David Mitchell

Boundaries

The Dryansky Gallery

2120 Union Street, San Francisco, CA 94123

January 29, 2015 – March 26, 2015

If I can digress from the artist for just a moment and acknowledge the venue in which he is posited, I’d like to welcome the Dryansky Gallery to the Cow Hollow neighborhood, because, in a way, it’s where contemporary art in San Francisco first bloomed, and there hasn’t been much there there in quite a while.

Galleries of Cow Hollow in the 1950s like King Ubu at 3119 Fillmore (1952-1953), 6 Gallery at the same location (1954-1957), East and West Gallery down the street at 3109 Fillmore (1955-1958), Spatsa Gallery on 2192 Filbert (1958-1961), Batman at 2222 Fillmore (1960-1965) and Dilexi at 858 Union for a year (1959) before moving on, set the tone for the San Francisco vanguard scene from the Beat artists (Jess, DeFeo, Hendrix, Bischoff, Martin, et al.) to the next wave of Funk Artists (Conner, Wiley, De Forest, Brown, et al.).

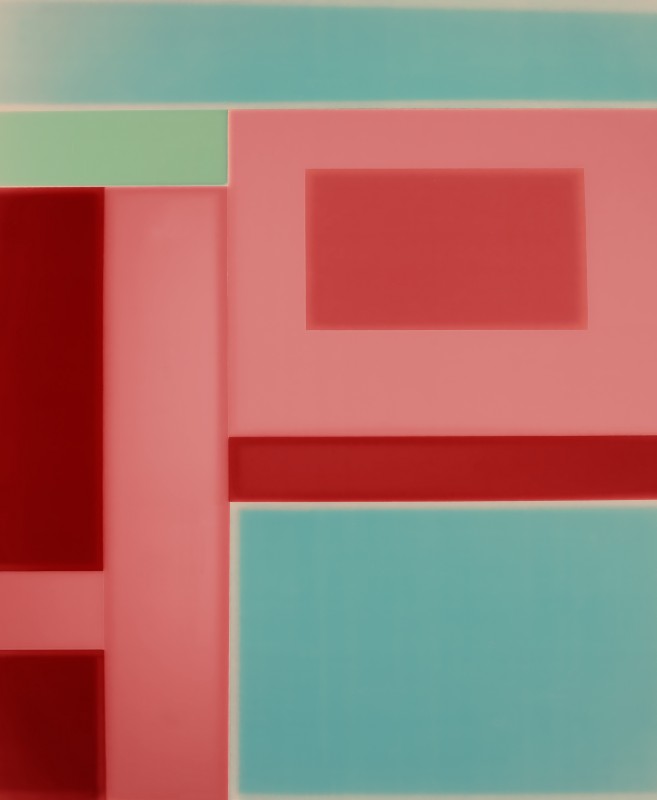

David Mitchell. “AB 200,” 2014. Pigment Print. 48.73 x 40 inches. Edition of 3. Courtesy of The Dryansky Gallery.

Dryanksy’s move to the area amidst the quaint cafés and boutiques of the current Union Street scene is but a faint echo of the past, but it is encouraging that a serious gallery is contending in a scene predominantly fueled by furnishings, fashion and food. The gallery opened last fall. This is their third show. The current exhibition offers much promise of a continuing commitment to serious artists.

David Mitchell was a successful fashion photographer, who was confronted with a life threatening medical condition, and using the tools of his trade, sought to confront it’s reality. The artist’s staunchest champion, Lyle Rexer, author of The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography (Aperture, 2013), writes that the photographs are, “Mitchell’s attempt to find a visual ‘language’ for depicting supremely altered states of perception and consciousness induced by left temporal lobe epilepsy, which first appeared a decade ago.”

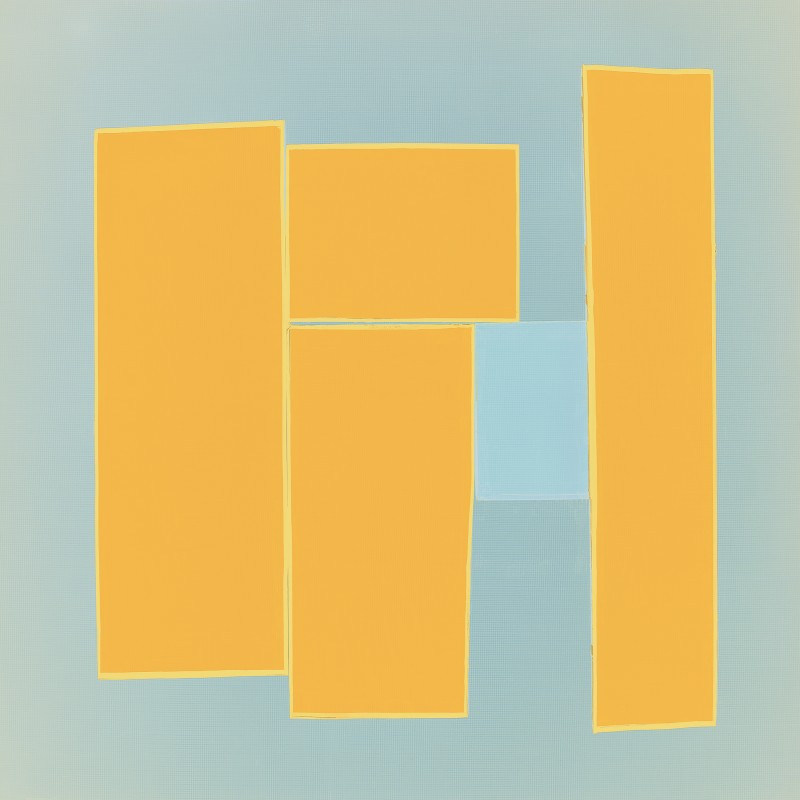

David Mitchell. “AB 202,” 2014. Pigment Print. 49.45 x 40 inches Edition of 3. Courtesy of The Dryansky Gallery.

