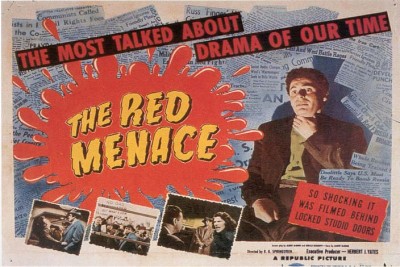

Following World War II, the Red Menace mentality held a death grip over U.S. foreign policy. In the 1950s it fomented U.S.-backed clandestine coups, by the ‘60s covert and not-so-covert interventionism, and by the ‘80s it had become full-blown state policy. This posture was predicated upon something called the domino theory. The domino theory argued that if one nation or people came under the influence of communism that the surrounding countries or people would succumb as in a toppling domino effect—that the cancer of socialism, that “enemy of democracy and freedom” would spread. Today this alarmist tendency has transcended rhetoric to become a logic in and of itself. It has gone beyond the limits of the Cold War and been applied to undocumented immigrants, Muslims targeted as part of the War on Terror, the spread of crime and the rise in criminality, gangs, and drug use. But here’s the kicker: the domino theory isn’t wrong and it’s the global im/migration crisis that proves it.

If it isn’t Africans flooding the streets of Italy, Spain, and France, it’s Eastern Europeans and former Soviets flooding into Germany and the U.K. In Asia and the Persian Gulf, it’s mass populations flooding one nation or another stemming from Bangladesh, China, Pakistan, or India. In the Americas, Haitians move into the Dominican Republic, Trinidad, Tobago, and the Bahamas; Guyanese move into Brazil and Venezuela; Central Americans enter Mexico and the U.S. In every continent of the world, there is a looming fear of the “foreign horde” overburdening and taxing the system to the breaking point. In most of these cases, these are seen as narrow problems to be handled by the individuated state. They don’t see these population movements as bound to a global phenomenon intimately tied to neoliberal economics, environmental crises, imperialist wars, and the related capital/resource exploitation. In many cases these diasporas are deeply rooted in class and racialized populations encounter an antipathy of the migrant that has descended into outright and brutal xenophobic violence. This interethnic and intra-national predation is used as a mechanism to further strengthen the narrative of these dangerous, uncivilized hordes—a way of reminiscing—that all too easily throws itself back to ancient Roman citizens’ pleading about the barbarians at the gates!

In 2000, North African protestors living in the Spanish region of Almería clashed with police who had been systematically harassing and brutalizing them, while politicians and collaborators called for the largely Moroccan masses in dissent “to behave like civilized people, containing your rage and ire.” In 2002, as Brazil’s economic future began to turn, the porous border between Guyana and Brazil inverted from the “illegal immigration” of Brazilians going into Guyana in the ‘90s to Guyanese moving into Brazil and Venezuela, a trend that continues today, resulting in the socially conscious leftist governments of Venezuela and Brazil militarizing their own borders as a preventative measure to the development of yet another oppressed underclass with no options or mobility. In 2005, residents of the North African ghettos in Paris and Marseille, to name but two cities, rioted in the streets in response to decades of state-sanctioned marginalization and oppression. Similar riots emerged the same year in Australia, in waves of racialized anti-immigrant violence targeting largely identifiably Muslim and Arab populations in Cronulla; counter-violence ensued resulting in mass arrests and brutality. In 2010, Africans in Rosarno, Italy rose up in response to ongoing harassment and violence at the hands of the Italian police, and a racist Calabrese infrastructure that wants cheap labor but has kept them living in tent cities and dormitories. In 2011, in reaction to rioting and mass protests in response to the impact of the 2008 global economic crisis and austerity measures, some Greeks began shifting their rioting and physical violence onto Pakistani and Afghani immigrants, sparking counter-riots against a state that failed to act, or many times seemed to condone such violence. In 2012, Ethiopians in Hatikva, Israel fell under attack in successive waves of race rioting and violence by Israelis of European or Ashkenazi origin.

In 2013, in a spat of staggering self-denial and internalized racism in line with their tradition of Antihaitianismo, the high court of the Dominican Republic issued an order that began a project that continues today of mass deportation of Haitians, with many Dominicans justifying their support of the states policy through their age old-slogan “I’m not Black, I’m Dominican.” Many of those deported, however, were Dominicans of Haitian origin—in other words they were monolingual Spanish speakers who didn’t understand Creole or French, making them culturally disabled newcomers upon deportation to a country they’d never known.

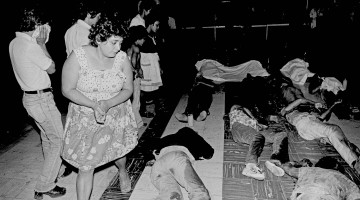

Manmade and natural disasters have made Haitians into refugees across the hemisphere, arriving at each nation’s doorstep in such numbers that specialized policies and community hostility have now become the new nativist norm. Similar to the situation faced by Palestinians in the Middle East, Haitians have become the underemployed, bottom rung underclass worker that is viewed as a burden on the societies that they had no decision of joining. Last year, in Trinidad and Tobago, popular anti-immigrant violence gave way to a new policy in which the state openly blamed immigrants for all the violent crime and gang activity on the islands, and began a registration and deportation process targeting Haitian and Jamaican immigrants. A similar policy was enacted in the Bahamas that targeted the same two groups with the addition of Cuban immigrants added to the deportation lists, concluding in the same result as the Dominican Republic—the deportation and incarceration of legal residents and citizens of external origin. In February of this year, 10,000 people took to the streets of Port-au-Prince in protest against the ongoing mistreatment of their countrymen still in the Dominican Republic. This was a direct response to the lynching of Haitian Henry Claude Jean, whose body was found hanging in the town square of the Dominican Republic’s second largest city, Santiago de los Caballeros, only to then have the investigators very quickly turn around and claim that “he was killed by other Haitians.” This protest, like so many others, was symptomatic of the growing discontent in Haiti and of similar protests worldwide in which pro-immigrant and anti-immigrant forces clashed over a situation in which both sides are the victims of economic policies that have impoverished everyone.

