditions are emerging within video game culture: subversive play and modding. Subversive play is a broadly defined term used to identify communities of experimental play that are using games as they were not intended. The act of subversive play often occurs within small communities of avid players—especially with older video games—and can generate discourse (and peripheral participation) for non-players. One common method that highlights these peculiarities can be found within community speedrun campaigns. These gatherings often showcase an individual player’s prowess and masterful knowledge of a game’s designs, flaws, and engine abnormalities. Exposing these exploits often leads to radical shortcuts for traversing a game without needing to complete time-consuming tasks. This type of subversive play becomes a kind of competition that goes against the original design of the game, repurposing the title into an entirely different kind of challenge.

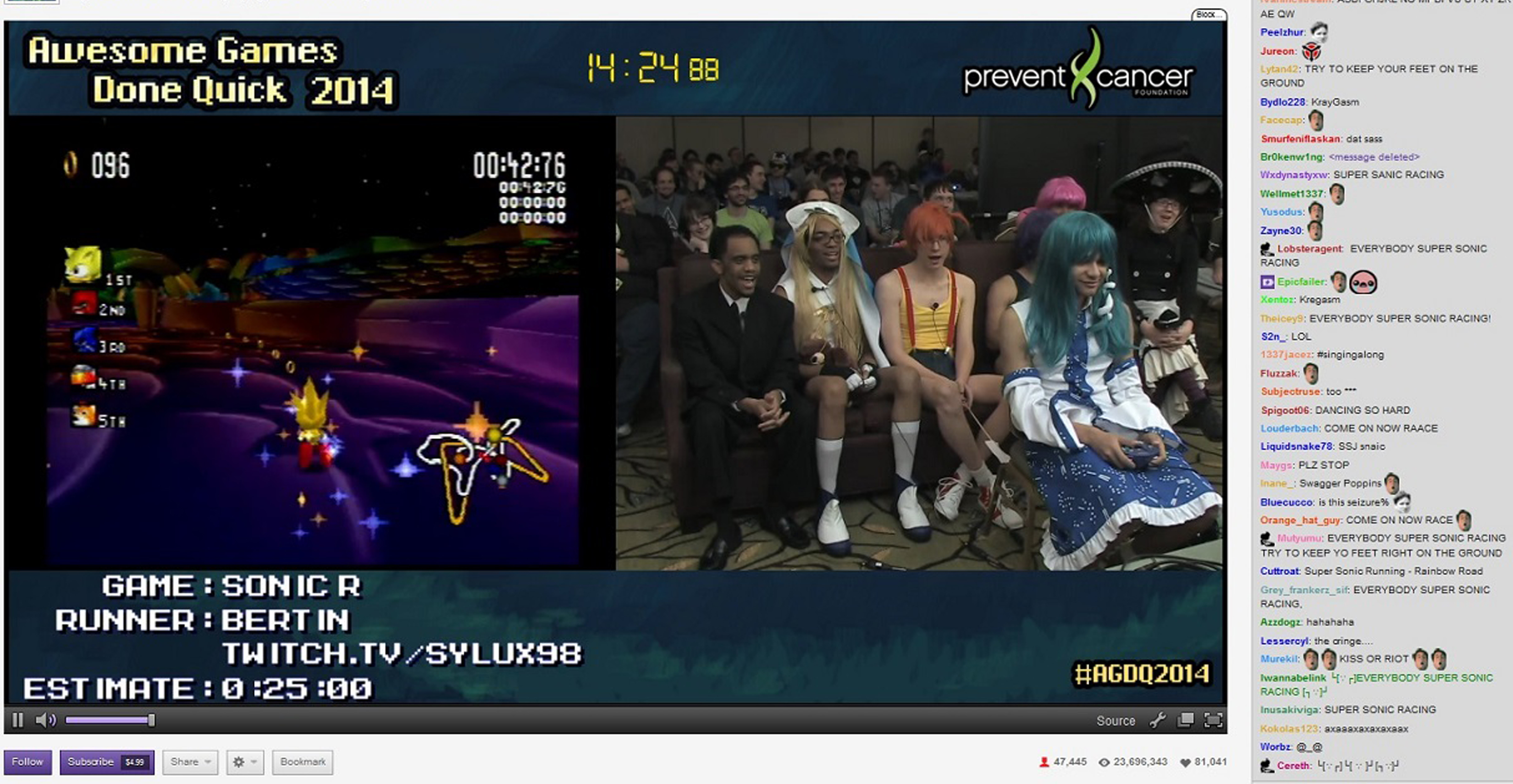

However, the subversiveness of this gesture alone does not generate a folk tradition. Where this style of play starts to take on folk-like characteristics is when speedrun challenges create meaningful exchange outside of the game. Like a fun-run for charities, competitions like Classic Games Done Quick cull together speedrun players to raise money for organizations like the Prevent Cancer Foundation. When the game itself in these speedrun campaigns is merely a wrapper for initiating meaningful discourse via grassroots fundraising, a folk tradition starts to emerge. At this point, the game as playable media transcends being a device for entertainment and is instead used to serve a cause that services a community well beyond video game players. Speedruns that occurred during Classic Games Done Quick repurposed existing older titles and metamorphosed them into folk video games. But this happens only at the point where the subversive gesture of the speedrun creates discourse—or, in this case, benefits—in a cultural community beyond the scope of the players. The speedrun performed in isolation rarely creates discourse, even when documented and distributed though video channels on twitch.tv. Beating A Link to the Past in your parent’s basement will never come close to developing a folk tradition.