Mitchell himself states that, “Aside from historic references and comparisons to twentieth century masters, there is a neurological explanation for the preoccupation with form, space and architectural references, the heightened creativity, fervor with which the work develops, and the emotional personal connection to the images which are created in series.”

The British-born photographer, now residing in Southeast Asia, creates photographic works marked by layers of color representing states of perception when overtaken by his medical condition. He began undergoing seizures in 2004, which forced him to give up his commercial career. He turned to fine art photography to better understand and convey his condition.

In a recent interview with SF Weekly, Mitchell explains that, “I can say that epilepsy continues to be relevant in a number of ways. It inspires me to make art in an obsessive compulsive manner—I just can’t stop it. My experiences inform the compositions and the compositions inform the colors. Within the grip of an aura, the sensory distortions can be remarkable.”

With no formal art education, the artist came late to the fine art world. His first foray to an art museum occurred after a visit to England (circa 2010) to the Tate Modern (“First time in an art museum, I am serious”). Encounters with Rothko and Matisse, and later Cezanne, propelled him toward a new course. “I recall turning a corner and there was this painting and it was at that moment that I really understood the necessity for and importance of art. It was a Cézanne. I had at least heard this name by then but had no idea what his work looked like.”

Mitchell’s technique begins with collage and assemblage, which are then photographed and manipulated in the darkroom. “Ephemeral assemblages are chronicled through the lens; however it is the photographic print that is the subject itself and thus—‘the art.’ The conventional notion that photography is about representation is/has been rejected in favor of pure non-objectivity.”

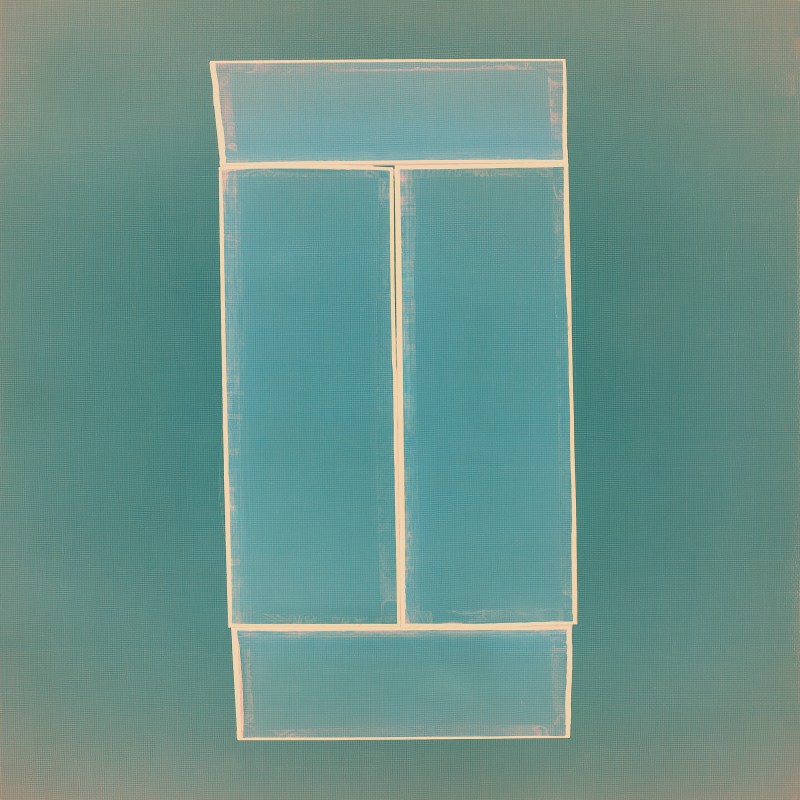

David Mitchell. “AB 101,” 2012. Pigment Print. 32 x 32 inches. Edition of 7. Courtesy of The Dryansky Gallery.

In Rexer’s book, there is a passage about concrete photography, which resonates with the artist. “Concrete photography,” it states, “does not depict the visible (like realistic or documentary photography). It does not represent the non-visible (like staged, depictive photography)… In this way, it abandons its media character and gains object character. It is not a sign of something, but is itself something; it is not what is represented, but what is present; it engenders objects of itself and thus fulfills the central criterion of very concrete art: self-reference.”

His earliest works are blurred, sometimes with transparent tape, recalling the photographic works of Doug and Mike Starn. The latter works have harder edges and are larger. “It was after going to the Tate that I created vertical large scale C-prints in 2013. Rothko’s idea that a viewer should be in the work rather than looking at it resonates with me.”

Being in the work, brings the viewer full circle into the artist’s altered state during the throes of an epileptic episode. There is something compelling about an artist who is determined to come to terms with an ongoing medical condition through his art. It is not art as therapy. It is the creation of a work of art brought upon by an altered vision, expressed to the viewer through years of acquired craft. Nothing could be further from Mitchell’s roots in fashion photography, but the skills obtained over the years in commercial photography are now serving him well in his current studio practice.

David Mitchell. “AB 128,” 2012. Pigment Print. 32 x 32 inches. Edition of 7. Courtesy of the Dryansky Gallery.