From the Singular to the Indexical in Contemporary Portraiture

For the past 14 years Paul Mpagi Sepuya has lived in New York and worked as a photographer whose focus was pinned tightly on portraiture. Not only did Sepuya think of his photos as portraits, he was, in the beginning, serious about shooting “straightforward” portraiture, as in taking a singular image of a person as a way of, at least within that moment, fully capturing their exterior and even their identity. However, unlike other portraitists, Sepuya found himself returning over and over again to the same subjects at different points in their lives. Not only that, but his process seemed as much based on happenstance as it did on investigation. He would rarely organize a shoot or a sitting within a particular place, but instead would randomly run into people he hadn’t seen in a while and arrange for a shoot on the spot. In this way, a fluidity that is not very characteristic of much portraiture seeped more and more into Sepuya’s practice, until it eventually became clear that to take one picture of one person and present it as conclusive was not only false but futile.

It proved far more intriguing and generative to begin to cultivate an ongoing lexicon or index of sorts through which many lingering stories and personal narratives might or might not reveal themselves over time. His practice, at least conceptually, drastically shifted from singular images to an ever-developing, meandering string of recurrent faces, interiors and objects that one, if they paid close enough attention, could read like a novel.

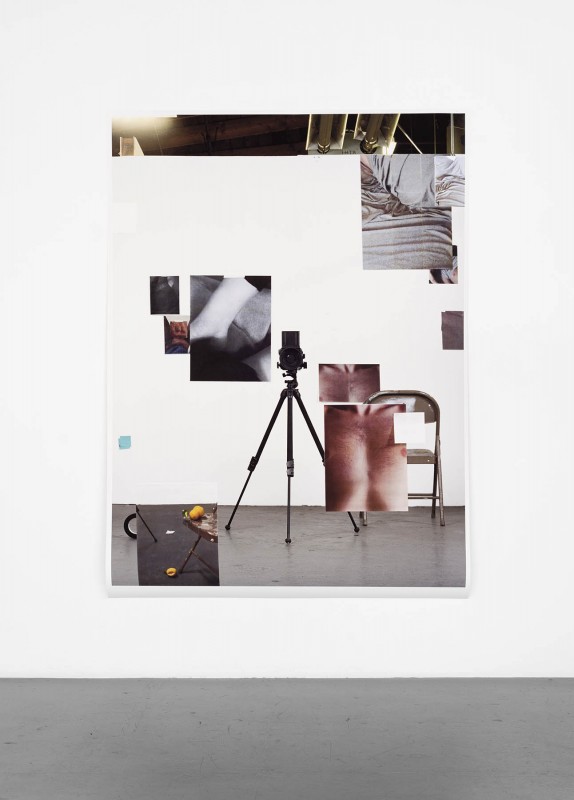

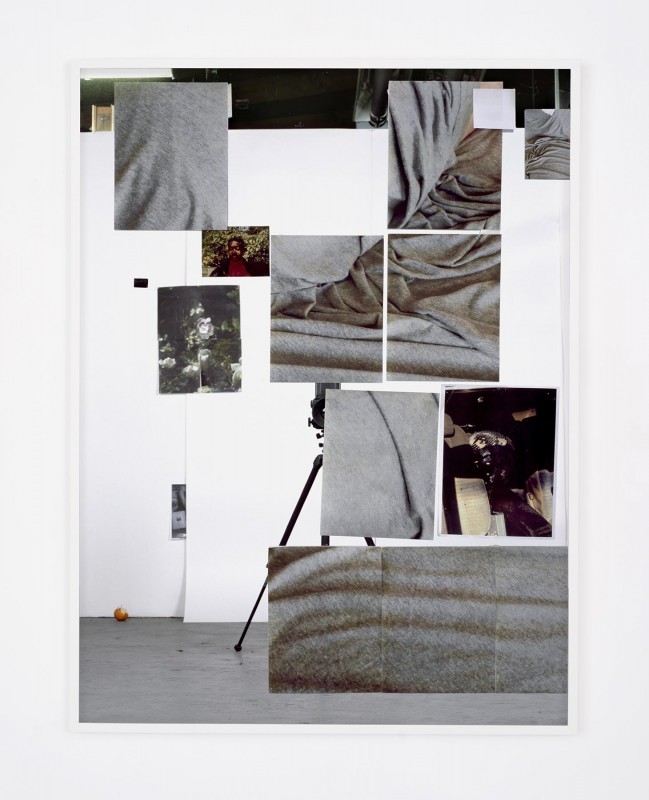

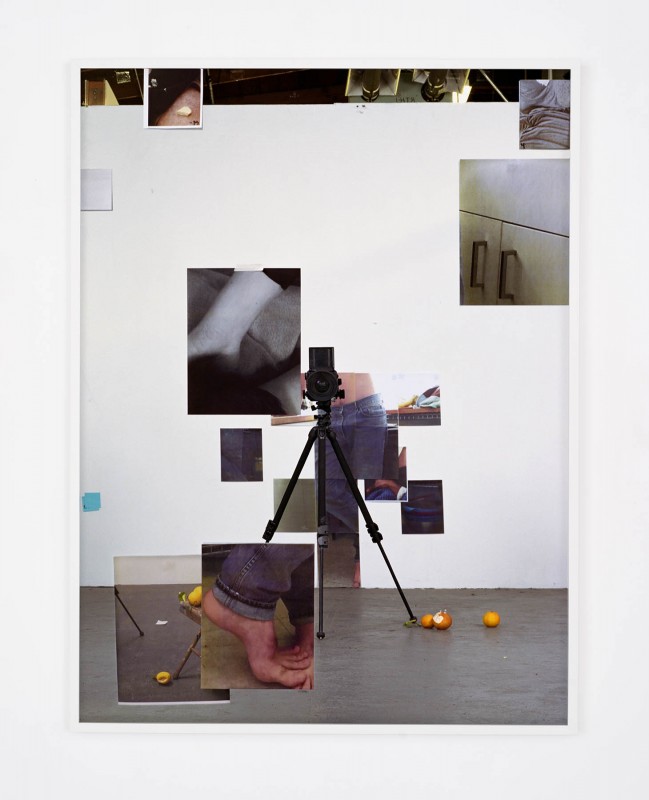

Another, more recent shift, has been Sepuya’s move from New York to Los Angeles in 2014 to begin graduate school at UCLA, where he currently lives and works. As school often does, this time (and the critiquing eyes and viewpoints of his fellow classmates) has allowed Sepuya to look at the massive body of work that he has produced over the past decade from a newly macro perspective. This, he says, has allowed him to see, and begin to respond to, the varying degrees of legibility that run throughout his work as it spans many of the layers of subtext, which have either purposely or inadvertently been inserted into his photographic archive of people and places as their image recurs over time. It has also taken much of the daily bumping-into-a-subject type of process out of his current ways of working, as L.A. unlike New York, rarely yields these kinds of coincidences. Instead, Sepuya has found a renewed significance for the studio space, where he returns to older material and configures new images from fragments, some of which have formed the works that are now on view at DOCUMENT gallery in Chicago in his most recent solo exhibition, aptly titled, Figures/Grounds/Studies.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Study for T.H. with Five Figures, 2013 – 05 (0702), 2015, installation view

