White Ladies of the Canyon

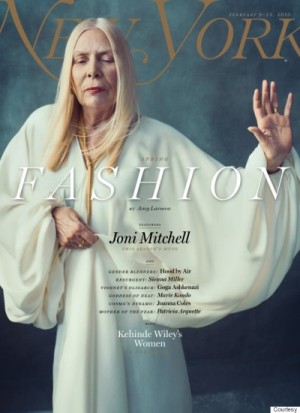

In February, Joni Mitchell told New York Magazine that she has an affinity for black men. In fact, she went on, she really understands what it’s like to be a black man because she wore blackface a few times in the ’70s, including on one of her record covers. It was a revelation of gross racism I’d have rather not heard.

Joni Mitchell means a lot to me. I first heard Ladies of the Canyon on a dubbed cassette in my friend Lucia’s bedroom in high school in the mid-’90s. Sunlight was streaming into her room at a sharp diagonal, and Joni Mitchell’s voice was streaming in multidirectional curves, like ribbons that were at once totally substantial and floating on air. I wanted to crawl into the mood of that music and stay a while.

I’ve needed to surround myself in Joni Mitchell moods many times over the years since. Sometimes it’s the bright-scrubbed joy of “Chelsea Morning” when I’m making breakfast or putting flowers on my table early on a Sunday, and lots of times it’s when I’m emotionally overwhelmed. Afraid or grasping or hurt in a way that I’m starting to tighten, or shrink, I’ll put on Blue or Court and Spark or Clouds and sing with her for an hour and something will shift. Instead of tight or small, I’ll start to feel open, fluid. Brave instead of afraid. In awe of uncertainty like I’m in love with it. (How beautiful, suddenly and again, that we really don’t know life at all.) Mostly, I’ll feel no longer insecure about being but thoroughly grateful to be a woman with a lot of feelings. And some nights in that particular mood it has seemed to me that anyone who doesn’t appreciate Joni Mitchell’s music is a misogynist, anti-emotion and especially anti the ways women express it.

Joni Mitchell has never been someone I look to for tight feminist theory—my love of her work has always been more emotional than political—so I wouldn’t be surprised to hear her say some weird essentialist stuff about men and women, and wouldn’t expect her to give New York a considered statement about racial justice or anticapitalism. But damn, blackface?

Grrrl Punk Colonizer: Never Violence!?

I’m studying German, and my current reading level in that language is children’s books. So, among other things, I decided to revisit Pippi Longstocking—a childhood favorite I’ve already revisited once, as a riot-grrrl-ish teenager who loved not only Pippi’s mismatched thigh-highs but all of her unapologetic weirdness, embrace of her own nonconventional beauty, and total disregard for the established orders of her world. I’ve loved the playfulness of her subversion.

But a few pages into my recent re-reading, I encountered Pippi’s fantasy that her lost-at-sea pirate father had shipwrecked on a South Seas island and, whoa, was now ruling over the indigenous population. This is presented as a light, and even inevitable, childish fantasy of a missing papa’s well-being.

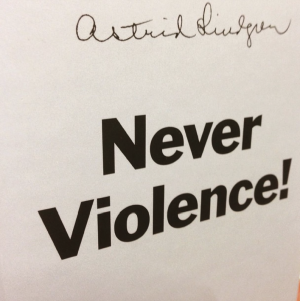

The day after I read this, The New York Review of Books posted an image on their Instagram feed in which the words “Never Violence!” are signed by Pippi’s creator, Astrid Lindgren. I commented with the question that had been in my mind since the night before: does the “subplot of [Pippi’s] papa as a South Seas king ruling over indigenous people on an island he is washed up on . . . ever get anti-colonial?” @nyrbooks responded by posting a link to a blog entry in which Astrid Lindgren’s daughter insists that the Pippi books reflect the colonial racist stereotypes of their time but are meant as critiques, rather than endorsements, of them. I don’t know.

I do know that I, a white American, read the Pippi books as a child and as a teenager and managed to not really notice the “South Seas king” bit. It seems hard to imagine that a Pacific Islander child reader would have had the same experience.

The Limits of Woolf’s Oceans

Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is my favorite book. Short but vast, it reveals the inner lives of an array of characters from childhood into old age. Their lives unfold parallel to the sun’s rise and set and the tide’s ebb and flow in one day on one sliver of beach, and are as staggeringly ordinary and amazing as those cycles. Woolf’s sentences are long and winding and yet perfectly constructed, representing the layered, refracted, shifting interiors of her characters’ minds. She articulates human perception and feeling intimately, individually, and as these individual streams intersect and bleed into one another, the language flows and interweaves like lives do. While radically expanding the boundaries of the novel with stream of consciousness, shifting points of view, and attention to language and perception over plot, in this book Woolf also radically expanded our capacity to perceive and describe human consciousness.

