William Pope.L

Trinket

March 20–June 28, 2015

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

250 South Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90012

On view now until June 28 at the Geffen Contemporary gallery of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art (LA MOCA) are the works of Chicago-based artist William Pope.L. Titled Trinket, Pope.L’s exhibition uses a mixture of visual metaphors to address aspects of the American experience, ranging from its long-standing racial disparities to the dynamic nature of its evolving democracy. Viewed in the wake of the events of Ferguson, New York, and now Baltimore (just to name a few), Trinket belies the meaning of its title, rather, offering up images and memories that may seem meaningless in their ubiquity within the American landscape, utilizing them instead to highlight larger, deeper wounds that the nation has yet to address and resolve.

As his largest and most ambitious exhibition yet, Pope.L’s Trinket fills the entirety of the Geffen Contemporary space with large-scale installations, video projections, and performance structures. At the center of the space is Trinket (2008/15), a 54 by 16 foot American flag set into motion by four industrial-grade special effects fans. Trinket is not only the central piece of the exhibit, but the symbolic heart of the argument Pope.L seeks to produce. Originally unveiled during the 2008 presidential campaign, Trinket takes on a new meaning within the context of an unfolding struggle for black rights in contemporary America.

Installation view, “Trinket,” William Pope.L at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles, now on view through June 28, 2015. Photo by Brian Forrest. Courtesy of MOCA.

Much like Pope.L’s earlier sculptural pieces such as A Vessel in a Vessel in a Vessel and So On (2007), a piece consisting of a pirate lady mannequin with a bust of Martin Luther King Jr, turned upside-down, dripping chocolate, Trinket is a monumental construction that seeks to dissolve an idea that is constructed as monumental. As Martin Luther King is often conceived as the father of the Civil Rights Movement, a savior for the nation, and martyr for a greater cause, the American flag is equally imbued with lofty ideals of freedom, struggle, and the stalwart stance for democracy. However, Pope.L envisions these as fallible, innate to the humanity and reality around which we have constructed a protective monumental edifice. “This project,” as Pope.L described, “is a chance for people to feel the flag. People need to feel their democracy, not just hear words about it. For me, democracy is active, not passive. With Trinket, I am showing something that’s always been true. The American flag is not a toy. It’s not tame. It’s bright, loud, bristling and alive.”[i] And as America is torn and tattered by racial inequality and violence, so too is Pope.L’s colossal flag, caught in a losing battle against the forces of the deafening wind generated by the industrial fans. Imperfect, greedy, self-serving, the flag, too, has a 51st star that appears awkwardly sewn against the lower edge of the blue-and-white canton. Much like how Americans often hide the personal imperfections and extra-marital affairs of the heroic King, Pope.L’s flag bears the evidence of an illegitimate child.

Installation view, “Trinket,” William Pope.L at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles, now on view through June 28, 2015. Photo by Brian Forrest. Courtesy of MOCA.

Continuing on the theme of breaking-down the monumental notions of nation (and the concepts that define it), Pope.L offers the viewer Polis or the Garden or Human Nature in Action (2008/2015), an installation piece consisting of thousands of onions, all painted in a variety of colors evocative of flags. The onions, either placed neatly atop a series of tables placed in a grid-like fashion, or found in piles collected in corners around the gallery space, are all within a state of natural decay. As onions, they emit a slight sulfuric smell and some even collect roaming flies. Like Trinket, the active decomposition of Polis is a reflection on the slow but assured demise of the state, of systems that we have come to see as sturdy. By the same token, Pope.L’s video installation Small Cup (2008) depicts a flimsy, dome-like structure slathered in peanut butter (representative of the US capitol building) being hastily eaten and destroyed by hungry goats and frantic chickens. The message here is clear: nothing is sacred and everything crumbles in time (and in the most anticlimactic way).

William Pope.L, “Polis or The Garden or Human Nature in Action,” 2006. Onions, paint. Photo by Thierry Bal. Image courtesy of the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery.

Similarly suggestive of earlier pieces by Pope.L, most notably Curtain (2013), a wall “painted” with ketchup, or Map of the World (2002), a map of the United States made out of hot dog links, Polis and Small Cup can also be seen as meditations on the connection between cheap staple foods and the black experience in America. Using such foods to construct his works, Pope.L calls out the nature of what builds the everyday life of poorer black communities. Like lines on a map, these foods demarcate the pervasive nature of a systematized racism and continued segregation that affect black lives in America. Pulling these foods from his own memories of growing up within this environment, Pope.L now uses them to call out what he still sees as the material relation between what one eats and the politics of a society defined by inequality.

William Pope.L, “Reenactor” (2012). Video still. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

Bringing all of these disparate elements of nationhood, race, identity and poverty together is Pope.L’s Reenactor (2009/15). Spanning four-and-a-half hours and projected throughout the space of the Geffen Contemporary, Reenactor is an absurdist non-story of happenings, wandering through scenes populated by people (often black) dressed as the Civil War-era Confederate Army general Robert E. Lee. Somewhat comic in appearance, the video shifts between instances of everyday events (where those dressed as Lee sit down to eat barbeque or shop for groceries) and more surreal moments (where the players are seen bleeding or exchanging and eating human organs). All of this is played out upon the backdrop of American southern communities (namely suburban Tennessee and the historically all-black Tennessee State University campus) or on mock-battlefields of Civil War reenactor events held in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

