Much of Internet culture uncritically frolics in an ecology greatly affected by the unique opportunities and affordances of the Internet and the web while ignoring the boundaries and limitations that come with it. Many artists and users adopt exciting emergent traits with little consideration of negative or unseen consequences. Artists and technologists seeking to understand and engage with the specific qualities of networked media—be it on the Internet, a Local Area Network, or a meshnet—open up a much needed dialogue about our agency as viewers and users within these spheres, the technical and aesthetic limitations and opportunities, and the embedded politics of these spaces.

If the artists using these networks do so uncritically, they are in fact relinquishing aesthetic and conceptual control over their work to private companies, proprietary hardware and software, and governmental agencies. In this way much of net art, or art using the Internet as its primary means of dissemination, or the more nebulous post-Internet art, are responding to the widespread adoption and influence of networked society and can be critiqued for the degree of control they demand or give away to the network and all of the intersecting influences therein.

Deciphering and confronting these networked spheres of influence is necessary, and some of the most critically and conceptually exciting works today are doing just that. There are already two important and growing conversations around these issues: The first is Stacktivism, from the likes of Benjamin Bratton and Keller Easterling, a movement attempting to confront the interlaced infrastructures and systems—both natural and manmade—that are constantly in dialogue with one another. The other is Critical Engineering, a term coined by Julian Oliver, Gordan Savičič, and Danja Vasiliev to differentiate between new media art that uses technology and makes aesthetic commentary on society, and new media art that directly and critically engages society through tools, interventions, and products, rather than through art.

I’d like to propose another critical framework that I will call Network Critical Media (NCM)—media that critically, experientially, and authentically confronts the network on which it relies. NCM understands that networked communication contains exciting and unique opportunities as well as dangerous risks, and both should be thoroughly researched, explored, and exposed. To understand NCM, we first have to understand the site-specificity of the network, which is vastly complex. NCM continues in the lineage of Critical Engineering and Stacktivism, but also of institutional critique, stemming from the 1960s with the likes of Fred Wilson and Andrea Fraser as a way to critique the embedded politics of arts institutions where the works existed. NCM, like institutional critique and Critical Engineering, contains a realistic optimism; that through more critical engagement we can make the tools and institutions affecting our lives serve us better than they do now.

In evaluating an NCM work, we must ask to what degree the work is in conscious and meaningful dialogue with the complexities of the network it’s reliant on for its creation, dissemination, and experience. This of course requires an understanding that the work has a multiplicity of realities, as the network’s effects move unevenly throughout the connected audience. When taken off the network, the NCM work becomes a hollow artifact, merely a representation of the complexities it was once inextricably linked with. For clarity, I believe that all networked media is affected by at least these five traits, of which NCM must be aware and in dialogue with:

- The physical infrastructure of the network (Internet, mesh networks, LAN) the work utilizes and is accessed through.

- The institutions (Google, NSA, Facebook, Comcast) facilitating and simultaneously affecting (through software, law, policy) the aesthetic, experiential, and power relationships between the work and its viewers.

- The software through which we connect that is the user interface between infrastructure, institutions, technology, and us. Software is full of affordances and biases, largely in service to the institutions implementing it.

- The hardware (iPhone, MacBook Pro, dumb phone) with which the viewer connects to the work.

- The audience as a community that becomes connected to each other and the work, all of whom are affected by #1–3 to varying degrees based on access, education, race, sex, local laws, language, et cetera.

- You, as the viewer, and your experience of #1–4 as instigated by the work.

Critically engaging with many or hopefully all of these traits is what makes an NCM. So while stunning net art like, Cloaque by Carlos Sáez and Claudia Maté uses the unique qualities of the network and platform, it does so uncritically of the network (the Internet) or platform (Tumblr) on which it relies. Furthermore, Ingrid Burrington’s work on exposing networked infrastructure, which will be featured in her forthcoming book, Networks of New York: An Internet Infrastructure Field Guide, has been instrumental to my thinking about networks and is an inspiration for this piece, but does not directly use the networks as commentary. Both of these works are wonderful and important when talking about the Internet or about net art, but neither are examples of NCM, nor did they try to be.

