Born in Seattle in 1943, Terry Fox came to San Francisco in the 1960s, and lived and worked between the Bay Area and Europe until he moved permanently to Europe in the early 1970s. Fox was part of the performance, video, sound, and conceptual art movement that defined the period. He created a number of memorable works in public places, as well as at the Berkeley Art Museum and at Tom Marioni’s Museum of Conceptual Art, as well as Reese Palley Gallery and the Richmond Art Center. In 1972, Fox’s video work was accepted into a show in Düsseldorf, Germany, which also included the iconic artist Joseph Beuys. With the help of an NEA grant Fox was awarded, he went to Düsseldorf and performed with Beuys, an experience that he said “changed my interest in the kinds of spaces I wanted to work with.”

This interview was done via phone between San Francisco and Cologne, Belgium, on January 9, 2002. Terry Fox and I edited and completed it with assistance from Marita Loosen-Fox in 2003. Fox passed away in 2008, and Ms. Loosen-Fox agreed to the publication of this interview in 2015. It is with much gratitude for her input and support that it appears here in its original form.

Terry Fox: I have a problem with the word “conceptual.”

Terri Cohn: That’s a good place to start, because my first question is, when did you become a conceptual artist, and why did you become one?

I didn’t even hear the word “conceptual” until much later. It may have been when Tom Marioni opened the Museum of Conceptual Art.

So how did you identify yourself? As a sculptor?

Yes. But I was a painter first. I started seriously painting in 1962. I lived in Rome then. I went there to go to the painting school, but they went on strike and closed so I couldn’t. But I stayed there for a year and painted.

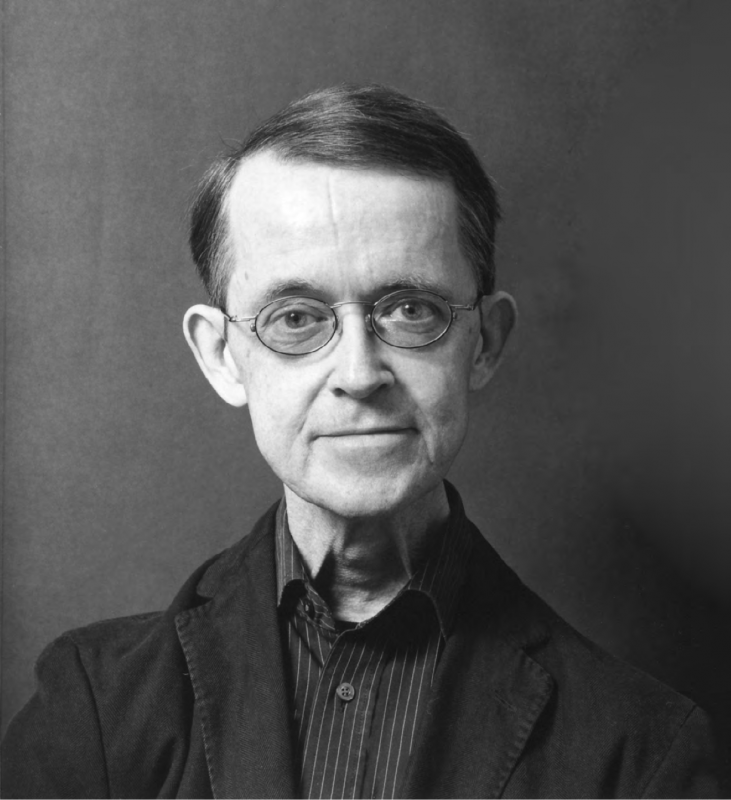

Terry Fox photographed by Peggy Jarrell Kaplan, 2007. Courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, Inc.

From there, did you come back here to the west coast?

Yes. I met my future wife in line at American Express in Rome in 1962. I lived and painted there until 1967. She became a really popular designer—she was designing for Alvin Duskin. She got a job and we had a chance to leave the country, so we moved, first to Amsterdam, and then I spent all of 1968 alone in Paris. That was a really wild time.