Woolf’s mind was not small. She was one of the key shapers of modernism in English literature. Part of her innovation was novels told from multiple points of view—and not only multiple, but quite different: she was capable of imagining and writing the depths of characters of different genders, ages, and personality types. She was bisexual, and believed that some degree of duality around sexuality was necessary for a writer to imagine, or inhabit, characters of different genders.

And yet her perspective was grossly limited in relation to race and class. Woolf was a wealthy white British woman in a time shaped by colonialism. While she was horrified by the injustices of war and patriarchy, and pushed against false borders of gender and sexuality, she understood “independence” largely in terms of control of wealth, and her novels are marred by occasional descriptions of “gipsies” and “natives” that uncritically reiterate racist colonial stereotypes.

As someone who has struggled with intense moods and a sense of alienation (like Woolf did), who thinks and feels in words, who experiences life mostly at the level of the subtle internal perception—quiet on the surface but churning underneath—I find in Woolf’s work a resonance, a way of reckoning with reality that seems more true and more relatable than much of what is found in “the canon.”

Woolf’s mind was capacious and complicated, critical and creative in a million directions. She pushed against the canon, irrevocably illuminating in A Room of One’s Own not only that and how women had been shut out of it, but also the huge unknown corridors of human experience women writers might have lit. Woolf cracked open space for women and experimentalists that changed literature and our understandings of life itself.

And yet in novels that were on most levels extremely carefully considered, she simplistically, thoughtlessly, and harmfully repeated stupid racist stereotypes.

So What?

It’s the basic concept of intersectionality, a term coined by black feminist Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1989: all systems of oppression are interconnected, and some people’s lived experiences involve multiple and inextricable identity positions in relation to those systems. A black lesbian cannot separate her blackness from her womanhood, or her lesbianness from her blackness, and so forth. And just because someone experiences one form of oppression does not mean she is not oppressing other people in other ways. The idea that white women or white gay men are non-oppressive, or “get it,” because one aspect of their identity (gender, sexual orientation) is subject to systematic oppression or marginalization is, well . . . there’s a whole (continuing) history of white feminist racism, and a present of white-gay-male colonialism, giving evidence to the lie of all that.

It’s not surprising that individual white people’s minds—no matter how broad, beautiful, or creative some aspects of those minds— have internalized racism. The whole social context feeds it to us, surrounds us in it, helps us not question it. That individual artists I happen to love are vulnerable to that is not surprising in the least. And though a revelation like Joni Mitchell’s racism is always disappointing and makes my love of the art she makes a lot more complicated, it doesn’t stop me from loving it altogether.

Over the last several decades, a yarn has been spun by a few loud, big-gun white-dude artists (Philip Roth, Norman Mailer, and co.) that feminism and post-colonial critique is “political correctness” that aims to deny artists their right to honestly represent “reality.” Contrary to all their wounded-misogynist whining, critique is not censorship. But it can be a force of expansion. Yearnings for justice and freedom are not what limits art. What is limiting is violent power relations. What narrows an artist’s creative possibilities a lot more than the specter of “PC” is the warping logic and narratives that uphold social hierarchies.

Privileged people internalize these logics and narratives, and our lived experiences rarely provoke us to question them. And so we rarely do question them because to do so is to be morally annihilated until you crawl through that muck and learn some new ways to see and to live. The more privileged the gaze, the more fitted to norms, the less expansive the view. Let’s not censor but simply undo the colonial cowboy story. It’s not the conqueror who gets to the plateau and really takes in the whole landscape. He’s too focused on his own rapacious agenda, and too new to the place to catch most of what’s going on. It’s the people who know the land and each other and also are having to keep an eye on the movements of this threatening character that can really see the landscape, from wherever they’re looking, even or perhaps especially if their vantage is on the periphery.

It feels not that interesting or useful to ask whether we should or shouldn’t still like or enjoy or otherwise appreciate work by artists whose worldviews are polluted by the violent social systems that shape our world. I don’t care if you like Annie Hall, and I don’t think it’s very helpful to wring our hands about what it means to like Annie Hall even while believing Woody Allen is a child abuser and gaslighter. Though I do think our respective experiences with different forms of violence affect how easily we are able to overlook signs and representations of them in order to appreciate other aspects of a work of art, and conversely how hard it is to see anything else in a piece of art that reflects the worldview that has done our own person harm.

Whether one likes a thing is not that interesting or important. It matters a lot more to think about how art is informed by and perpetuates a worldview that does violence.

And if we are going to get anxious about what antiracist or feminist or other justice-minded critique might do to art, worrying that this kind of critique might censor or otherwise limit artistic imagination or the creative process, I’d ask: How are artists’ and viewers’/listeners’/readers’ imaginations and creative potential limited by internalization of oppressive narratives and norms? Where is the real constriction and distortion coming from? How does this affect the work? How does it affect the possibility of art to alter or expand our perceptions and understandings of basic realities of human existence? What if artists’ imaginations were unhindered by the massive distortions of white supremacy and colonialism? And what would looking at art look like if all our gazes were free?