A speedrun of Sonic R (developed by Traveller’s Tales, published by Sega, 1997) by Awesome Games Done Quick, 2014. Courtesy of Twitch.tv.

Though Goat Simulator isn’t a speedrun-style game, the somewhat arbitrary scoring mechanism undermines normative gameplay found in standard simulation games. The game itself reinforces the need for subversive play within game development, and underscores the desire of players to experiment within game spaces. However, as noted before, merely presenting subversive play strategies within Goat Simulator does not designate it as a folk video game. In order for Goat Simulator to become a folk video game the gestures of subversiveness would have to generate meaningful discourse outside of gaming culture—instead of only discussing the hilarious potential for broken physics simulation.

It could be argued that one limitation of Goat Simulator is that its intentions are too narrowly defined. Though the game was initially developed with education in mind, the audience never sought to extend beyond or develop discourse with individuals outside of gaming culture. In order to mitigate this, Ibrisagic always intended to release the game with a participatory component for amateur and casual developers. Thus, Goat Simulator points to another location where folk traditions are emerging within video game development: modding. Like many contemporary titles using unique and/or custom engines, Coffee Stain Studios decided to offer players an opportunity to contribute to the further development of the game in gesture of supporting the community that supported the creation of the game from the beginning.

Modders—amateur or semi-pro programmers, 3D modelers, and game developers—take the existing core of a game and modify the content for their own purposes. Several games released on Valve’s Steam distribution platform have dedicated “workshops” where modders can share and distribute content. User-generated content varies from useful head-up display (HUD) changes to the impractical substitution of custom skins to turn your character into popular television characters (think playing Left 4 Dead as a teletubby). Running the gamut of from the helpful to the absurd, mods are a long-standing tradition of player-based contribution to all types of different games. The popularity and impact of modding has generated stand-alone titles, most notably observed in the development of the Defense of the Ancients franchise as a mod for Blizzard’s Warcraft titles. Though limited to PC games, modding exists within a thriving community of player participation that often challenges and/or undermines developer intentions.

Teletubbies mod for Left 4 Dead created by Spartan46. (Note: these are note zombies.)

More recently, modding has becomes a platform for critical reflection that extends and exceeds preliminary game content. As a result, the strength of a game could be measured more on the strength of its modding community/activity than by its initial sales. Modding not only permits player participation, but it also greatly extends the longevity of a game’s impact on gaming culture as well as affords a game more opportunity to initiate discourse outside of gaming culture. The criticality that contemporary modders are bringing to their communities is something Coffee Stain Studios’s observed to be beneficial to their initial development intentions. Ibrisagic and his development team wanted to create a scenario where their initial criticality of simulation games could be carried on by the players of their game. They wanted the joke to live on.

Healthy modding communities like those that exist with Bethesda Studios’ Skyrim shed light on the ways in which players want to create folk traditions within the existing normative structure of blockbuster game development. By noting this, one can argue that folk traditions within video games up until now have only occurred at the point of community activation. The willingness on the part of the user to, for instance, develop a mod for Skyrim which substitutes dragons for Thomas the Tank Engine trains speaks to the energies and desires of players to have titles engage in a conversation outside of games exclusively.

That being said, this example of model (and sound) substitution does not necessarily provide meaningful evidence that modding is the backbone of developing folk traditions within video games. If this were the case, one could argue that folk traditions have existed within video games since the release of Little Big Planet. Though modding is incredibly important for providing users with tools to create a folk tradition within video games, it’s essential to note how these tools get used in order to initiate or foster discourse outside of gaming culture.

![[Left] A dragon and [right] Thomas the Tank Engine massacre a town in Skyrim, developed by Bethesda Game Studios, 2011. “Really Useful Dragons” Thomas the Tank Engine mod by Trainwiz and friends. Courtesy of the Internet.](https://www.sfaq.us/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Skyrim_A-Dragon1.jpg)

[Left] A dragon and [right] Thomas the Tank Engine massacre a town in Skyrim, developed by Bethesda Game Studios, 2011. “Really Useful Dragons” Thomas the Tank Engine mod by Trainwiz and friends. Courtesy of the Internet.