Were you doing street performance then?

That’s when I started. Everybody was doing it, and it was strange for me. I did my last drawings in Paris, and they were the only things I brought back with me that was like visual art. Now the Berkeley Art Museum owns two of them, and The Oakland Museum owns two of them. They’re called The Paris Wall Drawings. Those were done in 1968.

Can you tell me a little bit more about them? If that’s the only thing you brought back from Paris, they must have had great meaning to you.

I was trying to represent how the walls looked at that time in Paris. Now everything is cleaned up, but they were very beautiful at that time. I had been doing figurative painting, and I was trying to move away from that, to do something more abstract. Also, something that would cost less money.

Do you mean less money for materials?

Yes.

Being a painter is very expensive.

Yes. And paper was extremely cheap then. So I just bought ink and paper and started making drawings. From my painting experience, which was very conventional, I needed a subject, so I tried to reproduce the Paris walls.

That sounds really interesting. What happened at that point? It’s 1968 and you were in San Francisco again. What did you start doing?

That was actually the last of my visual work. In 1968, the last paintings I was doing were on Plexiglas sheets. They were painted black, totally spray painted black on the back. Then I scratched different colors into the paint with a hypodermic needle. They almost couldn’t be seen. You had to get down on your hands and knees and really follow them. I think that was the beginning, for me, of a performance sort of idea. At the same time, I had gone to New York, and I found the whole collection of Fluxus books, so I knew all about Fluxus and their activities. When I went to Reese Palley Gallery and talked to Carol Lindsley who ran the gallery then, I told her all about Fluxus, and I think that’s why she accepted me!

A number of artists in your group have talked about Carol Lindsley.

She was really wonderful.

Untitled, 1967. Ink on paper. Collection of University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Purchased with the aid of funds from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Can you talk about that a bit more, how you saw and felt that connection between doing those drawings and performance?

Yes. I came from a very small town in Washington, so I didn’t know much about how to draw, and I really didn’t know much about art history. I mean, the only artist whose book I had was Michelangelo. For me, he was a great artist. I wasn’t into contemporary art. I wasn’t reading Artforum or anything like that.

There’s something very pure about the fact that you came to contemporary art yourself, rather than through another artist or set of influences.

Yes, it was like that. So, I moved to San Francisco, and I went through the whole hippie thing, which was also very creative. I lived right across from the Fillmore, and so I went every weekend to the concerts and to the light shows. There was a thing called “The Life-Raft Earth” that was sponsored by Stewart Brand, who made the Whole Earth Catalogue. He made a chain-link fence in a parking lot in Oakland, and people were invited in, and could bring a tent. We had to stay there for seven days without eating anything.

How come?

It was sort of a prediction about the future. The idea that if things kept going the way they were, that’s how it would end up. It was really funny. People would throw food over the side and we would throw it back. Anyway, Robert Frank, the filmmaker, filmed that. After I met him there, I went to New York for a visit. I can’t remember what year that was, maybe 1967. I was there just briefly, and then came back to San Francisco. Then I went to Europe to live, first in Amsterdam. In Amsterdam, I had reconnected with Bill Wiley, and I started a dust exchange with him. I would send dust from a certain metro in Paris, and he would send me dust, and we would write letters to each other also, saying where we got the dust. I took dust from the Louvre, and all kinds of very interesting places in Paris, and he would take dust from places like the San Francisco Museum of Art, or the San Francisco Art Institute, and then the dust I sent him from the Louvre, he would put back in the place where he took the dust, and I would take the dust that he sent and put it in the Louvre.

You were cross-pollinating the dust in the world!

Yes. It lasted a long time, I think eight months or so in 1967.

That’s so interesting because it was invisible work that only the people involved would know about, because you couldn’t see it.

Yes, it was never in any magazines, or gallery shows; there was nothing to show. It was just . . . a dust exchange.

