Robert Arneson: Guardians of the Secret II

Brian Gross Fine Arts

248 Utah Street San Francisco, CA 94103

March 12-May 7, 2016

When Bob Arneson began teaching at the University of California, Davis, in 1962, it was not in the art department containing a fledgling ceramics component, which he later expanded into a major artistic hub, but rather in the design department of the College of Agriculture. At the time, the ceramic arts weren’t even poor stepchildren to the Fine Arts—they were bastards expelled, shuffled off to the Decorative Arts wing, their practitioners congregated in Pottery Associations. Arneson studied at Oakland’s California College of Arts and Crafts. Today, the school has been renamed the California College of the Arts, the newer appellation encapsulating the dramatic transformation the notion of craft has undergone over the past 50 years. ”Potters” are now “ceramic sculptors,” and can be found in any significant collection of contemporary art.

All this began to change when Peter Voulkos left Montana and went to teach at Black Mountain College in 1953. Rubbing up against the movers and shakers of abstract expressionism, Voulkos turned the traditionally staid ceramic arts on its head, poking and prodding surfaces into non-functional works of abstracted sculptural art. Relocating to the West Coast, first Los Angeles, later settling in at the University of California, Berkeley, Voulkos influenced a slew of clay slingers, including Arneson. Arneson in turn became an inspiration to his students at Davis—Richard Shaw, David Gilhooly, Bruce Nauman, and Stephen Kaltenbach, among them.

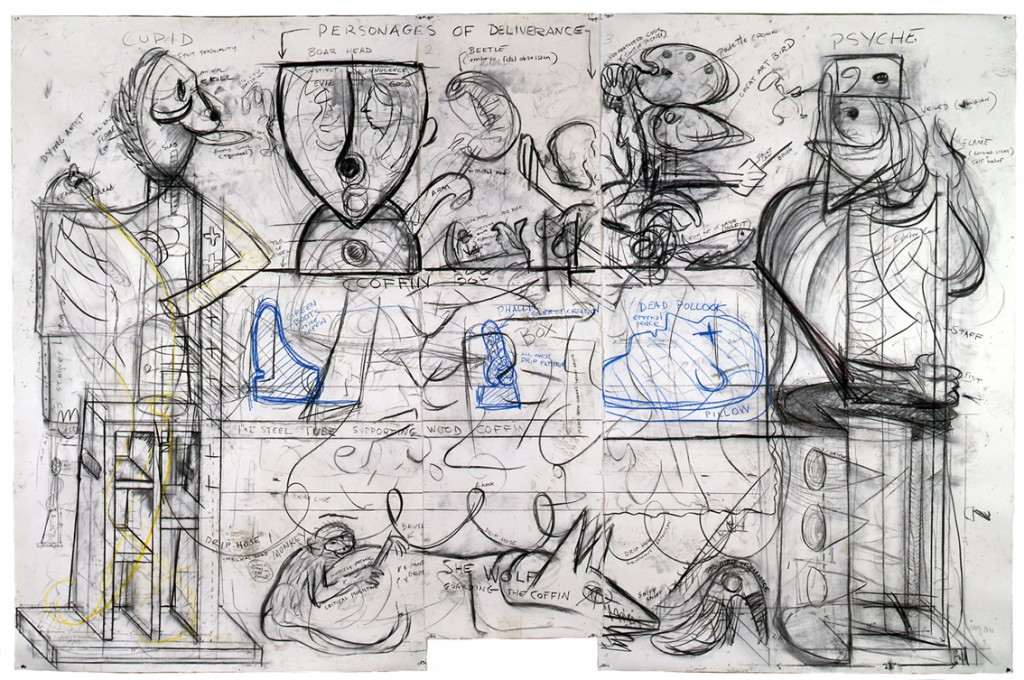

Robert Arneson, Working drawing for Guardians of the Secret II, 1990. Charcoal, oil stick on paper, 84 x 128 3/8 inches.