Figures/Grounds/Studies, DOCUMENT, Chicago, 2015

Courtney Malick: We spoke a lot about the different/overlapping trajectories and narratives that you continue to follow as you photograph and re-photograph many of your subjects over long periods of time. Can you say a bit more about the organizational process that goes into this on the studio and shooting side and conversely on the editing and exhibition side?

Paul M. Sepuya: When it comes to organizing the narratives and pictures, there are both concurrent and overlapping streams. First, there are the ongoing photographs and related material that I’m making and accumulating within a personally driven portrait practice that follow my friendships and relationships, and then there are the more contained projects like STUDIO WORK, SOME RECENT PICTURES / a journal., or the recent Figures / Grounds / Studies that develop within their own timeline and get “pinched off” so-to-speak from the larger stream.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Studio, March 12, 2014

So you don’t often think in terms of separate bodies of work. Would you say that your work is in some ways one continuous project?

That is true to an extent. Specific projects tend to be defined and framed by exhibition opportunities more than anything else. The underlying content does not change, so many subjects repeat in multiple or reiterated instances that produce different outcomes in different but related projects. My day jobs have always been in arts administration and I love organization, so my source (RAW) files and my negatives are filed by year and then by subject or location. In the physical space of my studio, everything is allowed to wander. I love creative ah-ha moments when things accidentally find themselves in conjunction and conversation.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Study for D.A. with Three Figures (0905), 2015.

I see! With organization in mind, I am curious to know if you can explain the ways that various literary works have influenced your imbricated form of portraiture?

Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet is probably the best example of that influence in terms of structure, due to his shifting subjective point-perspective across the four novels of that set. I’m interested in the ideas of genre, what each needs from the author and what each asks of the reader in contextualizing content. Journals, letters, memoirs, autobiography and poetry—Durrell plays with these translations of one genre into another to organize the narrative of his main character and that character’s relationship to the beloved who haunts him. I also think of Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West, Christopher Isherwood and Truman Capote, Patti Smith, and Patricia Morrisroe.

Wow! That is an amazing connection to make. With narrative in mind, can you tell me if there are any particular stories that are unfolding within the works on view at Document?