Protests in Port-au-Prince, February 2015.

Though these waves of violence have simultaneously been referred to as hate crimes, race riots, and anti-immigrant violence/counter-violence, uprisings, etc., the conflation, confusion, and failure of terms to correctly describe what is going on is in direct relationship with the inability of an evermore interlocking globalized world to contend with the very domino effects of its own creation. The growth of incendiary and xenophobic anti-immigrant tendencies have reached such a fever pitch and become so ubiquitous that it has even birthed a resurgent fascism and hard rightward shifts in places like Germany, France, Greece, and even Northern and Eastern Europe—places that were traditionally antifascist leftist strongholds, which have become enclaves of contemporary fascism. Global anti-immigrant hysteria and economic necessity has fostered the creation of permanently mobile migrant populations (or “problems”) trapped in an intercontinental cycle of immigration musical chairs.

Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras have descended into states of instability of such gross proportions that the last close approximation is each country’s respective periods of civil war. Honduras, the original Banana Republic, has converted into a nation of easily exploitable labor and natural resources and has played a full-fledged role in proxy wars as a client-state to the U.S., and, what in the ‘80s was then called the “USS Honduras,” has become a nation-state-sized drug mule made out of terra firma, beholden to U.S. interests while utterly indifferent to the needs of the Honduran domestic population. This trickle up scenario has created a flood of economic and social refugees. While numerous “south of the border” countries have begun the anti-black policy of deporting Haitians back into a country whose infrastructure was reduced to ruin, the “Central American problem” emerges at the U.S. border in the form of passing the buck.

In May of 2014, the reality of catch-and-release detention centers in the southwest U.S. came into vivid detail on television as hundreds of “illegal immigrants” were dropped off at a Greyhound bus station in Phoenix, Arizona after being processed and released from overwhelmed detention centers in Texas. The state of Texas and various regional administrations of ICE and Homeland Security tagged and released the recently detained with a court order in hand mandating they report to Immigration and Naturalization in 15 days. Abandoned in cities they had no connection to or contacts in, families consisting primarily of single mothers and small children found themselves bused to Reno, Salt Lake City, Phoenix, Tucson, Los Angeles, and San Diego and simply expelled into the streets. The numbers were so large that what had previously been an undercover practice of deportation became public scandal—but scandal would imply it was or is dealt with, when it hasn’t been at all. The practice still continues. Previously, various detention centers would offload their human excess on another state, county, or facility, making it “their problem,” with anonymity and complete impunity. Christian charities and organizations provided for the immediate needs of people abandoned to a system that sees them as a statistical nuisance. Within hours waves of donated money, translation, transportation, communications, and legal services, food, clothing, temporary shelter, toiletries, and children’s care products found their way into the hands of church volunteers, many of whom worked without sleep for nearly a week just trying to get hold over the crisis.

Migrants, consisting of mostly women and children, disembark from a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) bus at a Greyhound bus station in Phoenix, Arizona May 29, 2014. Photograph by Samantha Sais.

Suddenly the faces of half-starved, parentless children, young women, and single mothers, all of whom were the victims of some kind of sexual or physical violence en route to the U.S., began to appear in the news cycle. Children sleeping like caged animals, piled one upon the other in detention centers, filthy and huddled together under space blankets. The scary part is that it’s unclear what’s better: to be temporarily housed in a detention and processing center modeled after a penitentiary that at least has regular meals and some semblance of stability; or to sleep on cots laid out in community centers and churches, dropped in an utterly alien city that is radically different from the intended destination of immigration. They left their homes for the possibility of something safer only to be passed off as human refuse in a never-ending cycle.

But the U.S. wasn’t alone. The global immigration system had become a human warehousing operation camouflaged by a distracting shell game. Places like Gibraltar passed on surplus migrants to Portugal, Spain, Italy, and France. Similarly, construction laborers, predominantly from places like Bangladesh, Yemen, and Somalia, would be deported just before it was time to pay them for the work they had provided, or with their special work dispensations and visas expired, then cast into the streets of the Middle East, totally ignored as if they hadn’t been contracted by companies in Egypt or Gulf states to rebuild cityscapes.

This is the domino effect. The real crisis is manmade and it is about humans. These are the ones that have been abandoned by the effects of capitalism. They are the orphans of a history that ignores them. They are the victims of a system that denies them but upon whose backs it has been made. One is left to wonder the question never asked: why immigrate in the first place?

*Correction: Part Two of “The Hidden Story in the U.S. Immigration Debate” was left without subtitle in issue 19 of SFAQ. The subtitle of Part Two is: “Journeys from and to a Destination Nation.”