Chris Ofili

Night and Day

New Museum, 235 Bowery, New York, NY

October 29, 2014 – January 25, 2015

It is a fair certainty that daring artistic choices are the ones worth seeing. The sterile white cube is the most unobtrusive platform for displaying art, and only rarely do curators and gallery directors ever stray from that model. Thankfully, Chris Ofili and the New Museum’s director Massimiliano Gioni and staff have taken the path-less-trodden approach with Ofili’s solo exhibition Night and Day.

Ofili’s work is, by now, a staple in the visual look-book of contemporary art. His mammoth (more on the elephant comparison shortly) canvases strewn with tiny white dots culminating in cutting satirizations of black culture in the guises of religious and pop cultural imagery have been lauded and damned in steady rotation by viewers since his first major showing in Saatchi’s Sensation (1997). A year later, he would go on to win the Turner Prize. Ofili’s participation with David Adjaye for the British Pavilion in the 2003 Venice Biennale only furthered his reputation as an artist with more than just Saatchi’s blessing to his credit. Yet, in spite of a litany of professional accomplishments, Ofili remained a volatile presence in the eyes of the both the British and American public, funneled through works such as his 1998 protest piece No Woman No Cry (an homage to the mother of a slain black teenager), The Holy Virgin Mary (a 1999 work that sparked a lawsuit against its presentation at The Brooklyn Museum by former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani), and a series of rhesus macaque portraits displayed in Tate Modern’s Upper Room (Ofili’s place on the Board of Trustees at the time of its purchase and display in 2005 resulted in a censure from the Charity Commission). These logistical and legal squabbles notwithstanding, Ofili’s work continues to draw audiences inward, balancing intelligent historical engagement with purely entertaining combinations of color and character atop mounds of petrified elephant dung.

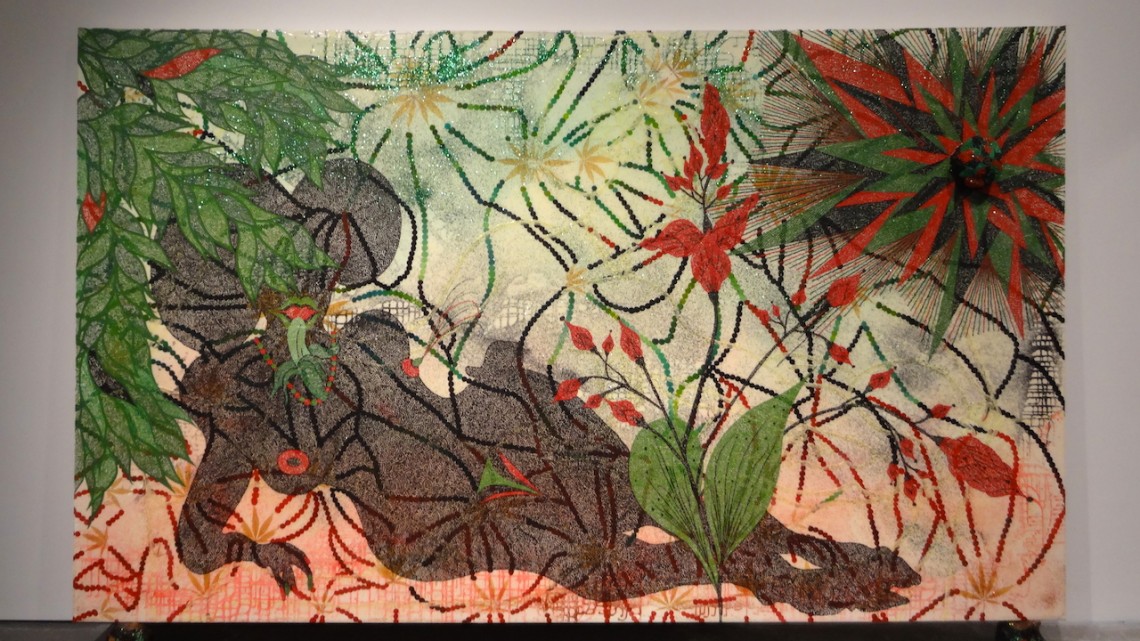

Chris Ofili, “Afronirvana”, 2002 (detail). Oil, acrylic, polyester resin, aluminum foil, glitter, map pins, and elephant dung on canvas,108 × 144 in (274.3 × 365.7 cm). Courtesy The New Museum.

His semi-psychedelic paintings are interlaced with provocative collaged elements, which may allude to deeply personal, conflicted opinions on race and sexuality. Ofili designed the individual galleries within the museum, washed with colors that capably enhanced the viewing experience. This worked particularly well on the fourth floor, where his most recent works were housed. There were immediate associations with Fauvism (I couldn’t help but mumble “Matisse” or “Gauguin” to myself upon stepping inside), both in the paintings and on the wall surfaces, and several wall texts cite specific reference to Black Narcissus (1947), directed by British filmmakers Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Ofili referenced the film’s bold use of color and sexual tension for the architectural backdrop. What could have resulted in an overpowering, imposing palette on the faces of walls was, instead, masterfully darkened with swirls of deep violet and erotic, tropical yellows that felt more like a rich stew in which the figurative works could simmer. Another moody environment in the exhibition, thanks to its painted walls, was a room dedicated to his Blue Rider series, created post-2005. The low, sensuous buzz is similar to that produced by Derek Jarman’s final 1994 masterpiece Blue (title, color, and the film’s melancholy) was entirely applicable, here. Visions of riverside lynchings and makeshift blues bands (reverberations of black American culture) are difficult to make out, at first, in the barely-lit room. This is, again, further proof of Ofili’s prowess as an artist and storyteller: forcing the image to be seen, at close range, but not requiring understanding nor empathy.

Derek Jarman. Still from film, “Blue”. Running time: 79 mins. Courtesy the internet.

It’s difficult to sum up the overall effect of Night and Day. One the one hand, it’s pure entertainment. On the other, it’s a silver bullet into the heart of contemporary art’s body of works revolving around globalized black culture (there is no getting around the fact that Ofili speaks first to those who inherently understand the repercussions of racial, sexual, and cultural exploitation of the African Diaspora). His body of work succeeds in crossing the seemingly impenetrable barrier between rigorous cultural critique and mass engagement. The fact that it is beautiful to look at is a stark reminder of his craft as an artist, regardless of whether or not it is fully understood by his viewers. The New Museum’s vision for presenting Ofili as an artist gracefully and tastefully blurs those lines.

Chris Ofili, Installation Images at the Fourth Floor, The New Museum. Photo Courtesy of The New Museum