Arneson later recounted, “What was quite unique in what I was trying to teach was certainly a mild revolution. We have to keep in mind that ceramics traditionally taught in the West, in America, had been in the decorative arts and crafts category. My concern, my purpose certainly as a teacher, was to treat ceramics as another art process. This meant that we had to deal with ideas and content, and I’m not concerned with forms and processes in the craft tradition.”[1]

But as late as 1981, when Arneson was shown with five other like-minded California ceramic sculptors in the Whitney Museum exhibition, Ceramic Sculpture: Six Artists, there was a backlash, with New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer singling out Arneson as dominated, “by a gruesome combination of bluster, facetiousness and exhibitionism – plac[ing] a fatal limit on what his gifts allow him to accomplish, or even to conceive. It is, I’m afraid, the sensibility of a provincial whose outlook has been decisively shaped by the art department gags of the university campus.”[2]

“In the end, it is not the problems and potentialities of ceramic sculpture that we are left reflecting upon in this exhibition—after all, Mary Frank has already showed us what can be accomplished in this medium when it is animated by the requisite vision—but something else. We are left brooding about the thinness and the spiritual impoverishment of the cultural life that has sustained this movement. We are left, in short, with some dark thoughts about the fate of high art in the California sun.”[3]

By dragging the work of Mary Frank into the mix, Kramer only accentuates his own provincialism, and that of New Yorkers in general. If it doesn’t originate in New York it doesn’t exist, and if it does, only as a poor copy. More and more, this viewpoint is being challenged. New York intellectuals believed the Japanese Gutai movement was a poor relation to abstract expressionism and happenings. New York conceptual artists shuffled Yves Klein to the sidelines during his one and only visit to New York. Unfortunately, all too many artists take the bait, and think that if they make it anywhere—it has to be New York. California sculptural ceramics took the wind out of those sails.

Robert Arneson, Guardians of the Secret II (Front View), 1989-1990. Glazed ceramic, wood, plexiglass, steel, canvas, epoxy, and mixed media, 86 x 119 x 26 inches.

The truth is, Voulkos, Arneson and their circle of California mudslingers, created a revolution in the ceramic arts field that continues to reverberate well beyond Kramer’s faded diatribe. The quality of artists that stormed the barricades; Robert Arneson, a, Peter Voulkos, among them; make it clear that something new transpired, that it happened here in California, and their voice was that of the future.

Arneson’s reaction to Kramer was direct. The following year he created the work, California Artist, mocking the critic’s critique. Arneson would not be deterred by the cock-sure intellectual, all too proud of his self-anointed status.

“Innocence is bliss. God, I love innocence. One is free. The more one knows the more one can’t do. And that has always been my background. I think I was basically innocent all along the line. In ceramics, you are not an artist so you are really innocent and you are out of it so you can do anything that you want to do. And you are free to explore in that sense.”[4]

Arneson expanded upon this in an incisive essay published in Ceramics Monthly. “I don’t follow fashion. I try to get below it. If people like what you’re doing, you’re in trouble. You’ve got to keep it edgy, keep pushing until it’s not quite likable, until it’s troublesome—particularly troublesome to the artist. I can remember when my early works were so troubling that I just could not get them out of my mind—they bothered me. Making a toilet sculpture was shocking to me. But it was gutsy, too. It made me realize that I had broken from Voulkos. Before that, everything I did had to be measured in terms of what he was doing, because I was just doing variations on abstract expressionism.”[5]

Robert Arneson, Study for Guardians of the Secret II, 1990. Mixed media on paper, 30 x 44 inches; 38 1/4 x 52 1/8 inches framed

Starting his career in high school as a cartoonist for the local Benicia newspaper, Arneson had no trouble mixing high and low art. This came to the fore in 1963 when he crafted his “troublesome” toilet complete with excrement.

“I had finally made Bob Arneson. I had finally arrived at a piece of work that stood firmly on its ground. It was vulgar, I was vulgar, I was not sophisticated, I was a vulgar person. And if you’re not sophisticated, you’re vulgar. You better be very real about that. But it was also, more significantly, a very important piece…That was the ultimate ceramic, and that was all about our Western civilization. It was also about all the symbolism and verbiage that one would put into what later became Pop Art at the same time, notions and sub-notions, subconscious and conscious, about our heritage. God, I felt good about that.”[6]