People today would probably be very paranoid because you were introducing spores from one continent to another. But that’s about now, and when you were doing your dust exchange people didn’t worry about anything like that.

No. It was before anthrax. In 1967, I had also brought with me two paintings on glass, I think they were about 1.5 ft. x 1.5 ft., and as an event, I went to Cologne and was in a film showing. While I was there, I deposited these paintings at Gallery Zwirner, which was the best gallery in Cologne. I don’t know what Zwirner did with them. He’s not there anymore.

He didn’t show them?

He wasn’t there when I went there. So I just left the paintings. They were signed on the back, but I don’t know what happened to them. Maybe he sold them. Who knows?

Did you mind that you never knew what happened to them?

No. While I lived in Amsterdam, I dug a hole in the wall of the apartment I was staying in and filled it full of fish, and called the piece Fish Vault. All these things weren’t known. They were private. I did a lot of these things before I started showing in galleries. Like the public theater. Do you know about that?

Why don’t you tell me about it?

I just picked either six or eight places that I liked in San Francisco that would be interesting. I did one piece at Anna Halprin’s workshop. I used to go there once a week. As for the public theater, I made an announcement that said, “Public Theater, Fillmore-McAllister, 8 PM” on a certain date. At that time, Fillmore-McAllister was a very dangerous intersection. You know, I didn’t even go to that performance.

It was the idea that was the important part of it?

Yes. That also came from being in Paris in 1968, the theater in the streets. I was really interested in Artaud at that time, and Grotowski also. I was trying to combine theater and art.

It sounds like it. It also sounds as if you consistently responded to where you were, so when you were in Amsterdam you were responding to that place, or when you were in San Francisco, even though the ideas might be useable in either place, that you responded to the place specifically.

Yes, that’s right. I was responding to the situation of the place. That started very early, this very localized response to wherever I am. It’s still going on.

Is this still 1967?

No, now it’s 1968. At the end of 1968 I moved back to San Francisco. I did a lot of work on Golden Gate Park Beach with free-flying polyethylene sheets, just flying in the wind. Then, in 1969 I had my first show, Summer Symposium, at the Karl Van De Voort Gallery. For that I filled the whole basement floor with polyethylene sheets that were powered by a fan, so they rippled like waves. You couldn’t walk on the floor, but you could stand on the bottom step and look in. Tom Marioni was in the same Summer Symposium show. That’s when I met him.

Performance Sheet, 1969. Polyethylene sheeting, fan. Installation view at

Van De Voort Gallery, San Francisco, 1969. Courtesy of the Terry Fox Archives.

That must have been a significant meeting.

It was for me. Tom was already the curator at the Richmond Art Center. When he invited me in 1969 to be in The Return of Abstract Expressionism, I again used flying sheets. Some were outside being moved by the wind, and some were inside. The next thing Tom did was a sort of radical idea. He had hired Larry Bell to visit a lot of artists and look at their work, and pick out three. Then he invited us to a show in Richmond in the Sculpture Annual that they had every year. That was 1970. That’s when I did my Levitation piece.

Do you want to talk about it a bit?

Sure. At that time I had Hodgkin’s disease, and I had just gone through an operation. I really wanted to get rid of it, and I really did want to levitate. I was given the big major gallery, and I covered the floor with white paper so the walls, the ceiling, and the floor were all white. It was already kind of like . .. floating.

Sort of like a hospital room?

Yes. I lived on Capp Street near Army in San Francisco, and they were just building the freeway there. We rented a truck and took a ton and a half of dirt from there to Richmond, and then I laid the dirt down in a square that was twice my body height on this paper floor. I had polyethylene tubes, and I had some of my blood taken out and I filled a tube with blood and made a circle, like you always see in Leonardo’s drawings. Then I lay on the earth in the circle, but I fasted for three days and nights first, to really empty myself. I had four long polyethylene tubes that were much longer than the one full of blood. One was full of milk, and one was full of urine, one blood, and the fourth water. I held two in each hand, and I lay there by myself for six hours trying to levitate. The door was locked, so it wasn’t a performance that people could see—nobody was allowed in the room. I really felt like I levitated because I lost all the sensation in my body. I wanted to leave the Hodgkin’s behind, and that was a way of doing it.