I am aware of making works where the sum total of content lies outside of the conversation about art. It’s better served by gossip and friendship, and that’s a productive and dynamic place for me to be.

So then how close to life, do such installations as what’s on view at Document, for example, come?

On the record, I don’t think I’ve ever described a work as illustrating a specific personal narrative of mine, but if you know me there’s a lot you can pick up.

Would you say that this kind of “story” or portrait of a story, is one with layers that allow for differing vantage points based on one’s familiarity with your practice overall?

I think that’s pretty spot-on, thinking about different vantage points based on one’s familiarity with my practice, but also with the day-to-day that falls outside of “art.”

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Devin, 2008

At first glance, these works seem to be documents, in that they are happenstance shots capturing real people that are a part of your life, photographed within their natural environments, or within a natural relationship to one another. However, I am wondering if it’s possible to read these images of faces, personal items, interiors, etc. as stand-ins or representations of a different, symbolic set of characters or actants that convey a broader meaning?

I do think of the images as constituting figures. These figures can be understood as fragments of the subjects that they are inspired by, but still appear bigger than those subjects. The figures are never disconnected from me or from their subjects, but they do become representations of my desire, which is constructed around the subject. And this relational dynamic, in turn, creates in itself a new character.

Hmm… Can you explain this with regard to a particular piece?

For example, Theodore and the representation of my desire for Theodore are two different things. The representation of fragments is organized and held together momentarily for the resulting photograph, constructed within the “real” space of my studio. The absent character in the studio, with a literal stand-in of the repeated lens, is myself.

Well certainly there are many layers within that configuration—it’s really fascinating to think that continuing to follow your practice over the course of time, one may likely find out new things about works from years ago!

In conclusion, how do you see your work developing as you continue within this framework and also as you complete your graduate studies?

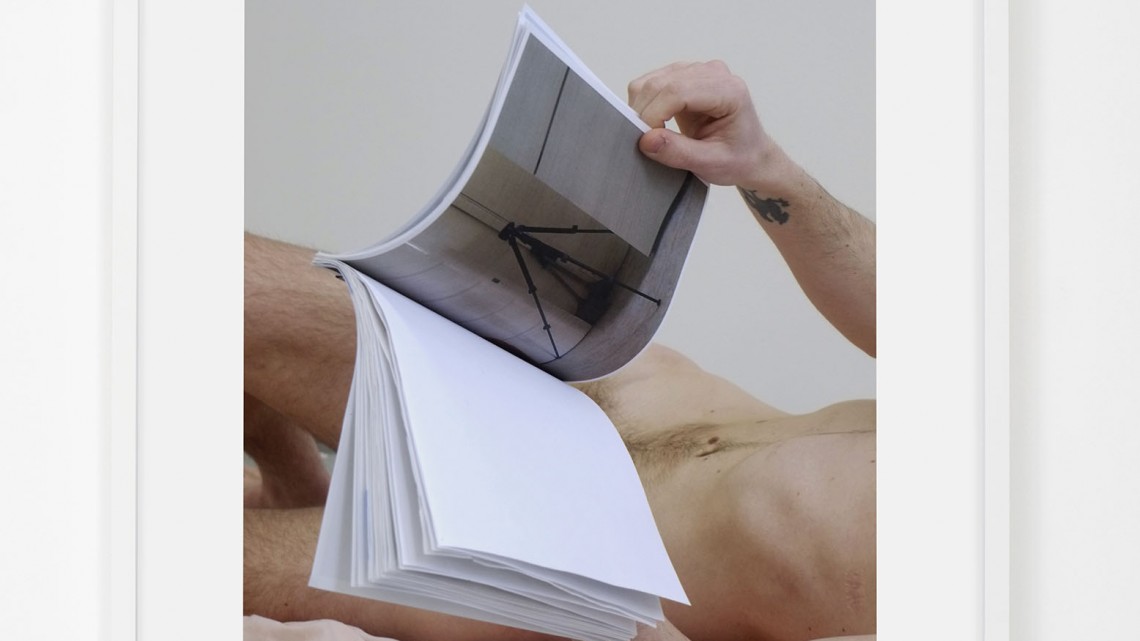

This is a tough one! I’ve been thinking a lot about what’s necessary to depict in the pictures I’m presenting: How much of the investment in portraiture is in the conditions for the making of the picture vs. the content depicted? I’m beginning to physically cut out the subjects, leaving only the margins. In a studio visit with a friend a few days ago we talked about the difference between a picture depicting a performative gesture or arrangement versus an object that performs that same gesture with the viewer, over and over again. The work I’m focusing on developing towards my thesis is keeping this in mind.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Study for Roses at night, for K., 2006 – 15, 2015