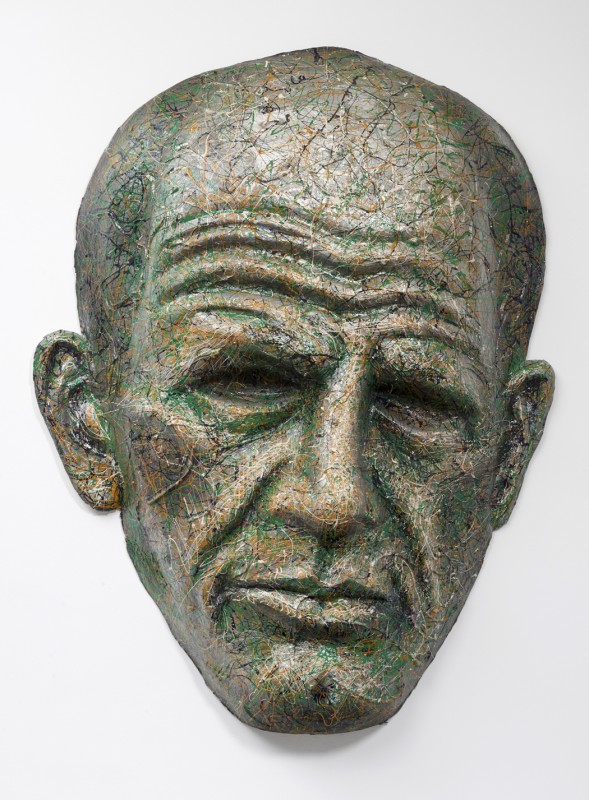

Arneson could be vulgar, but he was serious about his commitment to art. Born in 1930, he came of age at the height of abstract expressionism during the reign of Jackson Pollock. Arneson worked in series, and in the last decade of his life (he passed away at age 62 from cancer in 1992), he completed a series of works on Pollock, from portraiture to replication of his works.

Currently on view at Brian Gross Fine Art, Guardians of the Secret II, the exhibition features the flagship installation work, nine key study works, including working drawings and maquettes, as well as a cast paper wall relief portrait of Pollock and a large-scale ceramic head of Pollock.

Robert Arneson, Stringhalt J, 1987. Cast paper with paint, 53 x 45 x 12 inches.

In the Ceramics Monthly article written after he completed the project, Arneson wrote that, “’Guardians’ has so much going on that I am willing to call it my masterpiece…I chose Jackson Pollock as my role model, obviously because of a strong attraction to his work. I initially started by doing just a portrait of Pollock, like I’ve done with a number of artists over the past 10 or 20 years. In a sense, that was another self-portrait, of course. When we do another artist, we are really doing ourselves.”[7]

Arneson completed 97 works devoted to Pollock between the years 1982 and 1990. The centerpiece for this exploration was Pollock’s work, Guardians of the Secret (1943), in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which Arneson had ample occasion to view on multiple visits to the Museum. Arneson translates Pollock’s painting into a three-dimensional ceramic tour de force, certainly one of his greatest works. God knows why this monumental work is not ensconced in a prominent position in one of the country’s great museums—more specifically SFMOMA—whose acquisition of the work seems proper, fitting, and overdue.

But here it is in all its glory, standing proud in the gallery. Arneson has not only transformed the abstracted painting into glazed stoneware, steel, wood, canvas, rubber and plastic additions, but incorporates a cenotaph, or coffin, in the rear of the work, as a reliquary to the departed artist, complete with death mask, penis, and work boots. It’s a complicated work, so it is with great satisfaction that the gallery commissioned local poet/art historian/educator Bill Berkson to explicate the work in an essay issued in a handsome brochure.

Robert Arneson, Guardians of the Secret II (Detail), 1989-1990. Glazed ceramic, wood, plexiglass, steel, canvas, epoxy, and mixed media, 86 x 119 x 26 inches. Photo by John Held, Jr.

Great as the central work is—and it is a monumental work—the drawings used as studies for Guardians of the Secret II, are equally as compelling. As important a ceramic artist as he is, there is not enough attention paid to Arneson’s drawings and paintings. Nobody in the clay world pays more attention to tactile detail as Arneson, and this translates to his two-dimensional works, as well. I am not schooled enough in the artist’s exhibition history to know if there has been an extensive exhibition of his drawings and paintings, but if there hasn’t, there should be.

There should also be more exhibitions gathering the major players of West Coast figurative ceramics, as well. In the long run, the work of these artists may well supersede the attention given to the Bay Area abstract figurative painters of the era, for they not only leave us with equally superlative works, but in the process upended the notion of craft. And it originated and flowed from here, not from New Yorkers, who were too insular and caught up in their own sophistication to understand that low could be high, high could be low, and that sometimes the “gags” of an outlying art department may portend the future.

—

[1] Oral history interview with Robert Arneson, 1981 August 14-15, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[2] Hilton Kramer. “Ceramic Sculpture and the Taste of California, ”New York Times, December 20, 1981.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Oral history interview with Robert Arneson, 1981 August 14-15, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[5] Robert Arneson, “The Spirit of the Work,” Ceramics Monthly, April 1991, 54.

[6] Oral history interview with Robert Arneson, 1981 August 14-15, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[7] Robert Arneson, “The Spirit of the Work,” Ceramics Monthly, April 1991, 52.