Alfredo Jaar

Shadows

February 14 – March 28, 2015

Galerie Lelong

528 W 26th St., New York, NY 10001

Man beobachtet, um zu sehen, was man nicht sähe,

wenn man nicht beobachtet[e].

– Ludwig Wittgenstein [2]

Au fond la Photographie est subversive, non lorsqu’elle effraie,

révulse ou même stigmatise, mais lorsqu’elle est pensive.

– Roland Barthes [3]

—

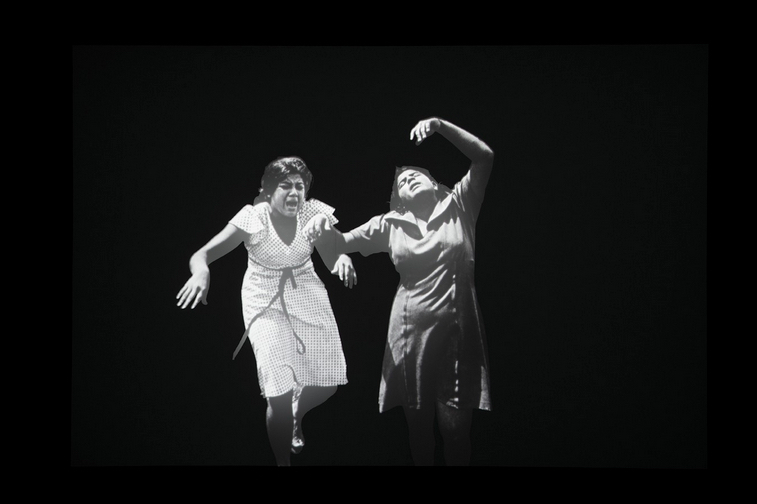

Shadows, an installation conceived by Chilean conceptual artist Alfredo Jaar, explores the power of a single documentary image. On view at Galerie Lelong in New York, the focus of Shadows is a video installation Jaar created from a photograph captured by Dutch photojournalist Koen Wessing (1942-2011) in Estelí, Nicaragua, where he documented the revolution against the oppressive military dictatorship. The black-and-white photograph depicts two women just after learning of their father’s murder—an intensely heartrending scene Jaar called “the most extraordinary image about pain and suffering.” The juxtaposition of dark hallways and lightbox transparencies challenges viewers—sensorially, intellectually, and psychologically—to navigate a labyrinthine space bathed in ghostly white light, which illuminates and sometimes blinds. Shadows presents a paradoxical environment: dense in obscurity yet permeated with clarity.

Alfredo Jaar. “Shadows” Installation View, installation with LED lights, aluminum, video projection, 116 x 174 inches. Original photograph by Koen Wessing (1942-2011): Estelí, Nicaragua, September 1978. Courtesy: Galerie Lelong, New York; © Netherlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam, 2015.

Following The Sound of Silence (2006), Shadows is second in a trilogy of projects through which Jaar explores the ethics and aesthetics of image-making while confronting audiences with fundamental issues of representation. The success of Shadows is two-fold: on one hand, it demonstrates the insufficiency of images to translate a complete and cohesive reality; on the other, it highlights their importance as communicative and didactic tools. In an unlit annex space separate from the rest of the installation, viewers encounter Six Seconds, the final image in Jaar’s seminal Rwanda Project (1994-2000). The lightbox with black-and-white transparency depicts a young girl whose back is towards the viewer. Diffused and unfocused, it appears to have been captured when the subject was in motion. The girl is slightly hunched forward in a tense posture, arms bent at the elbows and held close to her chest, head turned slightly left towards the invisible world beyond the frame. The image effectively identifies the viewer of Shadows as a voyeur—aligned in this sense with the photographer, viewers recognize themselves as foreign observers, outsiders, perceiving the event through a sort of fog, a blurred lens.

Alfredo Jaar, “Six Seconds,” 2000. Lightbox with black and white transparency, 72 x 48 x 6 inches, Edition of 2 + 1 AP. Courtesy: Galerie Lelong, New York

The structure of the installation was inspired by Wessing’s Chili, September 1973—a photographic essay of the military coup d’état in Jaar’s native Chile. Analogous to Chile’s dictatorship, Anastasio Somoza rose to power in Nicaragua with fiscal support from the United States, establishing a violent dynastic regime that stifled the nation from 1936 through 1979. Wessing traveled to Nicaragua in 1978 as tensions culminated between the Somoza regime and the revolutionaries, known as Sandinistas after General Augusto Sandino, who spearheaded the resistance against U.S. occupation and was later executed by Somoza. Wessing spent his time photographing disenfranchised farmers who constituted a substantial portion of the Sandinistas. Shadows employs six of Wessing’s contact prints that are displayed on small lightboxes. A wordless narrative, the sequential images in the installation articulate a bilateral story of personal and national grief.

Alfredo Jaar. “Shadows.” Installation View, lightboxes with black and white transparencies, 12 x 13 inches each. Original photograph by Koen Wessing (1942-2011): Estelí, Nicaragua, September 1978. Courtesy: Galerie Lelong, New York; © Netherlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam, 2015.