Did you eventually get rid of the disease?

Yes.

So maybe that helped?

Yes.

It sounds like an amazing experience.

What I was trying to do was to energize that space in such a way that when people came in after I was gone, they could feel the energy. That was the sculptural idea behind the whole thing.

Did the installation stay up for a period of time?

No! But Tom can tell you that story. He got fired because of that. The director, Hayward King, really didn’t like this piece at all, and so he brought in the Fire Department, the Health Department, everybody. Of course the Fire Department immediately tore some of the paper off the floor, and said, “That’s extremely flammable”; the Health Department guy said, “We don’t know where this dirt came from. It could be full of poisons,” and so on. I think that the Bay Area was fairly traditional, and that was pretty “out there” for the time.

What happened after that, Terry?

When he got fired, Tom decided, since he was a curator, to found the Museum of Conceptual Art. We had become really good friends by then, and I needed a studio. He found an office space across the street from Breens Bar, and that was the first Museum of Conceptual Art. It had a small glass cubicle in the front and that was his part, and the big space I covered with white paper, and that was my part. Whenever he did the shows, I would just clear my things away and we would do it in the back, in my space. Then we both moved together across the street, above Breens, and Tom had the second floor and I had the top floor.

That must have been amazing, to have a whole floor.

Yes, because the upper floor was really in ruins. And there was a totally vacant building next to ours that we could go through the window of, and get into what had been a hotel. It was full of their stuff too, so that whole experience was really wonderful.

What kind of work were you doing at that point?

I participated in all the shows that Tom had in the Museum of Conceptual Art, and I did a piece at the de Saisset Museum in Santa Clara.

I know that a number of artists in your group showed at the de Saisset. Tom had driven his car into the museum as a piece. Lydia Modi-Vitale, who was the director at the time, was very interested in conceptual art.

In 1971, there was a show there called Fish, Fox, and Kos, which included Paul Kos, Tom (his pseudonym was Allan Fish), and me. That was another kind of strange experience for me. Again, I did a long fast, and didn’t sleep beforehand.

There seems to be a pattern here, that you spent periods of time either not sleeping or not eating prior to an event.

Yes. This was both. It was still in my mind a way of cleansing my body, of cleansing all this disease out. So I bought two live fish in Chinatown, big bass. I used cords and tied one to my tongue and one to my penis. Then I sat up until they died, which was really a long time. I thought it would be like twenty minutes, but it was at least two hours. I thought they’d be dead and then suddenly I’d see the tail flip a little bit and I could feel the vibrations really strongly through the cords. With that, and passing whatever I had to them I hoped they could take it and die with it.

I had covered the floor in the museum with a white tarp. About three feet off of the floor, I made a roofing of white tarp over the whole space and I brought the sheets. I retied the fish, and just lay down and then I immediately went to sleep. There was an opening and people could look through the door but not come in the space. So they saw me sleeping with these fish tied to me.

It must have been exhausting too to do that!

No! It was very relaxing. It was nice to sleep, because I hadn’t slept for so long. I slept through the whole opening. They had to come and wake me up and say it was over.

Your actions seem to have so much personal significance and symbolism connected to them. But you also have a sense of humor, somehow, about your work. Most artists wouldn’t dream of sleeping through an opening. Everybody is so involved with their own self-importance. There’s something refreshing about that. It’s wonderful that you left those paintings at that gallery in Cologne, and you didn’t know whatever happened to them; it didn’t matter. It was the act of doing it that was important.

Yes, and it was the most important gallery in Cologne.

How long did you stay in San Francisco at that point until you left again?

I left in 1972.

So you only stayed for a few years?

No, I was there from 1962 to 1967.