Examples of NCM:

Nick Briz’s, Apple Computers (2013) and “How to / Why Leave Facebook” (2014) are perfect examples of NCM in that he directly engages with the technology, the users, the hardware, and the company involved in his art practice. Briz unearths the embedded politics of Apple’s designs and Facebook’s algorithms, and places his community as well as the viewer at an impasse; we want to use these products, but also expect and deserve the freedom to create whatever we wish with those products.

The genius of Apple Computers as an NCM work is how Briz places the finite product (an Apple computer) as being not a static tool but rather in constant dialogue with Apple through the network. Therefore, while the machine one purchases may be ideal, you remain subject to a shifting politics of Apple; through the network your computer never becomes your own.

Just as many institutional critique artworks were made within the institutions they sought to critique, NCM artists are reaching beyond the art world to be in dialogue with the actors of the network. This is why Trevor Paglen and Creative Time Reports released his NSA photographs under a Creative Commons copyright license and with The Intercept—to help bring the critique of the media beyond the white walls, into the public sphere, and thus in more direct engagement with the institutions the work was critiquing.

Trevor Paglen, Circles, 2015. Video. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist, Altman Siegel (San Francisco), Metro Pictures (New York), and Galerie Thomas Zander (Cologne).

Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev’s PRISM: The Beacon Frame (2013) also uses the network, the hardware, the viewer, the physical site, the people connected, the laws, and the powerful institutions on these networks with us as integral to the piece. Through interactive sculpture, PRISM: The Beacon Frame sought to provide a physical manifestation of the growing discussion around surveillance in a post-Snowden world. Using surveillance tactics now known to be commonly deployed by the likes of the U.K. and U.S., PRISM: The Beacon Frame places the viewer squarely inside the issue by implicating them in only the tip of this surveillance millions are subjected to without warrant.

Interestingly, this piece became a more effective NCM work due to the unforeseen actions of Transmediale staff removing the work from display and threatening to report the artists to the German Federal Police. The extreme irony that artists were unable to exhibit a work not nearly as invasive as the tools in daily use against millions of citizens in democratic nations only pushed the importance of the debate further.

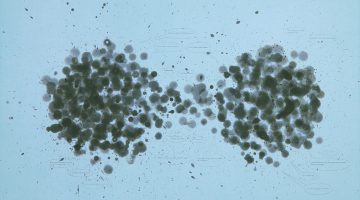

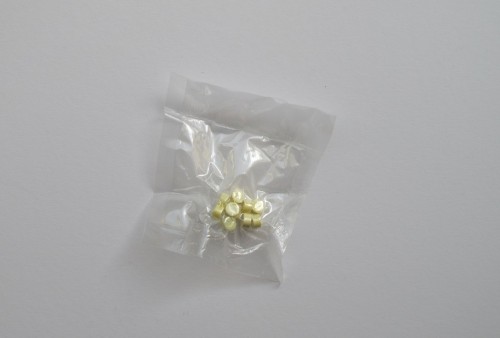

!Mediengruppe Bitnik is a very exciting group for more directly engaging with institutions of networked power. Recently, the group created Random Darknet Shopper (2014), which is an automated bot that, with a weekly bitcoin budget of $100, randomly purchases goods from darknet marketplace Agora. Shown at Kunst Halle St. Gallen, the bot ordered the random items purchased to be delivered to the gallery, which then were displayed.

The day after the three months of the exhibition, the local police seized the entire exhibition due to the purchase of several ecstasy pills. The following litigation resulted in the return of the bot and all other purchases to the artists with no charges issued, deeming the artwork as a protected form of speech. As debates about anonymity software, the growing role of algorithms in our daily lives, and issues of culpability in networked spheres continue, the Random Darknet Shopper is by no means a purely aesthetic or hollow gesture.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik, Random Darknet Shopper (purchase), 2014.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik, Random Darknet Shopper (purchase), 2014.

As the tools for life’s production increasingly come online, they should fall within the purview of the artist as well. As media increasingly connects us together, maybe artists are finally positioned to meaningfully and critically engage in the production of daily life. They should not shirk away from trying, continually relegating themselves to the sterile white cubes of the art world’s galleries. While artists are adopting new technologies and making visually stunning works, the lack of criticality when adopting new tools is worrisome—these networked spaces matter and the best artists will use them and treat them with critical and serious care.