Visitors are guided by the light of a black-and-white print down a dark corridor leading to a narrow chamber with two additional lightboxes. Fragments of a story begin to unravel. Visitors then continue down a second dark hallway, which opens to another room, deeper in the recesses of the space. In the second room, a video projection largely covers the expanse of the opposite wall. Frozen in a single image, two women express torment physically—their dramatic yet graceful choreography pronounces a palpable statement of loss and pain. Gradually, the rural landscape that surrounds them fades to black: they are suspended in a dark vacuum. After a few seconds, the photographic details of the women themselves are consumed by a white light: the grey shadows that articulate their features recede as the figures become empty silhouettes. Luminosity intensifies, contrasting strongly with the encompassing black void. As brightness increases, it becomes sharp and blinding. Suddenly, the light from the silhouettes disappears. The theater is swallowed by darkness but the afterimage lingers: burned into one’s eyes, branded on one’s mind. The audience blinks—blind to their surroundings but continuing to see the searing image—and awkwardly fumbles through the space back into the hallway, leading to the installation’s final room with three more lightboxes. The scenes in the third room are set on a domestic stage where friends and family members come together as the devastating reality of the event sets in: an epilogue that buries the story deeply and profoundly in the viewer’s consciousness.

The video provides a violent yet poetic demonstration of the way in which we memorialize situations. Darkness lends the space a contemplative spirituality. An image appears and we identify with it: we engage with the subjects and feel their pain. Parallel to the construction of memory, time and space are negated as we focus on the singularity of this traumatic event. Details dissolve and become pure energy. Our engagement is intensified: the psychological sensation becomes physical when light burns our eyes. Viewers are tangibly transformed by the escalating radiation—the absence of the image is more painful than the image itself. Six Seconds demonstrates the inherent shortcomings of this mechanism. Images allow us to witness an event, but our vision is distorted. Jaar explains: “It is impossible to convey the real-life situation of someone else. Everything that we do as artists, dealing with the reality of the world, is out of focus.”[4] Six Seconds sets the tone for the rest of the exhibit, and speaks to a pivotal moment in Jaar’s life and career. His experience documenting the end of the Rwandan genocide and its aftermath had a profound effect on him: “I felt the tragedy was so enormous that images were incapable of expressing what I needed to express as an artist about the genocide…After Rwanda, my use of photographs has been extremely cautious…exceedingly selective. I think twice before using an image because I lost trust in them.”[5] Throughout Shadows, information is presented visually in black-and-white but without explanation. Though they speak for themselves, the images represent decontextualized moments: individual threads in the fabric of a historical tapestry. The photographic language is universal yet illegible — we can read the words but we cannot understand the vocabulary.

Alfredo Jaar. “Shadows.” Installation View, installation with LED lights, aluminum, video projection, 116 x 174 inches. Original photograph by Koen Wessing (1942-2011): Estelí, Nicaragua, September 1978. Courtesy: Galerie Lelong, New York; © Netherlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam, 2015.

Shadows addresses a paradox in which we find ourselves: we encounter images constantly, but we often do not see them, we are rather blind to them. The artist asserts, “These images are not innocent!”[6] Each image we confront presents an idea, a curated conception of the world—a new “reality” carefully constructed by the image’s producer. Jaar states: “I am suspicious and disillusioned about the uses and misuses of photography in the art world, the press, and the world of entertainment. And to make things more complicated, I don’t think that the general public is well educated regarding images. Generally, we are taught how to read, but we are not taught how to look.”[7] Thus, Shadows is an exercise in learning how to view images, how to concentrate—this is, Jaar affirms, where the essence of our nature exists: “The capacity of our humanity resides in our ability to read an image and identify with another human being. Only in that capacity of focusing…is where the process of empathy and identification can occur.”[8] It is in the obscurity of Shadows that we find clarity. Through blindness, we begin to see.

—

[1] (“The image is a consciousness,” from article title.) Jean-Paul Sartre, L’Imaginaire [The Imaginary] (1940).

[2] One observes in order to see what one would not see if one did not observe. – Ludwig Wittgenstein, Bemerkungen uber die Farben [Remarks on Colour]

[3] Ultimately, Photography is subversive not when it frightens, repeals, or even stigmatizes, but when it is pensive, when it thinks. -Roland Barthes, La chambre claire: Note sur la photographie [Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography]

[4] Alfredo Jaar, in conversation with David Levi Strauss, March 12, 2015.

[5] Alfredo Jaar and Pirkko Siitari, “‘I need to understand the world before acting in the world:’ Pirkko Siitari in Conversation with Alfredo Jaar,” in Tonight No Poetry Will Serve (Helsinki: Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, 2015), 71.

[6] Alfredo Jaar, in conversation with David Levi Strauss, March 12, 2015.

[7] Alfredo Jaar and Patricia C. Phillips, “The Aesthetics of Witnessing: A Conversation with Alfredo Jaar,” Art Journal, Vol. 64, No. 3 (Fall, 2005), 20.

[8] Alfredo Jaar, in conversation with David Levi Strauss, March 12, 2015.