One mod that was released earlier this year for Civilization V by Steam workshop user “Steph” comes very close to establishing a concise model for developing a folk tradition for video games. In the regular mechanic of the game, players can win through a variety of different resolutions between warring populations: diplomatic, dominance, cultural, etc. Steph’s mod offers a new alternative through hosting the World Cup. At a glance, the mod is a way of reaching victory through hosting the premiere event for global fútbol. Similar to a diplomatic victory, the mod initiates a voting process to bid for hosting the world cup within your civilization, but instead of casting votes, your civilization provides production dividends. Once selected, the process of hosting requires substantial building of infrastructural improvements to your cities at an unreasonable building pace. In order to augment this new responsibility a new unique unit is provided (only available through this mod) called the “Migrant Worker.” According to the Steam workshop page:

“The Migrant Worker is half the price of the regular worker and can only be bought. With additional movement, they are willing to work long hours without food or water. You hold their passports and salaries so they’ll never stray—if they run too far from your territory and the heat doesn’t kill them, there are literally countless afflictions and human rights abuses that will! They are the foundation on which your brand new stadiums rest on—or at least their bodies will be. But don’t worry when they perish, with 1.4 million units to choose from, it’s a never-ending supply of cheap labour!”

The mod, in effect, calls for players to consider the political and social weight of their civilization’s quest for victory. By proposing that the metric of winning in Civilization V is without moral consciousness—i.e., a military victory has no refugees or diaspora—this mod provokes players to think of the implications of expanding their empire. Far from the morally devoid creation of a global society based on conquest of one kind or another that the Civilization franchise proposes, this mod puts the political implications of globalism at the forefront of player engagement. As a result, the modder ends her description with the pithy—yet charged—question: “Will you become an armchair activist as well as an armchair general?”

Civilization V, developed by Firaxis Games, 2010. “FIFA World Cup Host” mod created by Steph. Courtesy of the Internet.

By equating the process of hosting the world cup to the activities of a war, the modder suggests that this simulation must consider the cost of dominance and victory in the face of global capitalism and post-colonial theory. This mod situates the player of the game as an active agent of Western-centric logic, culpable in the dispersion of a cultural perspective fraught with unaddressed problematics. By generating a meaningful discourse around the dynamics and political implications of this simulation, Steph’s mod develops a folk tradition within Civilization V.

Though pointing the finger at the seemingly apolitical tendencies of Civilization developer Firaxis (or game development in general), the FIFA World Cup Resolution Mod points to a discourse that appears neglectful, if not downright toxic. Conquest, empires, and creating imperial dominance—popular as they may be—might require more attention to nuance. Thus, the mod itself sheds light on the whole political precariousness of the game’s (unintentionally colonial) stance. In effect, the mod retroactively suggests that the best way to avoid the political culpability of playing Civilization V might be in not playing altogether.

The subversive gesture of Steph’s mod repurposes the game as a mechanism to discuss global politics, and as a result reformulates Civilization V as a site for developing a folk video game tradition. However, in doing so, the subversive gesture renders the game as a playable media—an essential quality for classifying it as a game—somewhat irrelevant for developing a discourse outside of video game culture. This being said, using the game’s modding potential to discuss the ways gaming culture avoids such difficult yet pressing points of discourse, the mod itself acts more as a point of commentary than anything else. Though showing the political pitfalls of Firaxis’s title is a significant folk-like gesture, doing so usurps the gameplay of Civilization V altogether. The gesture, powerful as it may be, becomes a stand-in for play itself. Which begs the question: are video games to be blamed for inconsiderate (or short-sighted) development, or is the way we play these games where we can find fault?

Perhaps the problem for contemporary developers and artists working within video games is not isolated to their medium precisely, but instead can be attribued to the current state of play within contemporary video game culture—or else culture at large. The development practices of contemporary indie and block- buster companies should certainly be questioned, but the problem also requires examination at the point of reception and the ways players and non-players alike demarcate play as an activity isolated from the everyday concerns of society. Though play is essential to the establishment of human civilization (no pun intended here), as articulated by Johan Huizinga, the parameters of play’s existence are perpetually put in opposition (or one step removed) from the rest of civilized cultural expression.

The pervasiveness of video games within popular culture has initiated this process of renegotiation where play lives and how play interfaces (and enhances) other forms of cultural expression. There is a mutual inclusivity between the development of a video game tradition and the breakdown of diverse play spaces. In other words, demarcating the space for play hinges on the development and fostering of folk traditions within video games. Though indie-arcades and game-jam conferences are locations where meaningful discourse is being explored through subversive play and modding, few attempts have been made to cross-pollinate this discourse with non-players.

Recent debates and conversations around #gamersgate, however, have suggested another possible alternative for the development of a folk video game tradition. This is through discourse itself, and not through play and/or gaming. By initiating a debate regarding the ethical imperatives of video games as a cultural platform of exchange—and highlighting the inequities that run rampant in the games industry—the most outspoken voices within #gamersgate are shaping a discourse that should speak to players and non-players alike (and as a result, for better or for worse, is garnering attention from a variety of non-player audiences). #gamersgate poses, aside from its contentious and fraught internal politics, a critical position for analyzing video games and players not through the development of products, but instead through the development of discourse. It is in this proposition that #gamersgate fosters a foundation for a folk tradition within video games.