João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva: One month without filming

July 11 – September 20, 2015

REDCAT

631 West 2nd Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012

Going to the movies is one of the city dweller’s best hopes for ducking the heat in summer, and so it is that João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva’s exhibition at REDCAT appears as a kind of oasis. Upon entering the darkened gallery, one finds nine whirring film projectors looping obscure epiphanies in dusky light. Each of these 16mm films is silent, and most slow movement to such a crawl that even the most taken-for-granted actions are rendered freshly enigmatic (we’re all foreigners to the world of slow motion). The newer pieces were shot during the Portuguese duo’s travels in Japan, though the show’s koan-like title warns against reading the films as narrowly encapsulating experience. Innovators like Muybridge, Marey, and Edgerton photographically grasped otherwise imperceptible intervals of motion in order to prove things about reality (famously, whether a galloping horse has all four feet off the ground at the same time). Gusmão and Paiva do the same to unravel reality’s claims on the medium—and with it, the medium’s attendant obligation to description.

João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva, installation view, REDCAT, Los Angeles, 2015. Photo: Rafael Hernandez.

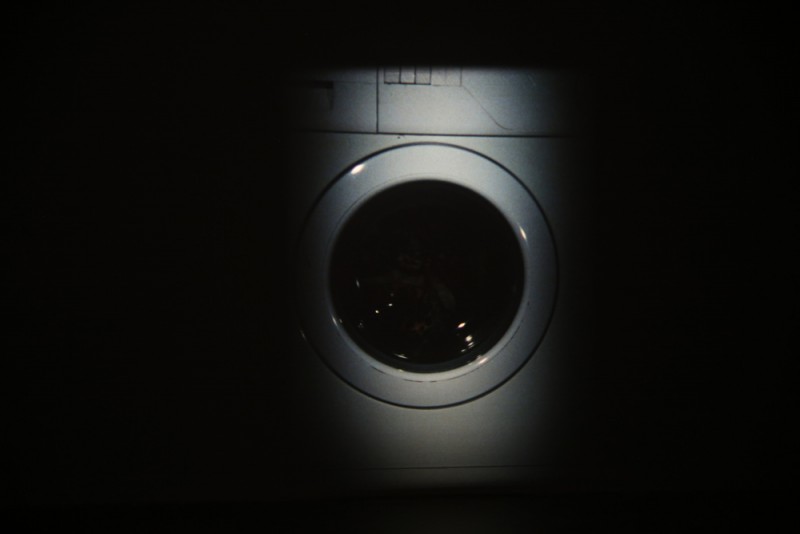

Slow motion is how Hollywood does awe and how sports telecasts clarify disputed calls, but it’s also long been the province of surrealism. That’s where Gusmão and Paiva start: with a film of a washing machine wittily projected at ground level. The camera draws nearer and nearer to the washer’s eye, until this mirror image of the camera lens fills the entire frame. A thick garment in leopard print undulates in mesmerizing waves, curling away from waking reality.

João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva, installation view, REDCAT, Los Angeles, 2015. Photo: Rafael Hernandez.

One presumes this is the same washer that is played for laughs in the essay written by Gusmão to accompany the exhibit (“Pedro, did you manage to get the washing machine going? How the hell do you work this piece of shit?”), but perhaps it is better to say that the text, as chatty and quixotic as the films are sparing and cryptic, parallels the images rather than explains them. Gusmão’s fascinating story of Japanese photographers shooting war planes in Okinawa, for instance, does not really account for the expectant image of onlookers pointing their cameras towards a distant plane as it scrolls across the frame. Even with seemingly ethnographic subjects like workers sleeping on a bullet train (stillness amidst speed, the specter of that which remains hidden in plain sight) or family members cleaning a gravesite (simple movements of sweeping and weed-whacking suffused with a luminosity one associates with religious subjects), the image moves too slowly to be pinned down. “They’d ask what we’d come to film, what issues interested us there,” Gusmão writes of the people the artists encountered in Okinawa. “I’d open my eyes wide and say, well, we’re making a sort of documentary, we’re filming ghosts in slow motion…”

João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva, installation view, REDCAT, Los Angeles, 2015. Photo: Rafael Hernandez.

This attraction to the invisible animates one of the exhibition’s few films to eschew slow motion: One day without filming in Naha City. The camera is posted to the top of a car as it descends into the darkness of a parking garage, resulting in a black frame salted with occasional specks of fluorescent light that are nearly indistinguishable from the dust that invariably collects on the film itself: a communion of medium and subject suggesting the negation of one of the Lumières’ early panoramas—or maybe some discarded b-roll from Walter Hill’s immortal heist flick, The Driver (1978). The piece makes an especially nice fit at REDCAT, given the gallery’s proximity to the parking garage underneath the hard sunlight and architecture of Gehry’s concert hall.

João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva, installation view, REDCAT, Los Angeles, 2015. Photo: Rafael Hernandez.

Another loop at normal speed, Stonefish and round table, stays aboveground. In the first of two shots, a documentary camera attentively follows a butcher’s skillful hands as he selects a deadly stonefish and wields his knife to turn poison into food, the fish’s ugly skin finally coming off as easily as a slipper. A cut finds the camera placed at the center of a revolving lazy Susan as four friends chow down: a wonderfully simple “special effect” that thoroughly boggles perspective while at the same time conveying the bonhomie of a shared meal.

João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva, installation view, REDCAT, Los Angeles, 2015. Photo: Rafael Hernandez.

And yet even at its most exuberant, One month without filming remains paradoxical. The whirligig shot breathlessly outstrips perception, but the camera itself remains immobile, impassive, unmanned. The camera’s automatism boomerangs back upon the intrinsically haunting nature of film installations: the strange fact that for most of the gallery’s waking hours these projections play for no one.