Did you feel that there was support for doing the type of work you were doing in San Francisco?

At first there wasn’t; that’s why Tom had to open his own museum. But then people like Carol Lindsley, who was working at Reese Palley Gallery in 1970, let me use objects and paintings and do performances. But the performances also were private . . . actions like asbestos tracking, and pushing the wall as hard as I could. There was a big dip in the concrete floor of the space, so I filled that full of water, and made kind of a huge pond there.

In the gallery?

Yes, a reflecting pond.

It must have been beautiful.

It was. Reese Palley was a really great gallery. They weren’t so much into sales, because Reese Palley himself sold porcelain birds. That’s how he made his money.

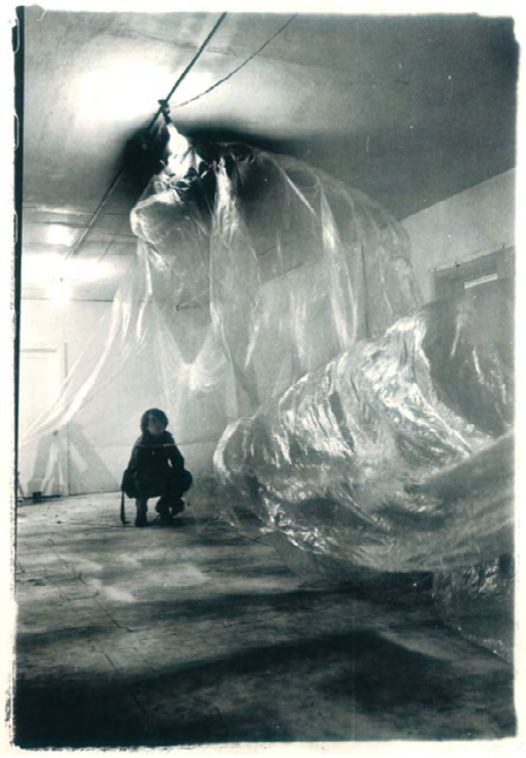

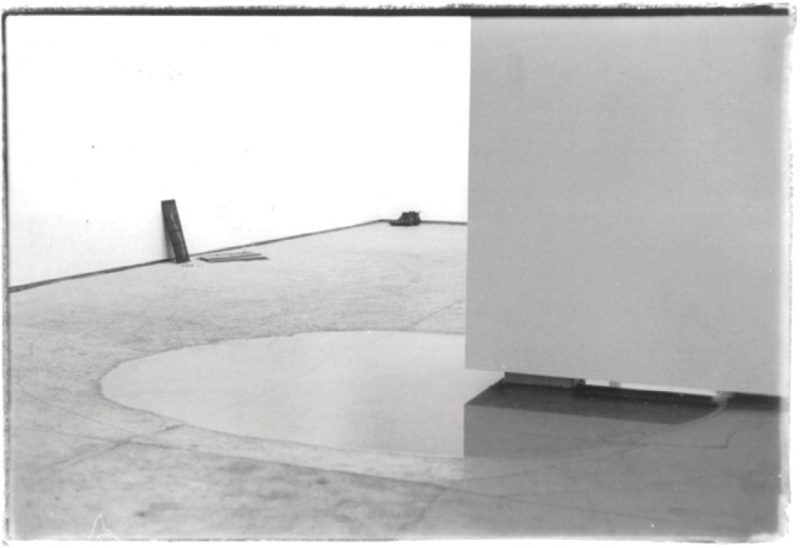

Evaporated, 1970. 25 gallons of water. Installation view at Gallery Reese Palley, San Francisco, 1970. Courtesy of the Terry Fox Archives.

So he could be committed to doing more avant-garde things because he had another source of income?

Yes, that’s right.

Are you still doing the kind of work now that you were doing then?

Sort of. I mean, things change.

Of course. It seems you also had a very strong interest in the link between art and life in your work, and in connecting sound and space.