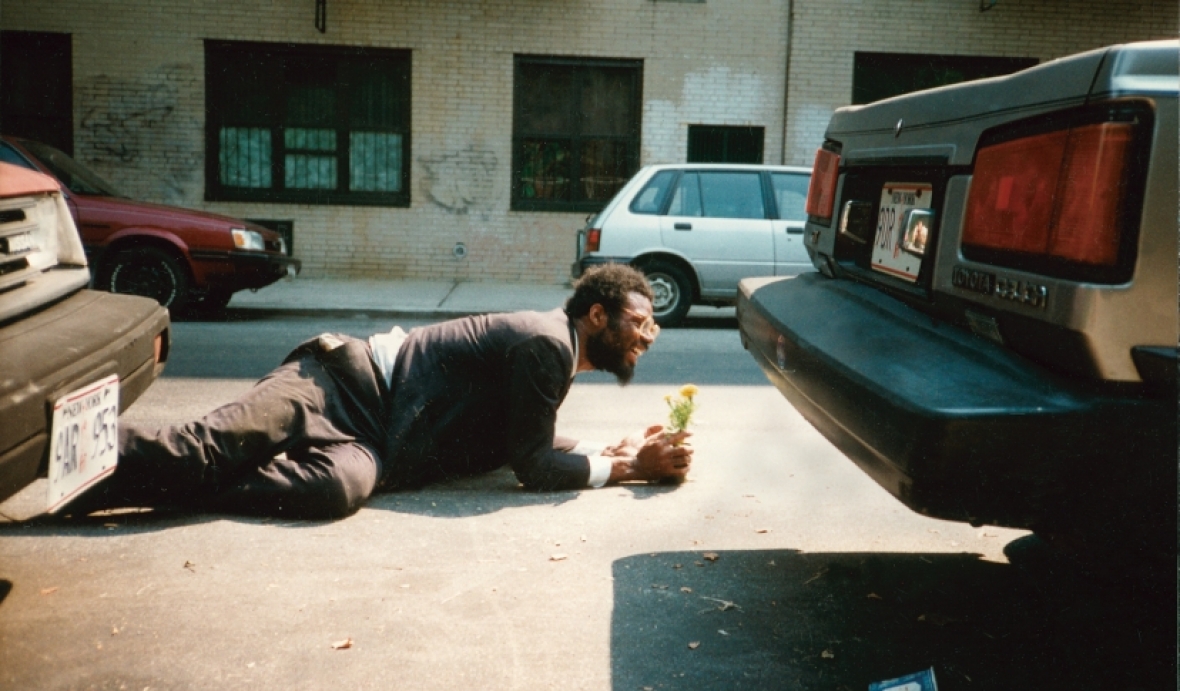

William Pope L., Still from “How Much is that Nigger in the Window a.k.a. Tompkins Square Crawl.” Courtesy of the internet.

Much like Pope.L has done with his now famous Crawl series (in which he first debuted in the early 1990s dressed as a businessman who crawled in the gutters on his stomach throughout the predominantly poor, black communities of New York) or ATM Piece (1997) (featuring the artist “chained” by links of sausages and dressed only in a skirt made of dollar bills handing-out money to passers-by), Reenactor creates instances of visual juxtapositions of racialized expectations and roles played. In these pieces, Pope.L calls out notions of identity that have, historically, pigeon-holed black communities, contrasting these to archetypal constructs that represent wealth, power, and whiteness. The space between these can seem comical at first, but through performativity, the humor begins to vibrate alongside Pope.L’s more serious discourse of how black people are perceived and conceived by audiences. The “strangeness” of a black individual dressed as Robert E. Lee against the backdrop of the pastime of historical reenactment is, for Pope.L, a means to expose the trauma left behind by slavery and segregation. This is the same intentional “strangeness” that was evoked in Langston Hughes’ poem Comes the Colored Hour, which puts blacks in the role of plantation-owners and whites as their servants. Both work in contrast to the notions of the exotic and rawness that white critics have historically attributed to black artists such as Jazz musicians or now to Rap lyricists. For Pope.L, it is with these persistent and destructive notions that he crafts his art.

In Trinket, William Pope.L takes on the myths of American democracy. Reducing the ideology down to their material underpinnings (a flag, the architecture of an American monument, military uniforms), he unravels each until they are left in tatters. Through the humorous intervention of an otherwise patriotic gesture (by the monumentalizing of the massive, violently flapping flag of Trinket) the exhibition is a biting critique of a nation unable to come to terms with its ghosts. The self-described “the friendliest black artist in America,” Pope.L uses a mixture of humor, re-appropriated symbolism, and the stereotypes that seek to neutralize the black American, as his weapons to address and unmask these ghosts.[ii] Within the sterilized confines of the Geffen Contemporary, his practice seems isolated from the context of the real world they take on. His video works, his surreal performances, which have always been at the heart of Pope.L’s practice, however, firmly reinforces the relevance of the artist’s work in the complex and problematic landscape of modern America. This is perhaps suggestive of the underlying tension between Pope.L’s art as object and as constructed argument in that they resist institutional categorization. Instead, like the nation he seeks to critique, they are dynamic, reflective of an ongoing struggle against the marginalization and neutralization of the black experience in America.

[i] “MOCA Presents William Pope L: Trinket,” last modified March, 30, 2015, http://sites.moca.org/the-curve/2015/03/30/moca-presents-william-pope-l-trinket/.

[ii] This is the name title the artist uses to refer to himself. It was also the name of a publication in conjunction with a 2005 retrospective of Pope L’s work (Mark H. C. Bessire, William Pope.L: The Friendliest Black Artist in America (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002).