I did change to working more with sound. Also, in 1972 I got an NEA grant, so I bought a camera and started making videos. That really opened a big path for me because I could send videos to shows. So I started being in shows that weren’t in San Francisco. There was a show in Dusseldorf, Prospect ‘71 Projections, and it included one of my favorite artists, Joseph Beuys. They paid for my trip to go there, but my main purpose was to meet Beuys. I also wanted to do a performance somewhere. So I went to the Art Academy and I met him. He was really wonderful. His wife and children were gone, so he drove me to his house and made dinner and we talked. He said I could do my performance in the basement of the Art Academy. He arranged to have the poster made; it was really nice. Then he talked to me about a week before, and asked if he could do the performance with me. It was totally incredible for me!

The reason he wanted to do the performance with me was, he had a mouse that lived under his bed and this mouse had just died. I know, the story doesn’t sound believable at all, but it’s true. Anyway, this mouse had died, and Beuys wanted to do a kind of funeral for it. When he asked if he could do it, of course I was thrilled. So both of our names were on the announcement card and poster for Isolation Unit. They were put up on the walls all around in Dusseldorf. He had just made his Block Edition Felt Suit and he wore it for the first time to this performance. He had a reel-to-reel tape recorder and he gave the mouse a ride on the reels as it was going. We recorded the whole thing. I had long iron pipes that I banged together, because I was already as interested in sound as in performance; I was changing a little bit, always including sound in my work. I had a window with six panes in the corner and I tried to break the glass with the vibrations from the pipes. When I felt like it was almost breaking, I’d smash the glass with the pipes. I had a candle in the middle of the space with a light bulb hanging right next to it, so you couldn’t see the light from the candle except very close up.

Because the light bulb would block the candlelight out?

Yes, that’s right. Then with the two smallest pipes—they were maybe a foot long—at the end of the performance I sat and tried to bend the candle flame with their vibrations. That did work. Beuys walked around holding his hand open, showing the dead mouse to the public, who were behind a rope at the entrance. They couldn’t come into the room. It was a real dirty room. It was a former coal bin in the bottom of the Academy.

It sounds like quite a contrast to all the pristine white spaces you usually work in.

It was exactly the opposite. After doing that, I changed my interest in the kinds of spaces I wanted to work in, too. I didn’t even think about that until you mentioned the white spaces.

What kind of spaces did you decide to work in after that?

Oh, interesting spaces! That performance helped me a lot, because we also made a record, and then afterwards Lucio Amelio, who ran a gallery in Naples, came to buy some work from Beuys. He was looking through a stack of papers and Beuys said, “Oh this is a great artist. You should give him a show.” Lucio couldn’t say no because he wanted Beuys’s drawings. So he said I could have a show in Naples, and my next show was in Naples at his gallery. It just went on from there. I met more and more people, and I really liked Europe anyway. I was in Documenta in 1972.

So it sounds like it was a natural progression for you to eventually just stay in Europe and to not come back here.

Yes, I still like it better.

Is that how you ended up moving to Germany?

No, I lived in Italy for 7 or 8 years. The last place was Florence. But at the same time I was taking train trips and showing in Vienna and Düsseldorf and in shows like Documenta. So I started to meet more and more people. I had a show in Eindhoven at Paul Panhuysen’s space at Het Apollohuis. At that time, I was losing my apartment in Florence, and he told me about Liège, and that his friend Arnold Dreyblatt, who is a sound artist, had just moved there. So I went, and there just happened to be a house available right next to Arnold’s. I rented it and then the people from Eindhoven had a truck and I went back to Florence, packed all my stuff and put it in their truck and we drove to Belgium. I lived in Belgium until I moved to Cologne in 1996.

Have you liked living there?

Yes, I like it. When I was still living in Belgium, Marita Loosen, who worked for the television station in Cologne, organized a big sound festival. She came there on the recommendation of Julius, a German sound artist, and invited me to be in it. We met and we fell in love, and we’re still together.